O

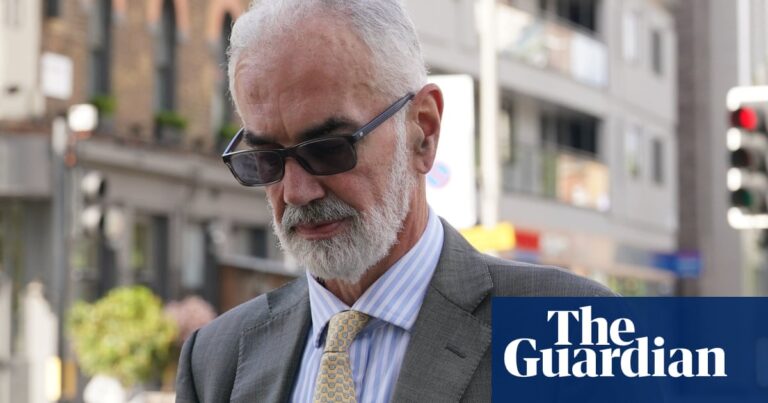

During her four-decade career creating impactful documentaries in the Czech Republic, Helena Třeštíková has achieved a notable feat that has not received much recognition outside her home country. She may very well be the only filmmaker in global cinema who was victimized by her own main character.

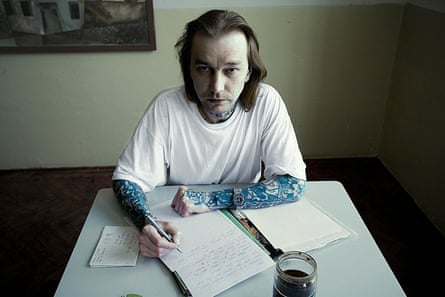

In 1992, while filming her well-known extended “time-lapse documentaries” featuring juvenile delinquent René Plášil, she had to go on a business trip to Germany. As a result, she sent her husband and two children to the countryside for the weekend. However, René discovered that the apartment was unoccupied, broke through the heavily secured door, and stole all the electronic equipment, a few pieces of vintage furniture, and the children’s savings.

During a video call from Prague, Třeštíková mentions that she could have completed the shooting at that moment and ended things. However, she decided against it because she realized that only someone with a strong personality would do such a thing, and she was intrigued to continue pursuing him.

Pushing through challenges when others would give up is a skill that few possess like the 74-year-old. Making films over an extended period of time is highly praised by critics. Filmmaker Richard Linklater received high praise and multiple awards for his 12-year project, Boyhood, which follows the life of the main character. Other notable examples in this genre include Michael Apted’s Up series, which has tracked 14 British individuals for over 50 years, and the German documentary The Children of Golzow, which has been following the residents of a village in Brandenburg since 1961. However, Třeštíková’s dedication to long-term observational studies is unparalleled. In the past 40 years, she has created over 30 documentaries using this technique, which are now being featured in a retrospective on the streaming platform True Story.

In 2007, she was appointed as the Czech Republic’s culture minister by the film-makers’ union. However, her tenure lasted less than three weeks. Despite this setback, her dedication to her craft remains steadfast. At any given time, she is managing 20 different projects, and securing funding for them is a constant struggle. “The funds are needed immediately, but the results can only be delivered years down the line,” she explains. “As a result, some projects have not been successful. However, I always strive to persevere.”

In 1980, Třeštíková stumbled upon her methodology while addressing concerns from Czechoslovakian authorities about the high divorce rates among newlyweds. At the suggestion of a psychiatrist friend, she followed six pairs of newlyweds over a span of six years, which revealed uncomfortable findings for the regime. Despite facing challenges from the state censor, Třeštíková’s Marriage Stories was ultimately approved as a six-part series and caused quite a stir.

The speaker explains that under Communist rule, television movies were heavily influenced by ideology and often depicted romanticized portraits of socialist workers. However, one film stood out as it portrayed ordinary lives without any added dramatic elements, which was seen as quite remarkable.

