When Kathleen Hanna was 19 years old, a man broke into her apartment while she was out and attacked her roommate, Allee. The man beat her, dragged her by her hair and said he would rape and kill her but, as Allee fought back, he lost his grip, allowing her to run into the street and call for help. Hanna decided enough was enough. “You know when these big life events happen, like when someone close to you dies or gets cancer or is assaulted?” she says. “A lot of times they change us. I just thought: ‘This can’t happen again. How can I be part of the solution?’”

The answer lay just a few blocks from their apartment at SafePlace, a rape relief and domestic violence centre. Hanna, who was already a rape survivor, walked over and signed up for volunteer work. “It wasn’t me trying to be a good person,” she says. “I was in a moment of crisis and trying to figure stuff out, and it changed my life. If it wasn’t for the amazing people in Olympia, Washington, creating that space, I would never have had my eyes opened to what women live through. And then I may never have been in a feminist punk band. And then my life may never have happened.”

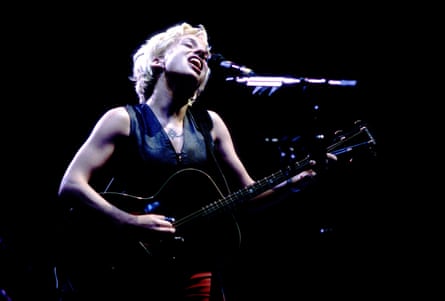

That band was Bikini Kill, the four-piece fronted by Hanna that lit up the Pacific north-west scene in the early 1990s and spearheaded riot grrrl, a youth movement protesting misogyny through music, meetings and zines. At gigs, Hanna famously called “girls to the front”, a practical measure to ensure the safety of female attenders that was also a neat encapsulation of their mission: to put women at the forefront of culture.

Mention of riot grrrl today provokes a comically exaggerated eyeroll from Hanna. “I’ve been asked the same questions for 25 years,” she explains in a tone that’s cheerful rather than combative. “I’ll be on my deathbed and someone will ask: ‘But what was riot grrrl, really?’ That’s why I wrote a book. I wanted to be one of those people who can be, like: ‘Turn to page 86 of my memoir. The answers are all there.’”

Titled Rebel Girl, after Bikini Kill’s biggest anthem, the book is the reason Hanna has interrupted her holiday to talk to me. She and her mother have rented a beachside villa in San Diego (Hanna lives two hours away in Pasadena); she moves her camera to show me gleaming floor-to-ceiling windows looking directly out to sea. At 55, Hanna’s look is the same as it ever was: high ponytail, heavy fringe swept to one side, pink lipstick, no-nonsense expression. Raw, candid and often bleakly funny, Rebel Girl details her troubled childhood; her college years and early adventures in music, both of which she funded by working as a stripper; her friendship with Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain (Hanna famously scrawled “Kurt smells like Teen Spirit” on Cobain’s wall, inadvertently providing the title for his band’s biggest hit); her post-Bikini Kill bands Le Tigre and the Julie Ruin; and her marriage to the Beastie Boys’ Adam Horovitz, with whom she adopted a son, Julius. The book also chronicles Hanna’s battle with Lyme disease, which would manifest in extreme fatigue, halting speech and occasional seizures, and wasn’t diagnosed until she was in her 40s.

But Rebel Girl’s most consistent theme is the awfulness of the men in her orbit. There’s her hard-drinking, sadistic father who struck fear into his family, once coming home drunk and threatening them with a gun. There are the men who raped her: the first, a boy from her school who found her passed out at a party; the second, a neighbour at her Olympia apartment block who, until that moment, Hanna regarded as her best friend. Then there are the scores of men affronted by her activism who threatened and threw missiles at her at gigs. Hanna would often wade into the audience to remove hecklers and gropers. “Male violence didn’t create me,” she writes, “it just made it harder to make my art – but I did it anyway.”

