I

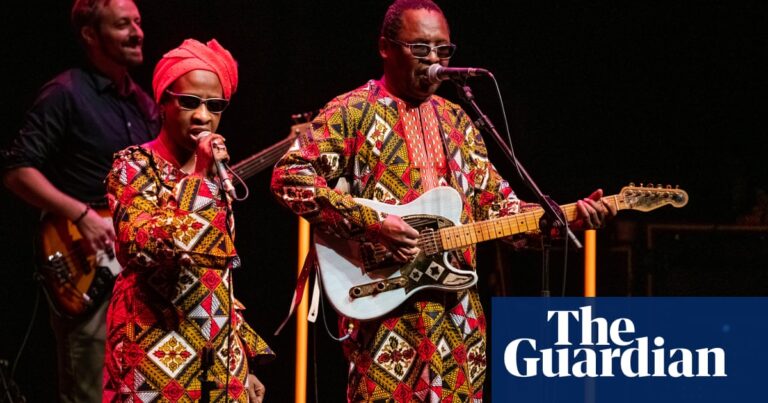

At the National Philharmonic Hall in Warsaw, Joshua Bell, a violinist, and Dalia Stasevska, a conductor, are working diligently to perfect the initial notes of a concerto. The piece commences with a set of prominent chords from the woodwind section, followed by a bold flourish on the violin that transitions into a delicate and subdued melodic phrase that leaves the listener breathless. The musicians are in the process of recording the composition, thus the sequence is played repeatedly and analyzed with meticulous attention to detail in order to make any necessary refinements.

It’s hard to imagine that the youthful Ukrainian orchestra, who play with such dedicated enthusiasm, waited in line for nine hours the day before to cross the Polish border. It’s also difficult to believe that they have been facing the harsh effects of a war for the past two years and that one of their horn players, Maryan Hadzetskyy, is currently missing in action.

The situation is extremely important for all those involved in the performance. The violin concerto was written by Thomas de Hartmann, a composer who is largely forgotten, and it is being recorded commercially for the first time since its debut in 1943 by the International Symphony Orchestra Lviv (INSO-Lviv). They will also be performing it in a concert featuring Ukrainian and Polish music in Warsaw. It is ironic that this revival is taking place during wartime, as De Hartmann’s score, which incorporates klezmer elements, was heavily influenced by the Nazi occupation of Ukraine and the persecution of its Jewish population.

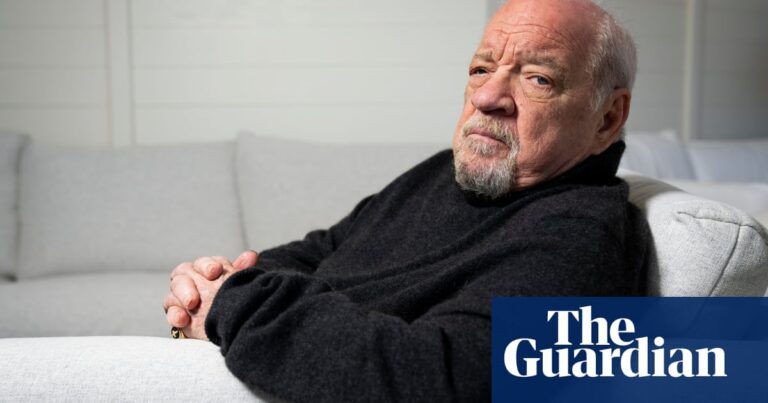

Bell is deeply enamored with his latest addition to his repertoire. He expresses to me, “This is truly a masterpiece of the 20th century.” He eagerly anticipates performing it alongside Stasevska and the New York Philharmonic, and even considers pairing it with the Barber concerto, which debuted a few years prior.

Bell expresses his admiration for the piece’s balance, particularly the intense and eerie finale following a unique, vignette-style movement that evokes imagery of a violinist wandering through the desolate Ukrainian steppes, performing his haunting and mournful melodies. De Hartmann’s wife Olga previously described the movement in this way. Bell describes the work as having a vivid, almost cinematic quality, with a tendency to transition between musical scenes.

Indeed, in the course of his extraordinarily eventful life – which took him from north-eastern Ukraine to study with Rimsky-Korsakov in pre-revolutionary St Petersburg, to Munich and a friendship with Kandinsky, to a life-changing wartime meeting with the mystic and spiritual leader George Gurdjieff, to Tbilisi in the 1920s, to Paris during the second world war, and eventually to the US where he died in 1956 – De Hartmann also wrote film scores.

According to Bell, the piece has achieved the feat of being easily approachable. It boasts of alluring melodies while also being highly captivating due to its intricate and unconventional harmonies. The piece is filled with unexpected elements, constantly keeping the listener on their toes. It defies expectations and this is a characteristic shared by all exceptional music.

But for the orchestra and Finnish-Ukrainian conductor Stasevska, there is a significant factor beyond just uncovering what she believes to be an overlooked masterpiece. The piece, along with other Ukrainian compositions that the orchestra is preparing to play in Warsaw, stands as a revelation and declaration of the country’s classical musical legacy that is currently being recognized in light of Russia’s invasion.

