I

In 1958, a 17-year-old named Rose Dugdale was among the 1,400 young women who curtsied before Queen Elizabeth II at the grand debutante event of the summer. This marked the end of a 200-year-old tradition where the daughters of the most elite and wealthy families in the country were presented to the monarch. Princess Margaret, known for her haughty demeanor, commented that the event had to be stopped as it was becoming too accessible for commoners.

The independent Dugdale saw being presented to the queen as a strategic move. She only agreed to do so if her parents would allow her to attend St Anne’s College, Oxford – a women’s college where she would study philosophy, politics, and economics. Looking back sixty years later, she would describe the debutante season as a “terrible marriage market” where young women were objectified and sold. By this time, she had come a long way from her privileged upbringing in rural Devon and London. A recent biography of her, titled Heiress, Rebel, Vigilante, Bomber, perfectly captures the extraordinary journey of her tumultuous life.

The book, written by Irish author and journalist Sean O’Driscoll, recounts the unexpected transformation of Dugdale from a reluctant debutante to a dedicated IRA member. Her daring exploits and devotion to violent republicanism garnered global attention. In January 1974, she participated in the armed hijacking of a helicopter, from which explosive-filled milk churns were dropped on an RUC base in Northern Ireland. Just a few months later, she orchestrated and led a bold art heist in County Wicklow, where 19 valuable works were stolen, including paintings by Rubens, Goya, and Vermeer. These works were then held ransom in exchange for the release of IRA prisoners.

Dugdale was once the most sought-after terrorist in Britain and Ireland, causing a sense of both fear and intrigue in the tabloids. Upon her apprehension, she was convicted and given a nine-year prison sentence after openly admitting her “proud and unyielding” culpability for actions against the government. During the trial, she referred to Britain as “the despicable enemy” and made a defiant fist salute to those watching in the gallery.

O’Driscoll’s book uncovers new information about Dugdale’s involvement with the IRA after her release from prison. She and her partner, Jim Monaghan, developed various deadly homemade bombs, including the well-known “biscuit launcher”. These devices were made from everyday objects and were used by the IRA in rural South Armagh and in west Belfast.

The duo also developed a highly potent explosive which was utilized to cause an explosion at the heavily fortified Glenanne barracks in May 1991, resulting in the deaths of three soldiers and serious injuries to eleven others. The following year, the same explosive was used in a bomb that destroyed the Baltic Exchange and nearby structures in London, resulting in the deaths of three individuals and causing extensive damage worth an estimated £800 million. According to O’Driscoll, “Although Rose Dugdale did not directly cause any deaths, she played a significant role in the loss of many lives.”

O’Driscoll performed interviews with Dugdale, who is now living in a care home in Dublin, as part of his research. The home is run by the Poor Servants of the Mother of God, and Dugdale, who is not a retired nun, is one of the few residents. The resulting book delves into Dugdale’s life, with O’Driscoll speaking to her accomplices and her son, Ruairi, who was born while she was serving time in Limerick prison. However, the book does not provide a complete explanation for why someone from a privileged, English background with a charismatic and fiercely intelligent nature, who even wrote her master’s thesis on Wittgenstein, became so fervently involved in Irish republican violence.

O’Driscoll believes that the time period in which she reached maturity played a role in her actions. It is challenging to distinguish her beliefs from those of other revolutionary organizations that were prominent in the late 1960s and early 70s, such as the Baader-Meinhof in Germany or the Red Brigades in Italy. However, there is a larger question surrounding why she felt the need to go to extreme measures to assert her radical beliefs. This answer likely lies in her personal psychology, which is a complex and nuanced aspect.

A recently released film, entitled Baltimore, focuses on the character of Dugdale and her involvement in the IRA’s raid of Russborough House in County Wicklow in 1974. Though the title references a village in County Cork rather than the American city, the film offers a psychological portrait of Dugdale through her actions during the raid. Imogen Poots portrays Dugdale as a dedicated but tormented person, plagued by paranoia and nightmares. However, the film’s slow pace does not fully capture her passionate and impulsive nature, instead choosing to prioritize atmosphere and implication over delving deeper into her political motives.

