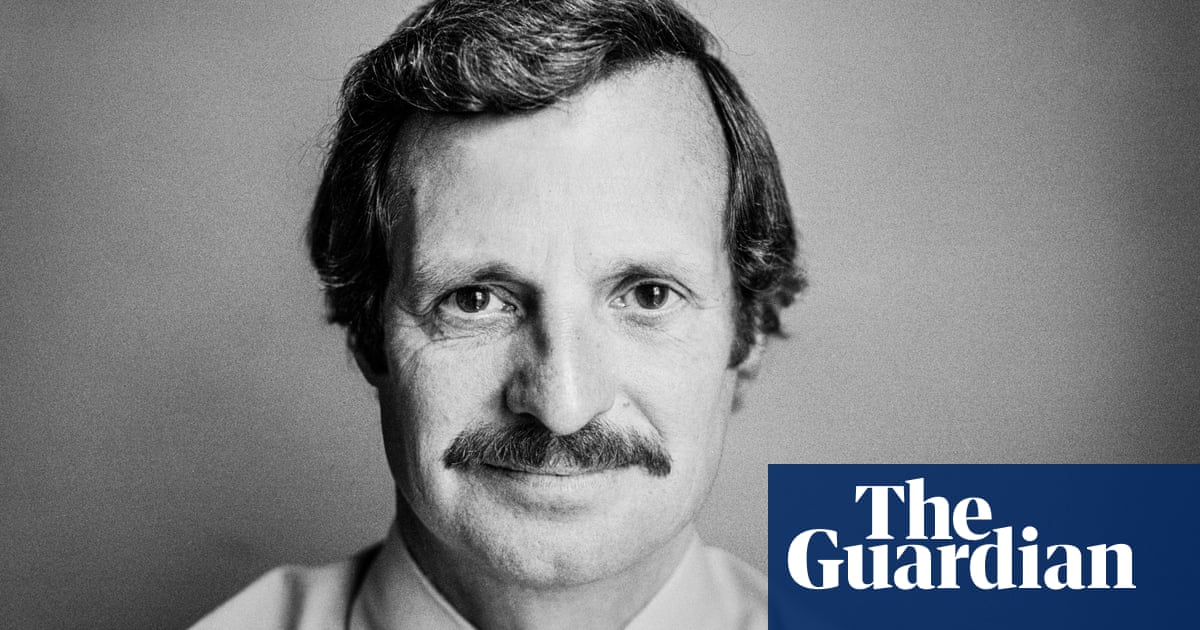

Ronald Atkin, a previous editor for sports at the Observer, was a journalist known for his exceptional standards, whether overseeing the work of other writers or crafting his own pieces, often covering elite tennis or football games. However, he also had a sense of humor and could poke fun at the quirks of his industry, representing the more light-hearted side of the old Fleet Street newspaper community.

In a humorous article published on the Sports Journalists’ Association website in 2012, the author, who had been named their journalist of the year nearly three decades prior, shared some of the ways in which his name had been misspelled throughout his career. Some of the variations included Atkins, Aitken, Atkinson, and Hatchkin, and he had also been referred to as Rod or Tim instead of Ronald. Even in the citation for his top honor in 1984, the SJA had made a mistake in his name.

Ron, who passed away at the age of 92, was known for his accuracy and attention to detail. He served as a tennis correspondent and also wrote about football and cricket for various publications such as the Observer, Sunday Telegraph, and Independent on Sunday. He was also a prolific author, with books on topics ranging from the Mexican Revolution to the Canadian Mounties, the retreat from Dunkirk, and the 1942 Dieppe raid. He even wrote a guide to the world’s best bars, a reflection of his sociable personality, which was common among journalists in the old Fleet Street.

After his first wife, Brenda, passed away in 1982, he remarried Julie Welch, a colleague at the Observer. He had encouraged Welch to become the first female journalist to cover English league football for a national newspaper. In the beginning of her career, as the only woman in the press box, Welch faced numerous instances of sexist behavior, including being grabbed and kissed by Stoke City manager, Tony Waddington.

As the leader of her department, Atkin promptly contacted Waddington with a request for a resolution to the recurring issues they faced in obtaining passes for Stoke’s matches. She also requested that until this matter is resolved, he refrain from giving our reporters preferential treatment.

He was raised in Aspley, a neighborhood in Nottingham, where his parents had jobs in significant local factories. His father, George, was employed at Raleigh, the largest bicycle factory in the world at the time, and his mother, Winnie (nee Truman), was a lacemaker. He completed his education at High Pavement grammar school and at the age of 16, he began working at the Nottingham Evening Post, one of the four daily newspapers in the city.

He followed the traditional path for those with talent and passion, progressing from messenger to copy boy to reporter and then subeditor.

In 1953, he came to Bermuda for the initial of two stints as a journalist for a nearby newspaper. Upon returning to the UK four years later, he accepted occasional editing jobs on Fleet Street and wedded Brenda Burton, a former neighbor in Aspley. Two of her sculptures were selected for display at the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition. After their first child, Tim, was born, the family went back to Bermuda for a brief period before ultimately moving back to Britain with their second son, Mike. Ron secured a position as a downtable sub at the Daily Mail.

After working on Saturdays as a subbing shift for the Observer’s sports desk, he was offered a role as deputy to the sports editor, Clifford Makins. He had the chance to collaborate with renowned writers like Hugh McIlvanney and Arthur Hopcraft, who ultimately became close friends. He also had the chance to write match reports occasionally until he was promoted to sports editor after Makins left in 1972.

He started writing books, mainly focusing on military history. His book about the Mexican revolution from 1910-1920, released in 1969, was a success and allowed him to construct a vacation home on the Costa Brava in Spain for his family.

In 1975, the editor of the Observer, Donald Trelford, made the decision to make a change. Ron was given the option of various writing roles and ultimately chose to become the tennis correspondent. He focused on his passion for the sport and had the chance to cover major tournaments in New York, Paris, Melbourne, and most notably, Wimbledon. This assignment brought him much joy and allowed him to form many new friendships over the following decades. It also gave him the opportunity to ghostwrite the autobiography of Fred Perry, a legendary Wimbledon champion from before World War II.

During a time when reporters and the notable figures they covered frequently shared accommodations and meals, Arthur Ashe, who won the 1975 Wimbledon tournament, took on the role of godfather for Ron’s fourth son, Nick. Ron’s third son, Lucas, already had a famous godfather in Brian Clough, the renowned manager of Nottingham Forest, the team that Ron supported until his passing.

On Saturdays without tennis events, he would often attend and report on football or cricket games, demonstrating his diverse sporting interests.

During his vacation in France in 1994, he found out that he was losing his job at the Observer. He had been offered a position as the tennis correspondent for the Sunday Telegraph and accepted it, along with the redundancy payment. In 2000, he switched to the Independent on Sunday and spent several years as part of a content team, covering tennis, football, and other sports until his time there ended in 2008.

Into his 80s, he persisted in composing daily entries for the Wimbledon programme, indulging in his passion for music (he even managed to catch a performance by Frank Sinatra at Carnegie Hall during one of his trips to New York for the US Open), and immersing himself in the works of his beloved authors such as Paul Theroux, Garrison Keillor, and Robert Harris.

After his passing, he is survived by Julie and his four sons, two from each of his marriages. Julie is the author of The Fleet Street Girls, which was released in 2020.

Source: theguardian.com