In 2022, I had the opportunity to meet Stasevska while she was leading INSO-Lviv in their hometown of western Ukraine. This was a unique occasion where a conductor from outside the country came to collaborate with Ukrainian musicians. Despite the recent lightning counter-attack in September, there was a sense of hope and positivity in the air. The Philharmonic Hall in Lviv was filled with boxes of much-needed medicine and supplies for those on the frontline. Stasevska and her two younger brothers had raised funds and personally delivered a truckload of humanitarian aid from Finland.

The musical event that evening showcased pieces from mostly contemporary Ukrainian composers such as Yevhen Stankovych, Valentin Silvestrov, and Bohdana Frolyak, and was met with enthusiastic acclaim. This was the first time the orchestra had played many of these pieces. Olena Kravets, the first violinist, recalls, “We did perform Ukrainian music prior to the war, but it was a more common selection. Now, our repertoire is expanding significantly.”

Stasevska was born in Kyiv and later relocated to Estonia at a young age. Her family escaped the Soviet Union to Finland when she was five years old, with only the clothes on their backs. Despite this, her father and grandmother preserved their Ukrainian heritage by immersing her in their culture, including reading Gogol stories, singing folk songs, and speaking Ukrainian at home. She notes that the De Hartmann concerto contains melodies that resemble familiar folk songs to her.

She initially pursued the study of violin and later viola at the Sibelius Academy in Finland. However, her perspective shifted when she witnessed a woman conducting for the first time. It occurred to her that her intense focus on reading scores and her belief in the symphony orchestra as “the greatest musical instrument created by humankind” could lead to a career as a conductor. When she first held a baton and joined the masterclass of renowned Finnish conducting professor Jorma Panula, it was the most exhilarating experience she had ever had.

Currently 39 years old and caring for her three-month old infant as we speak, her professional life is thriving. In the United Kingdom, she is recognized as the dynamic guest conductor for the BBC Symphony Orchestra who directed the opening night of the Proms in the previous year. In the United States, she was honored as a 2023 standout by the New York Times. In her home country of Finland, she holds the position of chief conductor for the Lahti Symphony Orchestra.

While organizing the October 2022 concert, she considered the significance of Sibelius as a representation of her adoptive country, drawing from her Finnish heritage. She acknowledged the deep impact of works like his overture Finlandia during challenging times when words fail to convey emotions, stating that music has the ability to connect with everyone.

Skip over the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

In a situation where Vladimir Putin has openly portrayed the invasion of Ukraine as a battle for cultural and national identity, Stasevska felt a pressing desire to shed light on a partially hidden Ukrainian music history that is waiting to be uncovered – despite the significant harm inflicted upon it by the Russkiy mir (the Russian cultural and political space) over many years: the Ukrainian composers who were imprisoned in the gulag, those whose musical compositions were never published, and those whose music was destroyed or lost.

She informs me about Vasyl Barvinsky, who was imprisoned for ten years from 1948. His musical compositions were destroyed in the backyard of the Lviv Philharmonic Hall. After his release, he dedicated the last five years of his life to reconstructing his lost music. He believed that as long as Ukrainian music was still being played, it could not be completely destroyed.

Currently, Ukrainian orchestras are not playing any Russian classical music. According to Kravets, a violinist in the orchestra, the last concert by INSO-Lviv before the invasion featured Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade and a Tchaikovsky symphony. However, she says she doesn’t miss these composers because there is a wealth of Ukrainian music that deserves recognition.

Ukrainian musicians talk about the damage done not only by direct suppression of composers under the Soviets, but by the assumption that truly great art emanated from only the imperial centre, from Moscow and St Petersburg. “Peripheral” Ukraine was regarded as the home of a folky, homespun culture that was essentially inferior. Or else Ukraine’s greatest artists – for example painters Kazimir Malevich and Ilya Repin – were absorbed by the centre and generally referred to as “Russian”.

One may question if De Hartmann, a musician born in Ukraine and trained in St Petersburg, was truly more or less Ukrainian than other composers like Prokofiev, who is often seen as Russian despite being born in Ukraine’s Donetsk region, or Stravinsky, who had Cossack ancestry.

Kravets acknowledges that the question is complex. She proposes that De Hartmann’s Ukrainian heritage be considered before the influence of the Russians, as was the case with other composers. Bell is cautious and does not want De Hartmann to be categorized solely as a “Ukrainian” composer, fearing that it could marginalize his work.

These inquiries are intricate and individual identity cannot be defined by one aspect. I reflect on Sergei Parajanov, the renowned director from the Soviet era who created films such as The Colour of Pomegranates. He once stated, “I am an Armenian, born in Tbilisi, imprisoned in a Russian jail for being a Ukrainian nationalist.” However, these are the struggles that Ukraine is facing amidst a frightening existential invasion. The intense focus on the question of Ukrainian identity – manifested through opinions on language and history, literature, art, and music – is a paradoxical result of Putin’s attempt to claim and assimilate the country. The consequences of this will be revealed in the months and years to come.

In the meantime, the power of works such as De Hartmann’s violin concerto is irresistible. As the war casts its grim shadow ever more deeply, Stasevska says: “There’s such a contrast between light and dark in Ukraine. Music is to me the light. It makes me believe in good – and in humanity.”

Source: theguardian.com