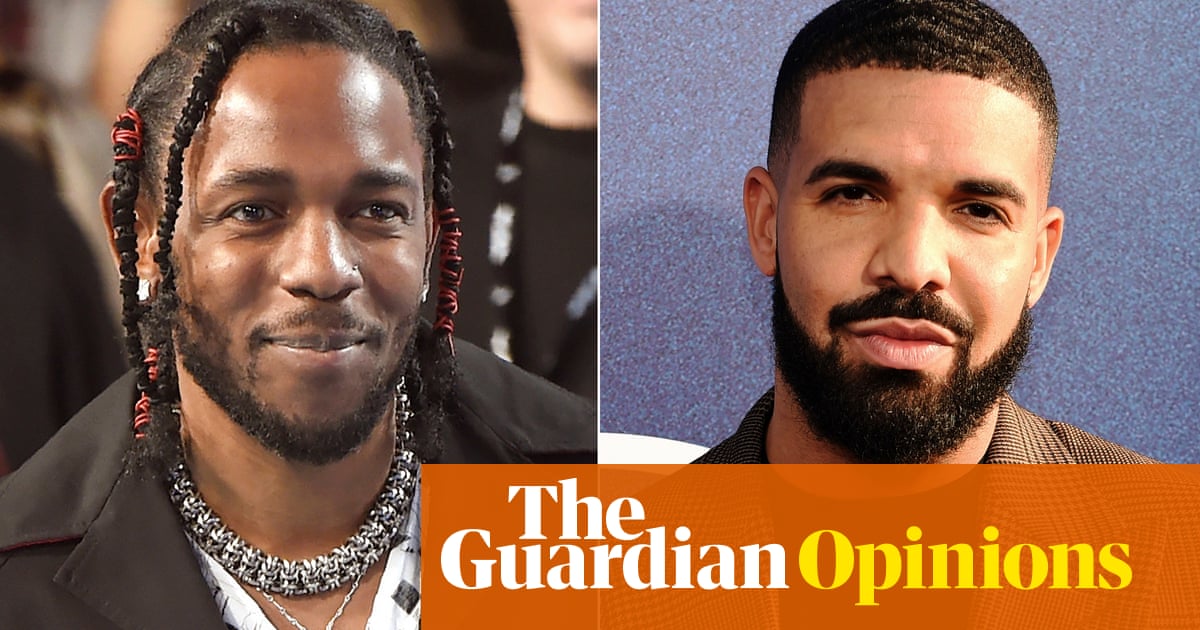

Drake and Kendrick Lamar have been battling it out for days in a vicious diss-track feud, but what started out as a sparring of wits between two of the world’s biggest rappers has quickly devolved into an excruciating game of who can expose the most damning thing about the other.

On his songs Meet the Grahams and Not Like Us, Lamar addresses Drake’s well-documented history of disturbing and inappropriate alleged behavior with minors, while on Family Matters, Drake has revived years-old domestic violence accusations against Lamar. Both Drake and Lamar deny any wrongdoing.

At one point, Drake even goes as far as to make fun of what he seems to have misunderstood to be a story about Lamar’s own experience of sexual abuse. (On 2022’s Mother I Sober, Lamar raps about child sexual abuse, which Drake assumes Lamar experienced himself.) What are we even doing here?

In the course of the nasty back-and-forth, they’ve made women – women who are possibly survivors of sexual abuse, harassment or domestic violence – the collateral damage of their violent mud-slinging.

Drake addressed the accusations against him with a line on The Heart Part 6: “If I was fucking young girls, I promise I’d have been arrested / I’m way too famous for this shit you just suggested,” he raps. The ironies of this denial would be darkly hysterical if they weren’t so sick. We all know the legal system is far from a reliable arbiter of justice and truth, but come on, Drake – really? That’s it?

These men are casually rapping about child sex abuse, domestic abuse and harboring secret children that they’ve presumably known about for years, but only chose to reveal when they were fighting.

And using each other’s possible victims as ammunition in a battle that has nothing to do with these women isn’t just perverse and morally reprehensible, it reveals the degree to which hip-hop and the music industry as a whole continue to protect terrible men even while their behavior or alleged behavior is an open secret.

When it comes to victimizing women, men rarely call each other out unless it’s convenient or beneficial to do so. Lamar had the nerve to admit as much. “We hate the bitches you fuck ’cause they confuse themself with real women / And notice, I said ‘we’, it’s not just me, I’m what the culture feelin’,” he raps on Euphoria.

The track records of these men show that they were fine being custodians of silence when speaking out did not serve their agendas. If Drake hates intimate partner violence so much, why has he loudly supported Tory Lanez, who is in jail for shooting fellow rapper Megan Thee Stallion? Lamar’s pretense of advocating for victims of sexual violence is also a grim joke: his last album featured Kodak Black, who was sentenced to probation in 2021 for attacking a teenage girl, who said he bit her on the neck and breast and persisted after she asked him to stop.

It’s tempting to dream of what things would be like if rappers decided to take a more radical approach to protecting women; if the “culture” that Lamar speaks of would actually hold its peers responsible, and if powerful men spoke up for their female peers as fiercely as they came together to protect one another.

Still, if there was one productive thing to emerge from this fight, it’s that it’s finally shining a serious light on the many problematic ways in which Drake engages with his Blackness and with cultures outside of his own.

At the end of the day, he is a biracial light-skinned Canadian who is able to (and happily does) manipulate his proximity to whiteness in ways that other darker- skinned, coarser-haired Black men who have actually lived the life that Drake fantasizes about on songs like Knife Talk never could. Of course, while Drake might be an interloper with gangster dreams who thinks going to jail scores you cool points, taking shots at his persona is a far cry from accusing someone of child sex abuse and the two denunciations not belong in the same world, let alone on the same diss track.

Ultimately, the best rap beefs strike a harmonious balance between entertaining and coldly humiliating. And it wouldn’t be a battle – surely not a good one – if they didn’t shoot below the belt. But this frenzied, brutal back-and-forth that’s supposed to point the finger at the ways the other person is a terrible human has only reaffirmed the code of silence that even enemies are willing to help each other uphold within hip-hop’s boys’ club.

Calling someone a pedophile or a groomer or a woman-beater simply doesn’t strike the right note when you knew about the allegations the whole time and only spoke up to win a fight.

-

Tayo Bero is a Guardian US columnist

Source: theguardian.com