Christine Molloy and Joe Lawlor, the co-directors of the film, have always been intrigued by the inner lives of their characters. They were specifically drawn to Rose Dugdale because they believed her to be a reflective and deliberate thinker. Dugdale also had a desire to reinvent herself and adopt a new identity.

The second half of the movie focuses on Dugdale’s 10-day stay in a cottage in a secluded area of west Cork with the stolen paintings before she was caught. The film suggests that this time alone, pregnant, and possibly in a vulnerable state, may have been a unique opportunity for contemplation for a woman known for her impulsive and dangerous lifestyle.

Display the image in full screen mode.

Molloy suggests that there was a prolonged period in which the woman had only her thoughts to keep her company. This period was focused on her personal journey, rather than the details of the art theft or the ransom demands. During this time, she took actions that would ultimately separate her from her old life, including her family, her home, and her birthplace.

Despite receiving criticism, Dugdale has shown no signs of remorse or regret for her actions, as evident in her interviews and ongoing dedication to her cause. Unsurprisingly, the film has faced backlash for portraying a terrorist, especially one from a privileged English background. A recent article in The Mail on Sunday questioned the motivation behind glorifying Dugdale, a high-class woman from Devon who used a helicopter to drop bombs on an army base for the IRA. The Daily Mail’s film critic described Baltimore as a “risky film” that attempts to make Dugdale a relatable character rather than glamorizing her.

I had difficulty with the fact that the intricate portrayal of the main character in the film ultimately caused confusion rather than insight. The film raises important questions about the consequences of her unwavering dedication to violence, but fails to fully address them.

B

Rose Dugdale was born in March 1941 on her father’s 600-acre estate in Devon, known as Yarty. Her Irish name was not commonly used and was replaced with a more English name. The family spent their time between Devon and London, where they possessed a spacious home in Chelsea. Rose’s father, Col Eric Dugdale, worked as an underwriter at Lloyd’s of London while her mother, Carol, studied at the Slade School of Art and was good friends with the author Rebecca West.

Interestingly, Carol Dugdale was previously married to John Mosley, a stockbroker and the younger brother of Oswald Mosley, the notorious leader of the British fascist movement. During an interview for the Irish television series Mná an IRA (Women of the IRA), Dugdale shared that her parents were very attentive and her childhood was filled with activities like horseback riding, sports, fishing, and hunting.

In an article published by the Oldie, journalist Virginia Ironside shares her experience attending the same school as Dugdale in Kensington. She reflects on the teachers, whom she remembers as “oddballs with no formal training.” However, Ironside’s perspective on Dugdale’s upbringing differs from what Dugdale herself has said. Ironside describes it as steeped in “stultifying conventionality,” and recalls how Dugdale and her sister were made to wear formal attire and white gloves for dinner every evening. She also mentions that they were expected to curtsey to all visitors in their home, as per their mother’s request.

Ironside recalls Dugdale in her youth as being awkward and having a more masculine appearance, describing her as a tall girl with a deep voice. She wasn’t conventionally beautiful, but her energy, positivity, intelligence, generosity, and even kindness made her instantly appealing. Ironside even confesses to having a secret crush on her, a feeling that was shared by many other students. It was clear even then that Dugdale was bisexual.

During his time at Oxford, Dugdale engaged in a fervent romantic involvement with a female tutor named Peter Ady. Ady had previously been in a relationship with Iris Murdoch, a tutor in politics at the college. After Dugdale found himself imprisoned in Limerick, Murdoch, now a renowned philosopher and novelist, sent a letter to the Irish ambassador, asking that her former student be given the opportunity to study serious and scholarly material. She explained that Dugdale was an intellectual person who longed to study, but was unable to do so – a cruel additional punishment.

Dugdale became politically involved with leftist ideologies during her time at Oxford University, where she also gained attention in the press. In 1961, with the help of another student named Jenny Grove, she attended a male-only debate at the Oxford Union by disguising themselves as men and causing disruptions by shouting and using masculine voices. This act garnered media attention, especially because Dugdale and Grove had informed a journalist and photographer about their plan and had even invited them to capture their transformation at a local hair salon in Oxford. The Daily Express published an article about the incident, titled “Disguised Female Students Gain Access to Male-Only Establishment”.

