Here is an intriguing, if not wholly successful, attempt to create a hero for gender-fluid times and give them the full mainstream period-film trimmings. In fact, the first half of this account of 19th-century bride Rosalie (Nadia Tereszkiewicz), who has a hormone disorder that covers her body in hair, almost resembles The Devil Wears Prada or another of those perky comedy-dramas about a young outsider who refuses to be cowed in their aspirations. In Rosalie’s case, by both the brutish mill workers of the community she marries into and by polite society.

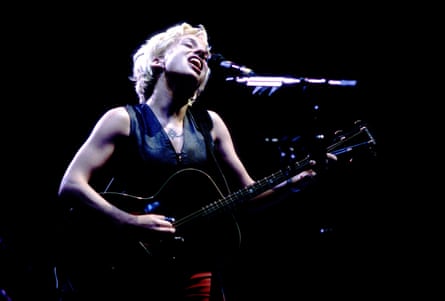

Director Stéphanie di Giusto has loosely based her film on the life of 20th-century “bearded lady” Clémentine Delait, transposing the story to 1870s Brittany. Rosalie is married off by her father, with a dowry, to cafe owner Abel (Benoît Magimel), who thinks he’s been sold a pup when his bride strips for the first time. Swallowing her humiliation, she bets her customers that, if she stops shaving, she can grow a more lustrous beard than similar fairground attractions. Already struggling with his feelings, Abel braces himself for the day of revelation, but stupefied and charmed locals pack out their cafe day after day. The couple, in debt to hooded-eyed estate owner Barcelin (Benjamin Biolay), may have found a quick financial fix.

With her furry strawberry-blonde ruff, Tereszkiewicz looks like a winsome Sir Francis Drake and her run as a burgeoning celebrity is fun, with a metropolitan journalist hoovering up her story. But it would have been nice to see Di Giusto run with this empowerment to make the film a more wanton, Orlando-like gender exploration. It opens up questions of appearance, femininity and conformity decently enough – but also ironically goes down the conventional route as it frames Rosalie as a tragic hero. In particular, the drama around Barcelin and his minions rounding on her to enforce the patriarchy feels manufactured.

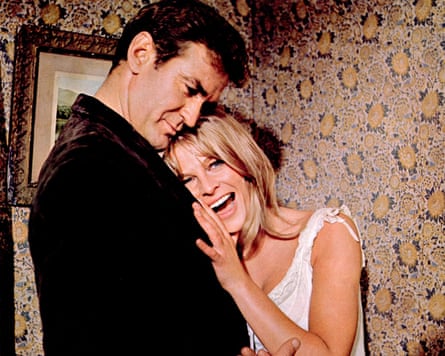

The negotiations between Abel and Rosalie ring more truthfully, with Magimel lumbering yet vulnerable in trying to juggle his need for respectability with his essential human decency. And Tereszkiewicz deploys a coy provocativeness as her character tries to enlarge her life and awaken her husband. In the end, the film takes on a predictable rhythm as society rallies against the couple, with pat aesthetic flourishes: fairytale allusions, abandoned flower bouquets. But the central private tussle is where the action is.

Source: theguardian.com