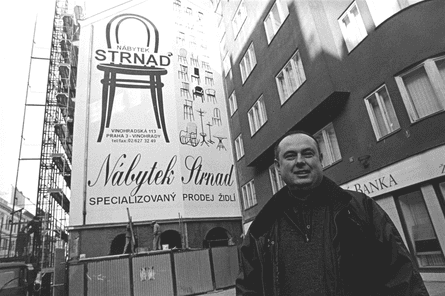

Třeštíková’s films are able to capture drama in seemingly ordinary life stories due to her keen attention to detail. In the documentary Marriage Stories, one of the six couples, Ivana and Václav, stand out as dynamic architecture students who creatively make the most out of their small apartment in the midst of a housing crisis. While Václav creates architectural drawings, their toddler plays under his table and Ivana embroiders in the kitchen. As they open a furniture shop and have four more children, their unwavering smiles never fade. However, after 30 years of marriage and filming, their seemingly perfect life begins to unravel. Their daughter’s wedding is called off, Ivana experiences a breakdown, and their relationship becomes strained to the point of violence and legal intervention. While there is some semblance of a happy ending, its true resolution is uncertain.

According to Třeštíková, the danger involved in her approach to creating films does not lie in the perceived monotony of her characters’ lives. She believes that every life is compelling enough to be turned into a story, a principle long recognized by literature and film. The real risk is that the protagonist’s tale may not be effectively portrayed.

She believes that the most effective method for getting her main characters to speak honestly on camera is to be transparent with them. She compensates interviewees with 1,000 to 2,000 Czech crowns per day of filming (equivalent to £35-70), but she never orchestrates contrived scenarios. Ivana and Václav have conversations in their store or at home; René Plášil is usually interviewed while sitting in cafes, smoking and drinking beer, in the midst of his frequent stints in prison following his time in juvenile detention.

Třeštíková plans questions before conducting interviews, but aims to limit their use during filming. She also involves her subjects in the final editing process of each film. She strives to be a collaborative partner rather than a distant director.

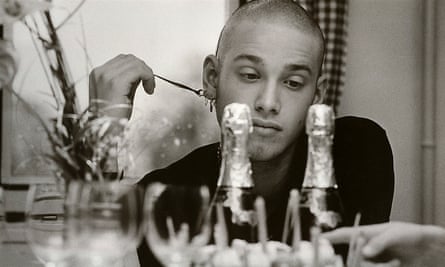

However, even without appearing on camera in her films, it is evident that Třeštíková influences her subjects through her filming. This is particularly noticeable in the case of René, who starts off as her main character and later becomes a robber. As a young man, René had begun to rebel after his parents’ divorce and had initially caught Třeštíková’s attention when she was working on a project about teenage delinquents in the mining town of Libkovice. He stood out due to his determination to go against the system and his ability to reflect on his repeated incarcerations. René expressed himself through memoirs and short stories and impressed Třeštíková with his intelligence and insight into the experiences of prisoners.

Ignore the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

The film they released in 2008 evoked a sense of sympathy. As René navigates his way through a post-Soviet world in the early 90s after being released from prison, Třeštíková weaves together her interviews with him and speeches by Václav Havel, the last president of Czechoslovakia and first leader of the new Czech Republic. Both Havel and René were creative individuals who experienced time behind bars, leading to a feeling that the film is a dual biography: one of a Czech man who becomes a national hero and another who remains trapped in his past.

As the movie continues, Třeštíková also raises doubts about whether René’s struggles are solely caused by the system. She forgives him for breaking into her apartment, but when she lends him a camcorder to film his own scenes and it goes missing, she becomes frustrated. “Why do you constantly ruin things?” she scolds. “I don’t,” he responds weakly. “They ruin themselves.”

After releasing her initial documentary about René’s life, her latest film continues his story. The title, “René: Prisoner of Freedom,” may suggest a pessimistic tone, but the first film’s success brings him newfound fame and alters his life. René’s personal writings are published and serve as inspiration for a graphic novel. Despite returning to prison, he now has a following of young women who admire his writing and eagerly await his release.

After these meetings, relationships typically do not endure for long. However, the movie concludes with the idea that Třeštíková’s project has provided René’s life with a direction and meaning it may not have otherwise had. In the last scene, following the end of another potentially successful romance, he compares his own story to that of Sisyphus, continuously pushing a rock up a hill only to watch it fall back down. “But he carries on with determination, fulfilling his fate with composure,” René reflects. “And by embracing his fate, he becomes more powerful than the boulder.”

Source: theguardian.com