During the final moments of the Five Nations match between Wales and France in March 1976 at Cardiff Arms Park, the Welsh team was defending against the aggressive attacks from the French team. However, French wing Jean-François Gourdon managed to break through and found an opening on the touchline near the north stand. Just as Gourdon was about to make a move, Wales’s full-back JPR Williams delivered a powerful shoulder charge that nearly sent him tumbling into the crowd. In a victorious gesture, Williams raised his fist and led Wales to a 19-13 victory, securing their seventh grand slam.

Williams’s tackle may not have been within the rules, but it is a vivid memory for Welsh rugby fans. Another lasting image is a photo of the Bridgend No. 15, covered in blood from being trampled by an All Blacks boot. The 1970s were a time when international rugby was not for the faint of heart, and JPR’s survival was due to not only his immense skill, but also his toughness.

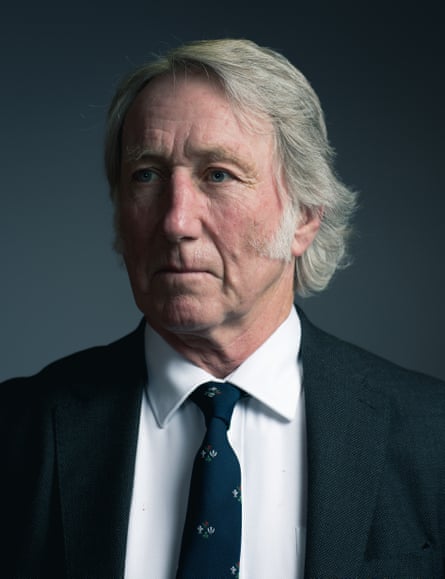

Unfortunately, Williams passed away at the age of 74 due to bacterial meningitis. He will always be remembered as JPR, which are three very meaningful initials in the world of sports. The only player who could possibly contend with him for the title of greatest full-back in history is France’s Serge Blanco. In 1968, when the international board made a rule against kicking the ball directly out of bounds, it opened up opportunities for Williams and other players like Scotland’s Andy Irvine to establish a standard for how an attacking full-back should perform in modern times.

Williams’s renowned toughness may come as a surprise. Unlike many elite players in Wales, he grew up in a well-off, middle-class household. Williams once shared a story of arriving at a Wales Schoolboys’ trial in a Rolls Royce. He saw his upbringing as motivation to show his peers that he was resilient and on their level.

John Peter Rhys was born to Peter and Margaret, who were both doctors, in Bridgend. Margaret was originally from Rochdale, which could have allowed John to potentially play for England, but this topic was not frequently discussed in the Williams household.

It was on the lawns of Wimbledon rather than the muddy fields of Cardiff Arms Park or Bridgend that Williams first made his mark as a sportsman of renown. As a 17-year-old, he won the 1966 British junior tennis title at Wimbledon, beating David Lloyd in the final.

He was gaining a reputation at rugby in Bridgend, where his father was the club president and doctor. By this time Williams had left Bridgend grammar school for Millfield school in Somerset, where future Wales scrum-half Gareth Edwards was a pupil.

After leaving Millfield, Williams moved to St Mary’s hospital in London and spent some time at the London Welsh club. He decided to stick with amateur sports instead of pursuing tennis and focus on his medical education, as his father had warned him that he would not be able to sustain a career as a professional athlete.

As a teenager, he was summoned to join the Wales team for a tour of Argentina in the summer of 1968. There were high hopes for the young player known as John Williams, who made his first appearance for Wales against Scotland at Murrayfield the following February.

Wales acquired a new coach, their previous captain Clive Rowlands. In their 17-3 victory, Barry John, the fly-half, scored the final try. There was a sense of excitement in Wales during the 1970s, which was considered a golden era. With Phil Bennett as Barry John’s successor and JPR joined by JJ Williams and Gerald Davies as the wings, Wales became an unbeatable team in northern hemisphere rugby. At the core of their success was JPR, known for his signature Elvis-inspired sideburns, long hair, and tendency to wear his socks pulled down to his ankles.

His ability to excel in the offensive and defensive aspects of the game solidified his position on the Wales team from his debut in 1969 until his retirement from international rugby in 1981. He further cemented his reputation during the victorious British Lions tours to New Zealand in 1971 and South Africa in 1974, playing in all four Tests for each tour. Williams had previously been a part of a disappointing Wales tour to New Zealand in 1969, where they lost both Tests, so the Lions’ 2-1 series win two years later was a significant achievement.

In Auckland, he sealed the series with a drop-goal from a long distance in the last Test. This caught his teammates off guard, although Bob Hiller from England, who was his backup full-back on the tour, had jokingly told him that he couldn’t truly call himself an international player until he successfully made a drop-goal.

Three years after that, Williams once again showed heroism in South Africa as Willie John McBride’s team triumphed over the Springboks in a series that was often physical and violent. The Lions’ chant of “99” often resulted in full-blown fights, and the image of Williams charging up the field to tackle the much bigger South African lock Moaner van Heerden was a lasting one. However, Williams later admitted that it was not something he was proud of.

Williams earned 55 appearances for the Wales national rugby team, five of which he served as captain during the 1978-1979 season. He was recognized with an appointment to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) in 1977. Amidst his successes with the Lions, he also contributed to the Barbarians’ historic win against the All Blacks at Arms Park in 1973. After concluding his international career, Williams continued to play club rugby for Tondu as a back-rower until the age of 54 in 2003.

In 1973, he wed Scilla (Priscilla) Parkin, whom he had met during his time in medical school. He worked as a trauma and orthopaedic surgeon at the Princess of Wales hospital in Bridgend from 1986 to 2004. Despite rarely joining retired players who became analysts, Williams was always willing to discuss his impressive career, particularly his 11 victories against England.

Scilla and their children, Lauren, Annie, Fran, and Peter, are the ones who continue to live after him.

Source: theguardian.com