Grassroots venues are the foundation upon which the mighty British music industry has been built, fuelling the phenomenal level of talent this small island has produced. Yet while successive governments have shouted about how they are a shining demonstration of the country’s creativity, the very same people have cut funding and opened the cultural sector to the most brutal market logic. Alongside government neglect, small venues across the country also face rising trade costs, pressure on disposable incomes, greedy property developers, post-pandemic changes in attitudes to communal experiences and the continuing shift towards an increasingly screen-based lifestyle.

I cut my teeth DJing and dancing in small venues up and down the country, from my earliest experiences at Christie’s, in Sutton – when I’d head home after Carl Cox finished up as I had to be at school the next day – to a 10-year weekly Monday residency at Bar Rumba in Soho and many formative nights at the Hare & Hounds in Birmingham. There are countless more – far too many to list them all. If it weren’t for these backrooms, I would not be where I am today as a DJ. Nor would I have encountered (and still do!) those voices that push the culture forward and bring energy and positive momentum to our world.

The worry, of course, is that if these kinds of spaces disappear, we will end up with performances and DJ sets that all sound the same in places that all look the same, and where homogeneity becomes the status quo. The same sort of flattening of nuance is often levelled at algorithmically driven music discovery. And if this happens, we lose the joy of the unexpected find; the moment where you turn to the person next to you and laugh – what the jazz critic Whitney Balliett used to call “the sound of surprise”.

And that is why I think we should collectively work to preserve this special corner of our national makeup and fight against it fizzling out. The only way to do that is to open those spaces up and create access so that individuals can experience it for themselves. But to do that we also need to challenge some of the economic assumptions that govern these spaces.

The reality is that we live in a system where globally recognised names dominate the space and, albeit unwittingly, remove oxygen from those coming up. It is a bit like football. In the UK money has gone in at the top, resulting in the Premier League being the most lucrative in the world (with all the export value that brings); yet outside the elite clubs there is a real struggle to nurture and maintain grassroots clubs, as is often reported. Meanwhile in Germany there is a much more established practice of community ownership, with the 50+1 rule ensuring that the club’s members always own a majority stake. It may be that the Bundesliga is less “valuable” than the Premier League in monetary terms – but it makes it a more sustainable environment for the wider good of the game and places local communities at the heart of its financial stability.

So what can be done? To my mind there are two areas to focus on.

First, we need to find new economic systems for funding these smaller clubs so they can thrive, not just barely survive. In an excellent piece published a couple of weeks ago by John Harris on the “magic and messy glory” of Britain’s nightlife, he suggested a small levy on tickets in arenas and stadiums, which could flow back to independent venues. This makes sense to me. But perhaps we could also look at models of community ownership and cooperative practices that could shore up the foundational layer of smaller venues, much like those football models from abroad. If we were to follow the lead of the German clubbing model we could also keep ticket prices and fees affordable to encourage entry – perhaps there is something to learn from this.

Second, we need to borrow the principles of the “each one teach one” mantra of Tomorrow’s Warriors – the organisation that rose up out of the 80s jazz generation with a mission to educate and elevate young musicians coming through. Without its work, the most recent UK jazz generation – think Ezra Collective, Nubya Garcia, Shabaka Hutchings, Kokoroko and many more – might not have reached the heights they have, proving yet again the importance of education, funding and deep knowledge that only the grassroots can bring.

With all this in mind, this year I am going to redouble my efforts to play at small UK clubs as I have been doing – places like the Golden Lion in Todmorden, Cosmic Slop in Leeds, Sub Club in Glasgow. The aim is to keep shining a light on these special places and hopefully bring in audiences old and new in a way that gives back some of what they have given me and countless others. I am also going to gather those stories and use the media at my disposal to share them more widely.

I hope that through this journey to engage in a wider conversation about the importance of smaller venues. There will always be a section of the population drawn to the transcendental communal experience of dance and the “magic and mess” of seeing live music up close and in the flesh. But these life-affirming experiences – life-defining in my case – need the places and spaces to carry them. That is why I am determined to fight for their survival. I’ll hope you’ll join me.

-

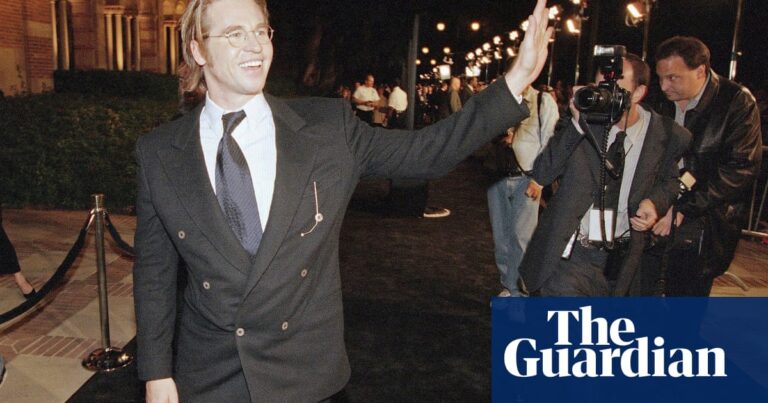

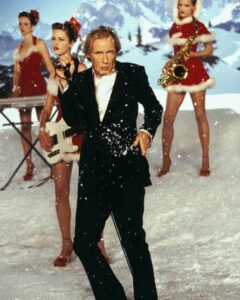

Gilles Peterson is a DJ, broadcaster and founder of Brownswood Recordings

Source: theguardian.com