T

Akashi Matsumoto and Haruomi Hosono were presented with a decision in 1969 when they began a rock band: should they sing the lyrics in English, the universal language of the genre at the time, or in their native Japanese? After discussing, the duo decided to use their native language, which ultimately revolutionized the music scene in their country.

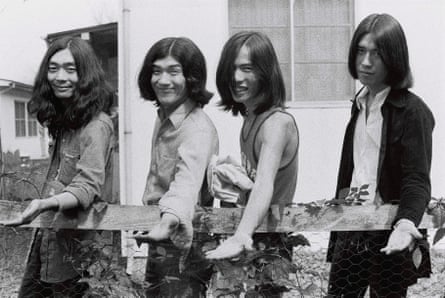

The band known as Happy End, comprised of guitarist Shigeru Suzuki and vocalist Eiichi Ohtaki in addition to Matsumoto, blended western folk-rock with Japanese lyrics, a decision that has had a lasting impact on various genres including the popular 80s funk style known as “city pop” and contemporary J-pop. According to 74-year-old Matsumoto, who spoke from a meeting room in Tokyo, Japanese is his native language and translating it alters the original meaning, thus changing his own instincts and words.

Happy End released three albums between 1970 and 1973, which have now been reissued on vinyl. However, the impact of the quartet has reverberated for decades. From the beginning, the band’s works were praised by domestic critics, with their 1971 album Kazemachi Roman being hailed as a masterpiece. It continues to rank highly on lists of the greatest Japanese albums. Co-founder Hosono explains, “At the time, musicians looked up to bands like Cream and Jimi Hendrix, and tried to imitate and outdo each other. But with Happy End, we decided to use our own words and create something truly unique.” Hosono went on to achieve even greater success with his later band, Yellow Magic Orchestra.

Happy End emerged from the band Apryl Fool, which Matsumoto and Hosono played in. While their psych-rock sound helped them stand out at a time dominated by groups replicating the sounds of the Beatles and the Monkees, Apyrl Fool’s lyrics were still sung in English – all except for a two-part song written in Japanese by Matsumoto: The Lost Mother Land, about the rapidly changing state of his hometown Tokyo, and everything lost alongside it.

View the image in full-screen mode.

According to Matsumoto, the 1964 Tokyo Olympics had a significant impact on the city. The construction of highways and freeways filled in the rivers and removed tram lines, which altered the landscape. However, this also resulted in obstructing the view of the sky.

After learning that Chu Kosaka had been cast in the Japanese production of the musical Hair, Apyrl Fool came to an end. During this time, Matsumoto recalls that both he and Hosono were becoming increasingly drawn to west coast rock bands like Buffalo Springfield, the Grateful Dead, and Moby Grape. They were inspired to create a new group that tapped into this musical scene. Hosono invited singer and guitarist Ohtaki to join the group, adding a melodic touch influenced by the Beatles and the Association. Matsumoto shares a humorous memory of Ohtaki’s realization about Buffalo Springfield’s music, which brought the group to a similar understanding.

Suzuki, the guitarist, completed the group. When asked about Happy End’s place in the Tokyo rock scene of the early 1970s, he said, “We shared our true and passionate thoughts without being constrained by adults. We were authentic – that’s the best way to describe us.”

Their first album received favorable reviews for blending hard-hitting and traditional Japanese sounds, sparking the “Japanese rock controversy” about the validity of rock music sung in languages other than English. In response, Happy End returned to the studio to reinforce the idea that Japanese rock could thrive independently. Lead singer Matsumoto explains, “We honed our skills and focused on our desired direction, fully embracing it.”

Happy End’s defining album, Kazemachi Roman, showcased their confidence. Matsumoto’s lyrics became more intricate, delving into the nostalgic pre-Olympics Tokyo he longed for. However, the strongest aspect was the band’s seamless collaboration and harmony. According to Matsumoto, this was exemplified in the album’s most well-known track, “Kaze Wo Atsumete”, which gained the band international recognition when it was featured in Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation. He likened the process of creating the song to playing catch, constantly refining the lyrics and melodies together.

disregard the promotion in the newsletter

after newsletter promotion

The song “Happy End” only achieved success in the commercial world much later on, but “Kazemachi Roman” received praise from critics and the creative community, leading to a decrease in the “Japanese rock controversy.” Matsumoto reflects, “I believe it’s fantastic… universally fantastic.” He admits that after their previous success, they wanted to experiment with different things and pursue solo projects, causing them to spend less time together. He jokingly adds, “I think Hosono just enjoys forming new bands. I was surprised once when I saw him writing down new band names on the Shinkansen (bullet train).”

The band Happy End would create their second album, also titled Happy End, at Sunset Sound Studios in Los Angeles. However, Matsumoto recalls that their thoughts were preoccupied with their individual career pursuits, which is evident in the songs on the album. He considers this to be a natural progression and not a negative development.

Suzuki went on to have a successful career as a solo artist. Ohtaki also had a beloved career as a pop artist and producer, releasing music until his passing in 2013. Matsumoto gained recognition as one of Japan’s top lyricists and collaborated with popular musicians. Hosono also had a diverse career. This year, a compilation featuring artists like Mac DeMarco covering Hosono’s work will celebrate the 50th anniversary of his solo debut. At 76 years old, he still actively creates and plans to start working on a new solo collection in the near future.

In the 21st century, the legacy of Happy End seems to have an even bigger impact. According to Matsumoto, previously all new music had to go through the US first and only then could it reach other places. However, with the availability of the internet and platforms like Spotify, people can easily discover fun and interesting music from various countries. Today’s music is global and no longer controlled by one particular location or dialect. While Happy End advocated for the strength of the Japanese language, their message can be applied to anyone expressing themselves in their own way. As Matsumoto states, everyone should use the language that allows them to express themselves comfortably, not just in Japan but anywhere in the world. There should be no limitations.

Source: theguardian.com