I

In just three weeks, the credits will roll on what has been considered the greatest season for cinema in recent years. Ten films have been nominated for the best picture Oscar on March 10 and not one of them is considered a disappointment. This is uncommon, as there is usually at least one lackluster film in the mix (such as Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close). Sometimes there may even be multiple subpar films (like Babel and The Blind Side) or even a trio (Crash, Les Miserables, Bohemian Rhapsody). It’s not always easy to get excited about the awards race, and it can be difficult to have strong opinions about the top contenders.

This year has been unique. The quality has improved and the audience has been highly engaged. A lot of this can be attributed to the Barbenheimer juggernaut, which has given smart and popular movies their moment post-Covid. However, even without this, there would have been lively discussions surrounding The Zone of Interest, Anatomy of a Fall, and Poor Things, all of which are bold and unique works of art that have sparked passionate debates.

What other items are included? A delightful and flexible first work of American fiction. The Retained: flawless winter illumination. Previous Experiences: a modern version of Brief Encounter for those who use Skype. Maestro: a passion project with emotional depth and impressive fake cheeks. Additionally, an enormous masterpiece by Scorsese.

These are only the movies that the Academy has preferred. They have excluded Passages, Monica, Showing Up, and possibly the best movie among the titles in the lineup: All of Us Strangers.

2023 could potentially be the greatest year for film since 2013. Movies like The Act of Killing, 12 Years a Slave, Gravity, The Great Beauty, Frances Ha, A Touch of Sin, Nebraska, The Wolf of Wall Street, and Under the Skin have all contributed to its strong claim. However, it remains to be seen if it will surpass all previous years in cinema history. In this article, our writers passionately defend their top choices for the best years in film. Catherine Shoard

In 1971, there was a surge of exceptional films released.

The significance of 1971’s movies is made complex by the themes of nihilism, pessimism, violence, overwhelming despair, and disillusionment that were prevalent in many of the noteworthy films released that year. These were not uplifting films that could be easily condensed into a montage set to the tune of “That’s Entertainment.” Instead, they often depicted characters who were struggling with madness, paranoia, disillusionment, and exhaustion with life. Even the well-received Fiddler on the Roof directed by Norman Jewison tackles the topic of pogroms.

When Gustav von Aschenbach, played by Dirk Bogarde, is carried away from the beach in Death in Venice with hair dye running down his face, it’s a powerful symbol of defeat. The themes of morbid passion, artistry, and decadence depicted in the film were very representative of the year 1971. This was also reflected in Ken Russell’s controversial film The Devils, which pushed boundaries and challenged societal norms. Dušan Makavejev’s WR The Mysteries of the Organism, although released in the 60s, had a similar eroticism but lacked the dark undertones seen in 1971. Peter Bogdanovich’s exceptional film The Last Picture Show was wrongly seen as foreshadowing the death of cinema, but the iconic naked-swim scene remains as vibrant and impactful as ever.

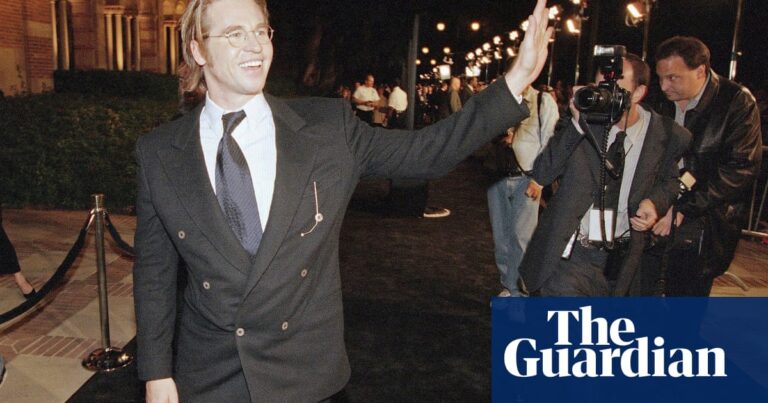

Display the image in full screen mode.

A Clockwork Orange by Stanley Kubrick depicted a frightening world where the government had complete control and a hatred towards the younger generation. Straw Dogs by Sam Peckinpah was a terrifying portrayal of violence in rural Britain, while The French Connection by William Friedkin was a gripping thriller about New York descending into chaos. Dirty Harry, directed by Don Siegel, introduced us to a tyrannical law enforcement officer who takes on all the unsavory tasks. Richard Fleischer’s 10 Rillington Place featured Richard Attenborough as a sleazy and depressed serial killer in a similarly sleazy and depressed Britain. Lastly, Mike Hodges’ outstanding film Get Carter provided a satirical commentary on the British social class system, sense of shame, and vindictive nature.