I tell Hanna I spent much of the book seething on her behalf. “Yeah, it was like whiplash,” she says. “Just when you’re recovering from one situation, another one happens. It felt important to include the small slights, the medium-sized ones and then the trauma with a capital T. I wanted to have a bit of all of that because that’s what a lot of our lives are like.”

On tour, Hanna made a point of talking about male violence during shows, leading young women to queue up after gigs so they could speak to her and share their own stories of abuse. Did that take a toll? “Oh for sure. It was really life-giving and healing at first but at a certain point I realised that had changed and I was using it to distract from dealing with my own pain. So that was also a big part of the book for me. I can’t keep dealing with other people’s issues for the rest of my life so I’m gonna write about my own.”

after newsletter promotion

Hanna says she cried a lot while writing. It got to a point where she had to stop for several months so she could go into therapy. “I was actually diagnosed with PTSD which was a great consequence of writing this book as it means I’m finally getting the treatment I need.” She used the journals she has kept since childhood to get into the mind of her past self. In one, she found a drawing from the late 1990s of a plane about to crash that was filled with people, many of them famous, who had crossed her. “I’m not at liberty to say who was on there but I will say there were about 22 of them,” she says with a grin. “[Drawing] is really helpful when people come after you for no reason, often publicly. It can be difficult to always take the high road, you know?” Male journalists, she says, would deliberately taunt her in interviews, accusing her of reverse sexism. “One thing I definitely found out being a feminist in a punk band in the public eye is there are a lot of men who really get off on watching a woman get angry.”

Along with the inevitable backlash against riot grrrl’s radical feminist ideology, there was also growing criticism that the scene was too white and too middle-class. Hanna held her hands up; in a series of lectures delivered on college campuses in her mid-40s, she directed students to the academic and zine author Mimi Thi Nguyen’s critique of the movement, Riot Grrrl, Race, and Revival. Hanna notes she never wanted to be “treated like this leader. I was 23, from a small town and clueless … Even the DIY thing, it wasn’t that I wanted to be in control of everything and do all this work. I just didn’t know there were managers or publicists. I didn’t know what a booking agent was. I had zero knowledge of any of that stuff.”

I wonder what Hanna made of the #MeToo movement, sparked by allegations against the now-jailed film mogul Harvey Weinstein, when women began sharing their stories of abuse on social media – essentially banging the same drum she’d been banging for 30 years. “There was this little bit of resentment,” she confesses. “Like, I wished I was 20 again so I could have had this experience of a larger public. But then I was, like, no, I’m really proud of these young people for taking this on and telling their stories and saying: ‘We don’t have to put up with this.’”

She is pragmatic, too, at the ways riot grrrl messaging has been co-opted over the years. It was Bikini Kill that came up with the term “girl power” for their second zine; later that decade, the Spice Girls adopted it as their slogan. In the Le Tigre song Deceptacon, Hanna sang: “Let me hear you depoliticise my rhyme.” “At the time, it felt bad that I couldn’t pay my rent and it seemed like the Spice Girls were making millions saying it,” she says now. “It felt like it was not the feminism that I cared about.” But she has since decided that “the phrase can be empty or it can be full. It depends what each person brings to it and I’m flattered and honoured that it is still a thing. And, you know, the suit guys? They know how to make money but they don’t know how to make art. I’m not gonna stop making stuff and they can rip it off all they want. I’ll just make something else.”

Making stuff and performing is that much sweeter since Hanna’s long period of incapacitation from Lyme disease. She has just got back from a tour of South America with the reunited Bikini Kill and is preparing for the European leg in June (she also intermittently performs with Le Tigre). “I’m in remission and I’m able to do everything now,” she says, with a look of satisfaction. “At shows I’m like a bull at a rodeo. I can’t wait to get out of the gate. There was this time when I was stuck in bed and I could barely go to the bathroom and I really thought: ‘This is the end.’ I don’t want to sound all born again, but to go from that to playing sold-out shows where everyone’s singing your lyrics? It’s pretty amazing.”

Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk by Kathleen Hanna is published by William Collins on 14 May.

Source: theguardian.com