‘T

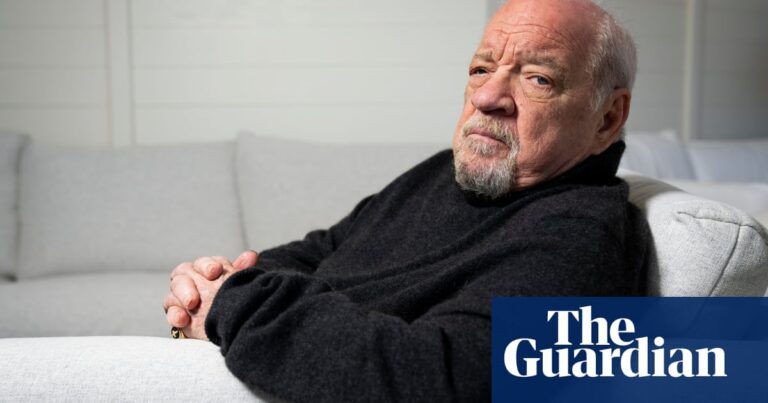

The effects of enslavement are not easily erased, regardless of efforts to mask them with bleach, new construction, or superficial displays of diversity. Poet and musician Camae Ayewa, also known as Moor Mother, speaks with a commanding presence, drawing your full attention even on a video call. It is evident within moments of speaking with her that her words hold weight and she speaks not to impress or entertain, but to share the truth. In a previous Guardian interview, Ayewa boldly stated that the repercussions of enslavement have yet to be adequately addressed, despite pushback and criticism from others. The question remains, have we truly faced the consequences of slavery?

This interview took place in 2017, and since then, the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests have brought conversations about systemic racism and colonialism to the forefront of public awareness. As a result, Ayewa’s reflections on our reluctance to confront the legacy of the slave trade are no longer considered radical. However, her doubts and concerns from seven years ago are still just as valid. She believes that not much has changed and that society has simply disguised the same issues in more modern forms. While technology and access to information have expanded, proper action and advocacy from governments and individuals have yet to be taken.

Ayewa’s latest album, The Great Bailout, is highly focused on criticizing Britain and its actions. Created in partnership with the London Contemporary Orchestra, the album delves into the horrors of British colonialism and the 1835 legislation that provided £20m (£17bn today) as compensation to 46,000 slave owners for their “property” that was lost due to the abolition of slavery.

In her song “All of the Money,” Ayewa reflects on the history of colonial violence, accompanied by the recurring question “where’d they get all the money?” Her vocals become more distorted as she delves deeper into this narrative, creating a captivating and emotionally intense experience. Despite popularity on a recent tour with the London Contemporary, Ayewa is uncertain how the song will be received when streamed globally. She acknowledges how listeners are drawn to certain pleasures and trends, and hopes this project will empower artists to create meaningful and significant music.

The song “Guilty”, featuring Lonnie Holley and Raia Was, establishes a hauntingly cinematic mood for the entire album with its layered vocals, whispers, string and horn accompaniments, and thought-provoking questions such as, “Did you pay for the trauma? The horror? The whip of the sugar cane?” Ayewa delves into the darkest parts of history with her interrogation – a topic she also explores in the Guardian’s “Cotton Capital” project, which investigates the connections between the newspaper’s founders and slave ownership. On her website, she urges listeners to consider the fact that none of the enslaved individuals received any form of compensation, while also pointing out that both William Ewart Gladstone (prime minister of Britain from 1868-1894) and David Cameron (prime minister from 2010-2016) are descendants of individuals who were given “compensation” after slavery was abolished.

What was the reason for this American artist to focus on British history? “I still have connections to the UK. As an African, our history is intertwined with the UK. I’m simply tracing our journey, the challenges we’ve faced, and how we’ve overcome them,” explains Ayewa. “My last name, Dennis, is of English origin. I had to question my identity and understand where I come from. Who is this person named Dennis?”

Ayewa was born in 1981 in Aberdeen, Maryland. She was raised in a public housing program and was politically aware from a young age. She explains, “As a child, I heard about various atrocities, such as the treatment of Indigenous communities in America and the history of slavery. These events radicalized me.” She recalls speaking up about Christopher Columbus in the third grade and expressing her dissatisfaction with his actions.

”

Ayema’s curiosity for knowledge is also reflected in their fascination with the Black experience and African communities that exist outside of the United States. Ayema was raised in an African Methodist Church and the word “African” held great significance for them, providing a sense of empowerment through its explicit connection. Growing up, Ayema developed a deep appreciation for diverse African cultures and had a strong desire to connect with people from different backgrounds. Whenever someone from Jamaica visited their area, it was a thrilling experience, akin to having a celebrity in the neighborhood.

Ayewa eventually relocated to Philadelphia to pursue a degree in photography at the city’s Art Institute. She also used writing poetry as a form of personal reflection, focusing on topics such as love and her frustrations. However, she was saddened by the passing of her favorite poets – Amiri Baraka, Maya Angelou, and Lucille Clifton. This inspired her to continue the tradition and honor their legacy. Ayewa views poetry as a powerful tool for healing, but acknowledges that not everyone can be a poet. She compares it to being a doctor, where one must have a certain level of skill and knowledge before performing surgery. Similarly, being a poet is a unique and intricate craft that requires a different type of skill and thought process.

Display the image in a full screen mode.

She teamed up with her closest companion, Rebecca Roe, to create the Mighty Paradocs, a rap duo. She then joined forces with saxophonist Keir Neuringer and bassist Luke Stewart to establish Irreversible Entanglements, a free jazz group that integrates music with activism. Their music is captivating, innovative, and revolutionary, drawing inspiration from Ayewa’s favorite artists such as Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, John Coltrane, and Saul Williams.

The first solo album released by Moor Mother, titled Fetish Bones, was in 2016. This album combines elements of spoken word, hip-hop, and field recordings to tell stories of survival and resistance. Since then, Moor Mother has performed in both small DIY venues and prestigious stages like London’s Barbican. Some have called her “the poet laureate of the apocalypse,” but she doesn’t find this label to hold much value. She explains that while she understands the need for categorization, she has never even mentioned the word “apocalypse” in her poetry or music. She also mentions her involvement in the collective Black Quantum Futurism, where they reject the idea of endings and instead see everything as part of a continuous journey.

Ayema’s unique sound and storytelling in The Great Bailout serves as evidence of her revolutionary ideas and political beliefs. She firmly believes in sharing the truth about what is often overlooked or overlooked. As she states, it is important for someone to bring these truths to light.

Source: theguardian.com