What led to the sudden surge of outstanding films in 1971? In Britain, it coincided with John Trevelyan’s retirement as the liberal head of the British Board of Film Censors. He had played a role in fostering an environment for bold and boundary-breaking films. Additionally, the shift from 1960s counterculture to a more rebellious and confrontational atmosphere contributed to this trend. Most importantly, film-makers were advocating for the freedom to express themselves, which in itself was a form of rebellion. This made 1971 a particularly exhilarating year for cinema. -Peter Bradshaw

In 1928, three films directed by Alfred Hitchcock were released.

Creativity and contradiction are born out of chaos. In the early days of sound cinema, Hollywood was thrown into disarray as studios rushed to adopt new synch-sound technology in 1928. However, this year also saw the emergence of some of the greatest and most emotionally powerful silent films in American cinema. The Wind, directed by Victor Sjöström, tells the story of Lillian Gish standing up against male violence amidst a storm. King Vidor’s The Crowd portrays the failure of American dreams, while Josef von Sternberg’s The Last Command exposes the inner workings of Hollywood. Charlie Chaplin’s final silent film, The Circus, is both heartbreakingly poignant and uproariously funny. Even a light and charming film like Paul Fejos’s Lonesome managed to incorporate some dialogue. Meanwhile, on the Mississippi River, the era of American comedy came to an end as Buster Keaton starred in a silent steamboat and Mickey Mouse took the helm in a talking one, marking the beginning of a new era.

In other places, Soviet film created notable works like Storm over Asia by Vsevolod Pudovkin and October by Sergei Eisenstein, while Alexsandr Dovshenko brought about the bizarre imagery of Zvenigora. Fritz Lang captivated German viewers with his intense spy movie Spione, René Clair perfected the art of French silent comedy with The Italian Straw Hat and Les Deux Timides, and in Britain Alfred Hitchcock released three films within a year. Across Europe, the revolution of cinema was underway as filmmakers dismantled and reassembled its rules, influenced by surrealist artists like Germaine Dulac (The Seashell and the Clergyman) and Man Ray (The Star Fish) – while Luis Buñuel and Jean Epstein created the strangely dreamlike Gothic horror The Fall of the House of Usher.

Surpassing all of these, a filmmaker from Denmark and an actor from Italy joined forces in France to create the exquisitely crafted film, The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). Through intimate close-ups of Falconetti’s tearful face, director Carl Theodor Dreyer delved into the depths of human emotion. The use of unconventional techniques perfectly complemented the timeless story, showcasing the boundless potential of cinema as an art form. As noted in a recent essay by Virginia Woolf, this film remains unmatched in its ability to showcase the full capabilities of cinema.

1991: The present is influenced by the past.

The T-1000, a lethal liquid metal robot, emerged from the checkered floor like a terrifying nightmare in Terminator 2: Judgment Day. It outmatched the original Terminator and even Arnold Schwarzenegger’s seemingly indestructible character. The first Terminator film was a surprise success, but the sequel took it to the next level with a villain who could transform into any object it came into contact with.

Selecting the year 1991 may seem unexpected, especially considering the more prominent 90s years in the film industry. These included the successful releases in 1994 such as Pulp Fiction, Forrest Gump, and Shawshank Redemption, as well as 1997’s Titanic, directed by James Cameron. However, the films from 1991 have a way of resonating with the present. For example, Terminator 2 marked the beginning of CGI technology, which led David Foster Wallace to come up with the “inverse cost and quality law” in an essay that went against popular opinion (as he disliked the film). This law suggests that the higher a movie’s budget is, the lower its quality will be. This debate carries on even decades later with the rise of superhero movies.

The themes continue. In the midst of recent global discussions on discrimination based on race and gender, there has been much delight in rediscovering Daughters of the Dust, a touching tale by Julie Dash that follows three generations of Gullah women living on the sea islands of South Carolina. John Singleton’s Boyz N the Hood portrayed young Black men navigating police intimidation and gentrification. Ridley Scott’s Thelma and Louise celebrated female friendship and liberation from male violence. The big winner at the 1991 Oscars, Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs, is the only horror film to ever win Best Picture, sparking a conversation about “prestige horror” in recent years. And on the topic of lengthy films, I had the opportunity last year to see Edward Yang’s four-hour masterpiece A Brighter Summer Day at the theater. The story of student life in 1960s Taiwan is beautifully told and never feels drawn out over the lengthy runtime; by the end, I was moved to tears. Rebecca Liu

In 1999, the film industry was plagued with fear due to Y2K anxiety.

