Interviewed many years after the experience, Don Cherry said he would “never forget” the first time he heard the tenor saxophonist Albert Ayler. That was in Copenhagen in 1963.

I’ll never forget the time I first heard Zoh Amba, last March, at the Big Ears festival in Knoxville, Tennessee. A wealth of competing options at the festival makes it completely acceptable to drift in and out of performances mid-set, and many of the most exciting gigs featured young people we’d never heard of. Reliant on better-informed friends, my wife and I went where we were told. It was the guitarist Steve Gunn who suggested we see Zoh Amba, who, by the time we made it in, was 20 minutes into her set.

In a small, packed room, bathed in deep blue light, I recognised the drummer, Chris Corsano, but not the bass player. (Thomas Morgan, it turned out.) Amba was playing piano. Then she stood up: young, and very small, the tenor saxophone looked huge in her arms. But how it looked was nothing compared with how it sounded: a vast, joyous and pain-ridden honk and cry, an invocation and call. To whom? To Ayler, the ecstatic genius and self-described holy ghost of free jazz. This recognition was unmistakable and as instantaneous as Amba’s own response to his music when she discovered it as a precocious teenager searching the internet for something beyond straight-ahead jazz.

There are many things jazz performances must not be – but often are – and near the top of that list is a tribute act. Such a thing is redundant because so much of the history of jazz is, as Keith Jarrett’s album Tribute makes plain, precisely that: a form of creative tribute. Imitation, though, is worthless. The music that afternoon blazed with Aylerian power but it sounded new and fresh: sun-gold as potatoes pulled from the earth, trailing the soil of its roots in the Appalachian past. Amba, 23, grew up in Kingsport, Tennessee, 100 miles east of Knoxville and the residual homegrown influences in her sound – folk melodies, shards of gospel – perhaps serve a similar purpose for her marching bands and anthems did for the young Ayler in Cleveland, Ohio. This remained a lifelong passion. His Spirits Rejoice sounds as if it started out as a mangled rendition of La Marseillaise – or The Mayonnaise, as he called it. Watch footage of Tommie Smith’s and John Carlos’s Black power salute on the Olympic podium in Mexico in 1968 overdubbed with Ayler’s Ghosts turned up loud and you will witness the validity of Cherry’s suggestion that the tune should be adopted as the American national anthem.

That’s one aspect of Ayler’s legacy. The other is that his discordant and frenzied wailing remains the very sound of jazz’s refusal to go easy on the listener. He is, in this regard, its saving grace. In Cherry’s extraordinary reminiscence of playing with Ayler at that jam session in Copenhagen, he adds that he felt he was “in the presence of God”. As Amba’s set deepened – hymns sheering into chaos; bedlam aching and arcing towards serenity – I was in the grips of some mysterious communion. Mysterious because I am so content in my hostility to the idea of prayer – and yet that’s what this experience seemed like: a prayer, shared. All of this is understandable since the music makes audible a spiritual connection – spiritual unity, to borrow the title of Ayler’s iconic 1965 album – that Amba feels with her predecessor.

It needs emphasising that the tradition-threatening onslaught of free jazz has itself become a familiar part of that tradition. In Amba’s case this is easily trackable. After dropping out of the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, she took private lessons from David Murray. His first album, Flowers for Albert, was released in 1976, when he was slightly younger than Amba is now. Throughout the 80s and 90s Murray, who turns 70 next year, was nothing short of a saxophone colossus, both in terms of his relentless productivity and an ability to embody the entire history of the tenor. He was a living portal to Ayler, whose spirit was summoned to that blue room in Tennessee last March.

At some point Amba returned to the piano and played one-handed while continuing to blow the tenor. At the end of the gig – a drenched, profound and uplifting experience – everyone knew they had witnessed something extraordinary in the same way that, at a large auditorium on the other side of town, I knew after 20 minutes of Bill Frisell and Charles Lloyd that I was seeing motions being gone through.

Back home I listened to Amba’s album Bhakti but free jazz is not chamber music: what is overwhelming live becomes untenable on the stereo and sofa. I caught her live again in Brooklyn in October, thanks once again to Steve Gunn, who texted to say that he was playing with Amba alongside drummer Jim White (of Dirty Three) and Shahzad Ismaily on bass and keyboards. This was emphatically not Amba’s gig but the thoroughly democratic ensemble (now known as Beings) did nothing to dilute the scalding emotional intensity of her playing.

Where might music so extreme go next? In Ayler’s case, having failed to make good on whatever commercial hopes the Impulse! label had invested in him – thanks in part to the generous lobbying power of John Coltrane – he attempted to move into the mainstream with New Grass which failed to attract new fans and succeeded in attracting the derision of earlier admirers. Shattered by the breakdown of his brother Donald, whose trumpet playing had added an element of the bungled cavalry charge to musical proceedings, his behaviour grew increasingly strange. Three weeks after Ayler disappeared his body was found floating in the East River in November 1970. He was 34.

after newsletter promotion

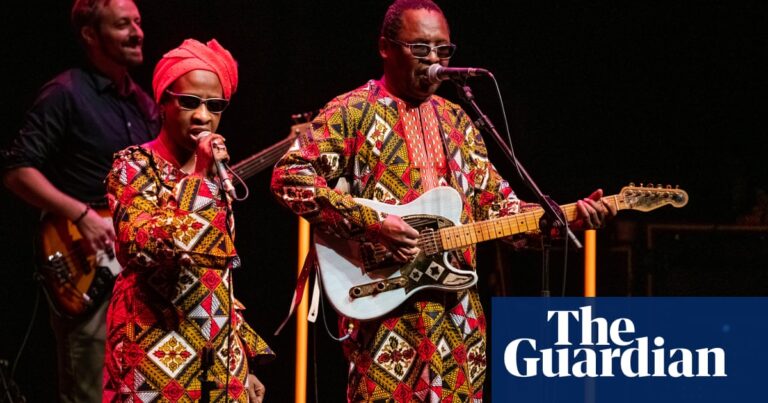

At the other extreme one can envisage seeing Amba half a century from now, playing a selection of ballads at Carnegie Hall or the Village Vanguard. But who knows where she will end up, what twists and turns her career might take? Tradition in jazz has to be a springboard into the future though one can rarely tell what this future will sound like. (Who could have predicted that Murray would rework the fierce majesty of Flowers for Albert so that it blossomed into a Cape Town-infused carnival and march?) That uncertainty or unknowability is consistent with the beating improvisatory heart of the music. For now the essential thing is that Amba is touring Europe, including a two-night stop at Cafe Oto in London. Wherever you catch her it will be a night to remember.

Source: theguardian.com