Having graduated, Dugdale went on to obtain a master’s in philosophy in the US and a PhD in economics at the University of London, before becoming politically active during the turbulent international protests of 1968. By 1971, aged 30, she had made the decision to sell her house in Chelsea and give away her inherited wealth, which O’Driscoll values at “well over £1m today”, to London’s poor and needy. In order to do so, she rented a building in Tottenham and set up a Claimants Union, offering advice and financial handouts. “There were many immigrant families coming into the area,” she told O’Driscoll. “I couldn’t exaggerate how many people were looking for help.”

Dugdale’s attraction to unconventional male revolutionaries such as Eddie Gallagher and Jim Monaghan was a recurring theme throughout her life. She first met Wally Heaton, a self-proclaimed “revolutionary socialist” who had been deeply affected by his experiences in Malaya, at the Tottenham Claimants Union office. Despite his struggles with alcohol, the two began dating and he introduced her to the violent situation in Northern Ireland. In January 1972, Dugdale’s political views were forever changed after witnessing the tragic events of Bloody Sunday in Derry, where 13 unarmed protesters were killed by the Parachute regiment.

Both O’Driscoll and the directors of Baltimore view Bloody Sunday as the crucial turning point in Dugdale’s evolution from a left-wing activist to a violent revolutionary. Lawlor refers to it as a “tipping point” and a defining moment of her militancy, a moment that brought her thoughts into sharp focus. It appears that all of Dugdale’s wild and ruthless actions following this event were driven by her anger and outrage towards this one terrible event.

In June of 1973, Dugdale, at the suggestion of Heaton, and three others, burglarized her family’s home in Devon and stole valuable items such as paintings, antiques, and silver while her parents were away. Dugdale then decided to hide the stolen items at the home of her former lover Peter Ady in Oxford. Ady later informed Dugdale’s parents, leading to a trial. During the trial, Dugdale expressed love for her father but also told him that she despised everything he stood for. She received a suspended sentence of two years, while Heaton, who did not directly participate in the robbery, was given a six-year prison sentence.

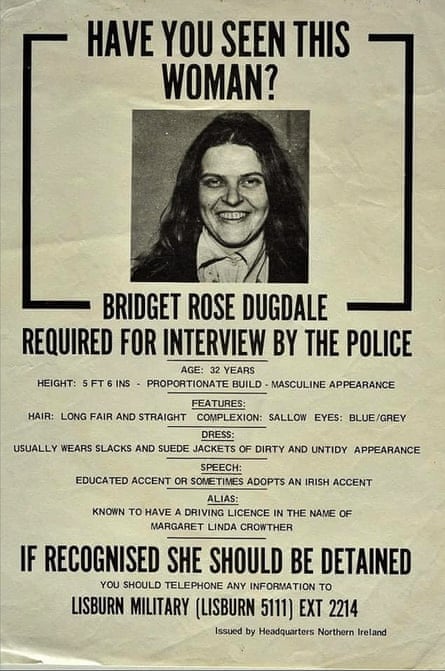

Later that year, she met Eddie Gallagher, a bold member of the IRA who operated independently from the organization’s command. She grew even more devoted to the cause of Irish republicanism and, in January 1974, she and another IRA member hijacked a helicopter in County Donegal and forced the civilian pilot to fly them and their dangerous cargo across the border to Strabane. The bombing attempt resulted in chaos as one bomb was dropped in a river and the other failed to detonate at the barracks. In the aftermath of the attack, a wanted poster of Dugdale with a smug expression was circulated throughout Northern Ireland, describing her as “usually wearing dirty and untidy slacks and suede jackets.”