The 1990s may have revealed a worrisome increase in reliance on franchises, but it also ended with a reminder of the potential for achievement outside of established boundaries. 1999 marked the conclusion of a decade that saw the emergence of a new independent film movement. The films associated with this movement exude an energy and willingness to take risks that has not been matched in subsequent years.

We witnessed unique first works from Sofia Coppola, whose heart-wrenching film The Virgin Suicides remains unparalleled, her former partner Spike Jonze with Being John Malkovich, and Lynne Ramsay with the chilling coming-of-age story Ratcatcher. The emerging group of filmmakers who had made their mark in the 90s continued to thrive with Paul Thomas Anderson’s daring Magnolia, David Fincher’s explosive Fight Club, Mike Judge’s soon-to-be-appreciated Office Space, Tom Tykwer’s Run Lola Run, Doug Liman’s Go, and Alexander Payne’s brutally comedic Election.

Even the more star-driven studio movies were better and smarter than usual: Anthony Minghella’s The Talented Mr Ripley, David O Russell’s Three Kings, Frank Oz’s Bowfinger and John McTiernan’s The Thomas Crown Affair. Horror was also on the upswing with The Sixth Sense, Audition and the subgenre-creating The Blair Witch Project while fears over our increasingly connected world also led to David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ and The Matrix, the rare franchise-starter that felt genuinely original (remember those?).

Many others share this belief. In 2019, a book was released that argued the same point, while a panel in London also discussed this topic. Recently, Alamo Drafthouse theaters in the US have been screening some of the top films from that year, with most showings being sold out. It’s possible that there was a fear of Y2K causing anxiety in the industry before everyone decided to play it safe instead. This idea was also discussed by Benjamin Lee.

In 1968, there was a monumental advancement in the world of cinema.

In 1968, the counter-culture movement began to greatly influence the film industry. One particularly noteworthy event was the release of 2001: A Space Odyssey, which revolutionized filmmaking techniques and design. The film’s connection to psychedelia was a coincidental marketing strategy for MGM, who promoted it as “the ultimate trip”.

In the same year, another person from New York (Kubrick, who moved to Britain) left a lasting impact on popular culture. This person was Barbra Streisand in the daring, clever, and unapologetically Jewish musical-comedy Funny Girl. While movies featuring silly female characters were not uncommon, very few could sing as well as Streisand and still maintain enough allure to attract Omar Sharif.

Display the image in full-screen mode.

In 1968, the Polish filmmaker Roman Polanski released his first American movie, a satirical take on New York City’s real estate industry called “Rosemary’s Baby.” It remains one of the most notable films about paranoia and manipulation, alongside the classic “Gaslight.” That same year, director John Cassavetes also made a major impact with his documentary-style film “Faces,” shot on a low budget and focused on complex character dynamics. In Hollywood, Steve McQueen’s “Bullitt” shook up the action genre with its intense car chase set in the hills of San Francisco, leaving audiences breathless. And in outer space, Charlton Heston starred in a socially conscious action film called “Planet of the Apes,” where he landed on a planet that bore a striking resemblance to Earth.

In 1955, a cry of youthful frustration energizes a whole generation.

The era of the mid-50s is frequently disregarded as a difficult period of change between Hollywood’s Golden Age and Italian neorealism on one side, and the rise of New Wave movements and counterculture cinema on the other. However, in response to the growing competition from television, the film industry introduced the captivating and visually stunning features of VistaVision, Technicolor, and CinemaScope. This enhancement even made black-and-white films stand out.

The year 1955 saw a shift in the film noir genre, as it took on a dreamy southern gothic feel in Charles Laughton’s acclaimed film The Night of the Hunter. Starring Robert Mitchum as a charismatic con man, the film captivated audiences with its biblical themes and rural setting. Around the same time, Robert Aldrich’s gritty film Kiss Me Deadly marked a move towards Cold War themes, highlighted by a mysterious briefcase that hinted at impending doom. Meanwhile, in France, the bar was being raised in other genres as well, with the psychological thriller Diabolique and the groundbreaking diamond heist in Rififi.

Display the image in full screen mode.

