At a time of overwhelming entertainment bloat – budget, length, content, discussion – a ride back to the summer of 1994 and the brisk, brilliant economy of Speed feels like the satisfying small-screen vacation we all deserve right now.

Dutch cinematographer turned director Jan de Bont’s breath-stealing action movie hasn’t gained any extra depth or allegorical meaning when rewatched 30 years later (it’s mercifully thinkpiece-proof in its earnest straightforwardness) but it has benefited from a bleak comparison with where Hollywood is at this precarious moment. It’s been a mostly bummer summer at the box office with a panic over expensive big-bet films like The Fall Guy and Furiosa stumbling while the majority who choose streaming instead having to settle for murky, poorly made dreck like Atlas, a much-watched yet much-loathed Netflix night-ruiner. We have a movie star problem both in quantitative and qualitative terms, too few A-listers under 50 still packing ’em in and those who somewhat sometimes do, too often struggling to convince with their charisma credentials (see: Anyone But You). Action has gone from very bad to way worse with a lazy overreliance on the alienation of digital over the immersion of physical and even bigger budgeted films are still lacking that crackle and texture of real film. Industry fear has also increased the number of reboots, remakes and legacy sequels, all sleepwalking on fumes from years prior, zombies roaming the cinemas where humans used to be.

Which makes something like Speed, a tightly plotted, modestly budgeted and original action thriller led by two genuine movie star performances – one established, one emerging – and stuffed with action that feels urgent and involving, if not always plausible, feel like a bigger treat now than it even felt back then.

The story was hinged on a neat idea – a madman who attaches a bomb to a Los Angeles bus that will go off if it drops below 50mph – but it arrived in those post-Die Hard years, after a decade of Stallone and Schwarzenegger dominance, when the genre was starting to enter its parody era (quite literally the year before with Arnie’s Last Action Hero). Graham Yost’s original one-location script was first matched with the Die Hard director John McTiernan and centered around another wisecracking lead who ate rulebooks for breakfast. But the comparisons became a curse and instead, Speed started to transform into something different. It expanded outside of the bus with two big set pieces bookending and Reeves was cast as Jack, an atypical choice in many ways, better known for playing long-haired surfers or slackers (he marched straight to the gym to prepare for two months and shaved off almost all of his hair). Thirty-year-old Joss Whedon was also brought in, just a week before production started, to play with the script, excising glib one-liners and ultimately changing it to such an extent that even Yost admitted that he owned 98.9% of the dialogue in the finished movie.

What Whedon managed to do was give the film a fun zip without adding a smug smile. Reeves was allowed to play it straight, as determined and hyper-competent, and there were real stakes and consequences which meant that the action, as sense-defying as it often was, pulled us in that much closer. The cold open – set in a bomb-strapped office elevator filled with hostages – clued us in fast to how no-nonsense proceedings would be, little time for anything but the job at hand, a film that lived up to its title without feeling rushed or half-thought. De Bont choreographed the action with clarity, a modest-sounding skill that would mark him among the true greats within contemporary action cinema, and Yost/Whedon set up character with action reaction rather than clumsy exposition. We don’t need to know inner lives; we just need to know how well these people will operate under extremities. Jack is a focused problem-solver, whose heroics are led more by brain than brawn, a refreshing departure after a decade of the opposite. The opening set-up a simple yet involving dynamic with him and the bad guy, played by Dennis Hopper in delicious Batman villain mode, that has a tinge of the personal but is mostly professional, the goal being money.

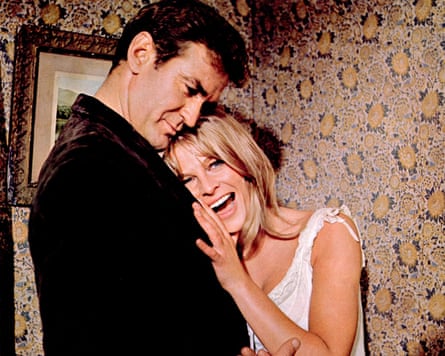

We head into the main set piece as if we’re in a disaster movie – a group of carefully curated archetypes (brash tourist, fragile older woman, impulsive young guy with a gun) trapped in one location – and, together with Mark Mancina’s all-timer action score, the tension is ratcheted up and then maintained until the bus is no more. We meet Sandra Bullock’s Annie, who becomes an accidental stunt driver, and there’s a restrained yet romantic buzz between her and Jack which, devoid of pause-and-breathe monologues about their past, works because of an easy chemistry that most romcoms would kill for (Meryl Streep allegedly being offered the role makes for a fascinating thought experiment). Bullock, who broke out the year before in Demolition Man, has that loose, nextdoor charm that puts us immediately, firmly on her side and it works brilliantly in life-or-death circumstances like these (as it did the following year in prescient cyber-thriller The Net or years later in Gravity). When they finally kiss, when some air is briefly allowed into the film after they’re off the bus, it makes sense in a way that it wouldn’t have before.

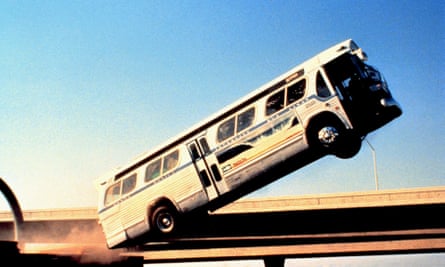

Much was made of the film’s big, batty stunt – the bus clearing a 50ft gap in the road – a credulity-obliterating jaw-dropper that has since been debunked on Mythbusters. But we didn’t really need it to be taken from film set to physics class. It’s not as if we saw it as hard fact at the time and it’s not as if we cared either, the film up until that point mostly existing within a heightened yet believable version of reality that didn’t allow for cheap writer cheats to propel the action. It was, and is, an exhilarating moment.

Fittingly for a film set in three different modes of transport, Speed is an engine that never runs out of gas, a lofty achievement at almost two hours. It’s as exciting now as it was then, although, as is often the case with many out-of-nowhere hits, Hollywood never quite figured out the lesson. There were other bomb-based thrillers in the years after – Sudden Death with Jean-Claude Van Damme, Chill Factor with Cuba Gooding Jr, Chain Reaction with Reeves himself – but none exploded in quite the same way. De Bont finally made an actual disaster movie with hit Twister but struggled elsewhere with anonymous studio hackwork like The Haunting and Tomb Raider 2. But his biggest mistake, along with studio Fox and Bullock too, was thinking that Speed itself could and should be franchised. While we like to think of this as a more modern problem, Hollywood has long attempted rubbishy and redundant follow-ups to films that didn’t need them (Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby, Revenge of the Stepford Wives, Staying Alive, The Sting II) and Speed 2: Cruise Control remains one of the all-time worst shoulda-quit-while-ahead sequels. Reeves wisely steered clear, although he did get a chance to showcase his connection with Bullock once again in 2006’s rather wonderful, and rather slept on, romance The Lake House.

The genuine embarrassment that Speed 2 left us all with has at least helped to prevent a more recent attempt to resurrect or relaunch the original. There’s no whisper of a too-cheap limited series or too-expensive legacy sequel bringing back Reeves and Bullock and having Barry Keoghan play the bitter bastard son of Hopper’s bomber, eager for revenge. We don’t need more Speed, but we do need more like Speed, more strategically budgeted and cannily crafted summer movies for adults, taken seriously but not overly so, delivered with a smile rather than a smirk and made with a full tank of gas.

Source: theguardian.com