In April of 1974, the bold duo successfully raided Russborough House for art, but after a country-wide pursuit, Dugdale was caught in a cottage in west Cork with all 19 paintings in the back of her car. She had threatened to burn the paintings if the gang’s demands for the release of IRA prisoners, specifically the convicted Price sisters, were not met. At the time, the Price sisters were on a hunger strike in Brixton prison for their involvement in IRA bombings in England. However, Dugdale’s show of support was partially undermined by a statement from the sisters’ father, Albert, urging her not to destroy the paintings as it would be considered a sin.

Despite being imprisoned and pregnant with Gallagher’s child, Dugdale remained a source of irritation for Irish security forces. On October 3, 1975, she made headlines once again when Gallagher and another IRA member, Marion Coyle, kidnapped Tiede Herrema, a Dutch businessman, from his home in Limerick. They demanded Dugdale’s release in exchange for Herrema’s safety. This kidnapping sparked public protests and was condemned by the IRA, who distanced themselves from the actions of Gallagher and Coyle. The kidnappers and their victim were eventually found in a house in County Kildare, leading to a three-week-long siege. As trained negotiators communicated with Gallagher and Coyle through an upstairs window, snipers were positioned on nearby rooftops. The influx of domestic and foreign media led to villagers renting out their spare rooms and couches.

Display image in full screen mode

After some time, Herrema was set free without any injuries and Gallagher received a 20-year sentence in Portlaoise prison. Coyle, on the other hand, served her term in Limerick prison and bonded with Dugdale. Dugdale later recalled, “Marion had shown her dedication as a volunteer. She was exceptional.” Dugdale eagerly anticipated seeing her in person after months of only seeing her on TV.

After being released from prison, Dugdale became actively involved with an organization called Concerned Parents Against Drugs, which was controversial for its direct and forceful approach to addressing Dublin’s growing heroin issue in the early 1980s. The group enlisted members of the IRA to help in their efforts, marching on the homes of known drug dealers and pressuring them to leave. In O’Driscoll’s book, a woman who watched Dugdale’s son remembers hearing her speak at an anti-drugs rally and feeling grateful that she wasn’t involved in drug dealing or use, as Dugdale’s intense speeches would invoke fear in anyone.

T

Rose Dugdale had a clear belief that her rebellious life was made up of daring and revolutionary acts, all aimed at showing her steadfastness and passion for a cause she wholeheartedly believed in. In order to gain credibility and prove herself, she had to become even more devoted than the most hardened members of the Irish paramilitary she looked up to, despite their skepticism towards her English background and privileged upbringing.

During an interview with Irish TV in 2012, she stated that people from England are always considered British, and based on her background, it was not unexpected that the republican movement had trouble accepting her.

In order to gain acceptance, she had to engage in a lengthy struggle against her own nation, social status, and family background. “I had to confront the notion of taking lives, but ultimately it was the only way to manage them,” she later reflected on the choice that would greatly transform her. “Essentially, it was a military operation that had potential for success. In my mind, there was never any doubt about it.”

According to Sean O’Driscoll, Rose Dugdale’s dedication to her cause resulted in her losing her family, friends, and a privileged and secure life. It also led to the deaths of many others. Despite her old age, Dugdale remains as committed to her cause as ever, with a single-minded focus. O’Driscoll once asked her what her best day in life had been, expecting her to say the day her son was born. However, she surprising replied that it was the day of the Strabane bomb attack. This indicates that it was the turning point for her and there was no going back from that moment.

During his research, he had a memorable experience at the National Army Museum in Chelsea. He was surprised to find a display about the Troubles that included a biscuit launcher developed by Dugdale. Looking out from the museum’s window, he could see Dugdale’s family home – a beautiful house with a park in front and the Duke of York military base next door. This made him question why someone would reject such a privileged upbringing for a life of extreme radicalism. Dugdale’s level of commitment was unquestionable and only added to the enigma that surrounds her.

-

Baltimore will be showing in theaters across the UK and Ireland starting on 22 March.

-

Rose Dugdale, the Heiress, Rebel, Vigilante, and Bomber, led an extraordinary life as depicted in Sean O’Driscoll’s book, published by Penguin for £10.99. To support the Guardian and Observer, order your own copy at guardianbookshop.com. Additional charges for delivery may apply.

Source: theguardian.com