The colors in 1955 may have appeared extremely vivid, but they were matched by intense emotions. For example, Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows portrays a romantic relationship between a widow and her gardener, which blossoms in a stifling environment of gossip and societal expectations. There are also the alluring delights of Max Ophüls’ Lola Montes, which centers on the tragic life of a 19th-century European dancer and courtesan within a literal three-ring circus. Even the year’s entertainment options were swoon-worthy, ranging from Jean Renoir’s French Cancan set in the Moulin Rouge to Frank Tashlin’s popular Martin-and-Lewis film Artists and Models, to Katharine Hepburn’s iconic Venice canal scene in David Lean’s Summertime.

All these trends coalesced in the beautiful, tragic year of James Dean, which started in the spring with Elia Kazan’s East of Eden and ended posthumously in the fall with Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause. Two CinemaScope pictures – one in black-and-white, the other in colour, both howling with a young angst that would galvanise a generation. Scott Tobias

In 1982, there were signs of reactionary forces and subversive actions in the atmosphere.

However, there was also an atmosphere of rebellion: 1982 was a significant year for science fiction, horror, and fantasy, genres that were still scorned by many mainstream critics but well-received by younger viewers. While ET: The Extra-Terrestrial dominated the box office, negative reviews or low profits caused other iconic films like The Thing, Blade Runner, and Cat People to take more time to gain a dedicated fan base.

Tron and Koyaanisqatsi broke new ground, Poltergeist and Creepshow nudged horror into the mainstream, and Conan the Barbarian and The Beastmaster boosted heroic fantasy. First-rate sequels Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and The Empire Strikes Back heralded the ascent of blockbuster franchises. At the opposite end of the budgetary scale, Q: The Winged Serpent, Tenebrae, Liquid Sky, Android, Basket Case and other gems all benefited from the rep circuit and the proliferation of VHS.

Other noteworthy releases in 1982 included First Blood, Moonlighting, 48 Hrs, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, The Draughtsman’s Contract, The Year of Living Dangerously and Tootsie. Additionally, Diner and Fast Times at Ridgemont High introduced a fresh wave of talented actors.

The three major figures of New German Cinema each debuted new movies: Fitzcarraldo by Werner Herzog, The State of Things by Wim Wenders, and Veronika Voss and Querelle by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who passed away from a drug overdose in June 1982. Samuel Fuller showcased his talent with the controversial White Dog, Ingmar Bergman released his acclaimed final film Fanny and Alexander, and British critics harshly criticized Lindsay Anderson’s satirical masterpiece Britannia Hospital. This was to be expected as the film attacked the values of the establishment. Anne Billson.

In the year 1960, there were visually pleasing warning shots being fired.

According to author Mark Harris in his book Scenes from a Revolution, the year 1967 marked a significant shift from Old Hollywood to New Hollywood. However, there were already rebellious movements happening in various countries at the beginning of the 1960s. In fact, 1960 could be considered one of the most influential years in film, with numerous bold artistic statements being made. One of the most notable examples was Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, which defied the traditional standards of the Hays Code and shattered film conventions in its iconic shower scene.

The year in Hollywood was not considered a classic, as only The Apartment by Billy Wilder, The Magnificent Seven by John Sturges, and Spartacus by Stanley Kubrick stood out. This emphasized the diverse and groundbreaking offerings from other countries. Jean-Luc Godard, a pioneer in film language, released Breathless, the flagship film of the French New Wave, while François Truffaut and Louis Malle continued the movement with Shoot the Piano Player and Zazie dans le Métro. In the UK, Karel Reisz introduced the more contemporary British New Wave with Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, while Michael Powell shocked audiences with his serial-killer film Peeping Tom, questioning the very purpose of cinema.

In 1960, a wave of revolutionary films such as Village of the Damned, Eyes without a Face, L’Avventura, Purple Noon, and The Housemaid reflected a sense of unease and displacement that signaled impending change. While Ozu’s Late Autumn and Visconti’s Rocco and his Brothers were more traditional works, they were still part of the exciting global cinema movement that emerged as Hollywood declined and paved the way for the new generation of filmmakers. If we consider both impact and quality, 1960 was a pivotal year that opened up numerous possibilities.

1939 marked the peak of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

The Oscar collection was dominated by Gone with the Wind, Mr Smith Goes to Washington and The Wizard of Oz. In addition to his successful minor project Drums Along the Mohawk, John Ford produced two undeniable masterpieces Stagecoach and Young Mr Lincoln, which can be likened to discovering the cure for polio and breaking the world record for the fastest mile in the same year. Whether in drama, comedy, or action, romance had never experienced such a productive year, with impressive films such as Ninotchka, The Women, Goodbye Mr Chips, Wuthering Heights, and Only Angels Have Wings. Basil Rathbone made his first appearance as Sherlock Holmes in The Hound of the Baskervilles. Even the lesser-known B-movies, popular films like the third installment Son of Frankenstein, showcased a level of skill and dedication in performance that is foreign to today’s franchise-driven industry.

:

However, if we consider the true significance of the art form, 1939 can still be considered a standout year. It was a pre-planned milestone, commemorating 50 years of motion picture technology and 25 years since the industry moved to the west coast. Each studio showcased their talent both on and off the screen, with larger budgets and grander ambitions, elevating the already impressive artificiality that the dream factory sold to a captivated American audience. At the same time, 1939 also reflected the currents of history in a less orchestrated and sometimes unflattering manner. For example, Anatole Litvak’s Confessions of a Nazi Spy exposed the flaws of the United States’ isolationist policy prior to World War II, while Gunga Din, set in India, perpetuated ethnocentric fantasies of the “Thuggee murder cult” amidst its adventure-filled storyline. Glitzy and ostentatious, politically progressive yet narrow-minded, masterful yet commercially driven – this was Hollywood at its most glamorous during the peak of the Golden Age. Charles Bramesco:

2013: the winds of change

The film industry has undergone significant changes in the past decade, with the impact of Covid, streaming, MeToo, and Black Lives Matter. However, these changes were foreshadowed as early as 2013. One notable example was Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave, a powerful drama based on Solomon Northup’s memoir, which not only won the best picture Oscar but also marked a turning point for Black American filmmakers. This was also a time when female directors were finally gaining recognition, with notable names such as Sofia Coppola (Bling Ring), Clio Barnard (Selfish Giant), and Joanna Hogg (Exhibition), as well as actress Greta Gerwig in Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha.

Despite the emergence of new talent, established American filmmakers continued to produce impressive work. Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street was a surprise hit, the Coen brothers delivered the brilliant Inside Llewyn Davis, and Jim Jarmusch created the humorous vampire-rock film Only Lovers Left Alive. At the same time, international filmmakers made significant strides, with Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty receiving widespread acclaim, Pawel Pawlikowski’s faith drama Ida winning the best foreign language film Oscar, and Lars von Trier shocking audiences with his four-hour erotic dreamscape Nymphomaniac.

This list is impressive, and it doesn’t even mention two of my personal favorites. These two films showed a new direction for the industry. Gravity used advanced visual effects and a realistic portrayal of space to push the limits of what was possible in a film. Meanwhile, Under the Skin, directed by Jonathan Glazer of Zone of Interest, defied expectations and redefined what was considered acceptable for a major film featuring a big star. 2013 was truly a year to remember.

In 1975, the absolute best was declared and the case was concluded.

It is difficult to overlook 1975 as the year that best forecasted the future of Hollywood in terms of excellence, originality, and stunning impact. It was a year where the rising New Hollywood cinema intersected with the emerging blockbuster genre. The outcome of this collision was inevitable – a massive great white shark weighing three tonnes and craving sunbathers would emerge victorious.

Jaws is often considered the catalyst for the current trend of unoriginal blockbuster films, but it remains a remarkable example of mass entertainment with its impressive use of technology and storytelling, solidifying its place among the nominees for the 1975 Academy Award for Best Picture. In fact, the 1975 shortlist may be one of the strongest in history, with no weak entries like the dated Towering Inferno from the previous year. Along with Jaws, the list includes Kubrick’s epic Barry Lyndon, Altman’s sprawling country music masterpiece Nashville, the powerful Dog Day Afternoon featuring stellar performances from Pacino and Cazale, and the ultimate winner, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Display the image in full screen mode.

The year was packed with noteworthy movies, including five standouts. However, there were also many other significant releases. It was a time for ambitious and boundary-pushing films, such as Ken Russell and The Who’s daring rock opera Tommy, Warren Beatty’s satirical political comedy Shampoo, Pasolini’s shocking arthouse film Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, and the exhilarating experience of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The movie’s bold rejection of societal norms regarding sexuality and gender made it a groundbreaking moment in queer cinema. But it was not the only film making an impact in 1975; Dog Day Afternoon featured a compassionate portrayal of a transgender character – Cazale’s Leon, seeking gender-reassignment surgery – long before other notable films like The Crying Game, Boys Don’t Cry, or Tangerine. Black cinema also had significant releases in 1975, such as the coming-of-age drama Cooley High, which helped shift representations of black communities from the exploitative Blaxploitation genre to more authentic and well-rounded depictions, and Horace Ové’s pioneering film about Black British life, Pressure.

Not yet convinced of the worth of 1975? I could mention the intense thriller Three Days of the Condor starring Robert Redford, Fellini’s autobiographical masterpiece Amarcord, or Gene Hackman’s impressive performance in the lesser-known paranoid thriller Night Moves, similar to his role in The Conversation. But perhaps it’s best to simply state that according to Sight and Sound’s critics poll, the top film of all time was released in 1975: Chantal Akerman’s groundbreaking slow cinema film, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. The decision is clear. Gwilym Mumford

In 1946, the studio system was thriving.

The figures speak for themselves: the year with the highest movie attendance of all time was 1946, with over 90 million weekly admissions – which accounted for 60% of North America’s population.

During this time, the studio system was thriving and renowned directors John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, and Howard Hawks were at the peak of their abilities. The popular film genre of film noir was also at its pinnacle, with Hawks’ The Big Sleep setting the standard. Meanwhile, Ford crafted one of his most emotionally-charged westerns, My Darling Clementine. Actresses Joan Crawford and Rita Hayworth delivered some of their best performances in Mildred Pierce and Gilda respectively, while Cary Grant’s portrayal in Hitchcock’s Notorious was highly praised.

During this time period, Italian neorealism was highly popular in Europe, highlighted by Vittorio De Sica’s Shoeshine and Roberto Rossellini’s Paisà, both filmed in the aftermath of Europe’s bombings. In France, Jean Cocteau created one of his best works, La Belle et la Bête. This era marked a unique closeness between America and Europe, where Hollywood was not solely focused on creating fantasies.

After their triumph over fascism, Hollywood was exhausted from the sacrifices they made. They resembled a restless dreamer, plagued by intense and chaotic dreams. William Wyler directed the unsettling and thought-provoking Oscar-winning film, The Best Years of Our Lives, which explored the struggles of returning veterans. The beloved classic, It’s a Wonderful Life, directed by Frank Capra, also takes on a darker tone than we may remember. This is fitting for a film created by two veterans who were forced to confront the harsh reality of slumlord capitalism before giving George Bailey his happy ending.

The period of success eventually came to an end. In 1947, fewer people attended movies as more couples chose to stay at home and watch TV instead. This led to a significant decline in movie attendance that has never fully rebounded. – Tom Shone

In 2027, the best is yet to come.

I never imagined I would live to see such a chaotic year. It all started with the end of the Academy’s hundredth anniversary celebration. Finally, the declining number of viewers and the overwhelming number of sub-categories and voting groups have reached their inevitable fate. “Enough is enough!” exclaims Spike Lee, the last president, as he receives his directing award for No One Asked Me.

Quentin Tarantino delivers his third final film, GloriUS. The SURveillance channel buys out Netflix and breaks viewing records with Chez the Kelces, a two-week coverage of you know who.

Daniel Day-Lewis is back on the big screen, starring in Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film, Last Dream of a Dressmaker. However, 81% of moviegoers are left wondering, “Who is Daniel Day-Lewis?”

According to reports, the TRUMP media park is facing issues with its special effects. Trump has declared, “It’s a confirmed decision – Brad Pitt will portray me.” However, Pitt has since left the country. Trump commented, “Who would have thought? He ended up being so unpleasant.”

Stephen Frears received the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival for his introspective piece, What I Chose Not to Create. Jane Campion debuted Tender Will Be the Night, starring Benedict Cumberbatch as Dick Diver and Margot Robbie as Nicole.

Martin Scorsese unveils a four-hour version of Big Horn, a film depicting the 1876 battle as a representation of America’s moral corruption. Leonardo DiCaprio portrays Custer, with Robert De Niro playing Sitting Bull.

Elon Musk has purchased the former Academy Museum in Los Angeles. The United States currently has 211 functioning movie theaters. Despite ongoing legal disputes between Princes Harry and William, Peter Morgan has committed to continuing production of The Crown.

Seven lost cans of the film The Magnificent Ambersons are discovered on the beaches of Puerto Vallarta. At the age of 97, Frederick Wiseman creates a four-hour movie titled Quiet, depicting the world as a quiet and still landscape. The sound design is done by Walter Murch. Wiseman declares, “That’s a wrap!” – David Thomson.

Source: theguardian.com