A

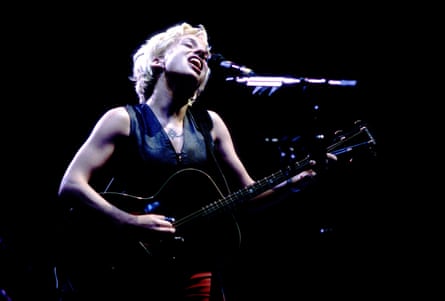

A change is occurring in the music industry as a new wave of female artists, inspired by Taylor Swift, are taking control of their music rights and rejecting contracts that give music companies total power.

Swift is close to completing her project of re-recording her first six albums, which were originally released under Big Machine Records. This is her way of showcasing her belief that the original albums were taken from her without her consent, and she sees it as a form of creative and commercial revenge. Her battle for ownership of her music extended to her 2018 contract with Republic Records, a part of Universal Music Group (UMG). One non-negotiable condition was that she would own the master recordings of her future albums and license them to the label.

This is a template used by emerging artists, particularly female pop stars who have historically been exploited in the music industry, as a way to gain control over their recordings and songwriting. Olivia Rodrigo, inspired by Taylor Swift, made it a requirement to own her masters when signing with Geffen Records (a part of UMG) in 2020. In 2022, Zara Larsson reclaimed her music catalogue and established her own label, Sommer House. Similarly, in November 2023, Dua Lipa gained ownership of her publishing rights from TaP Music Publishing, a division of the management company she left in early 2022.

During her performance at Glastonbury last summer, Rina Sawayama indirectly criticized Matty Healy from the band 1975 for his involvement in a podcast where racist comments were made. She also called out Healy for having ownership of her music masters through his position as a director at Dirty Hit Limited (although he was no longer a director as of April 2023). This claim overlooks the complexities of contract law, as Sawayama likely signed over the rights to her recordings in exchange for financial investment from the label. However, emotionally, it resonates with a fanbase that views “the industry” as the enemy of artistic expression and autonomy. Brian Message, a partner at Courtyard Management, believes that artists should have emotional ownership of their works, as they are the creators.

The changing dynamic between artists and labels can be attributed to the growing accessibility of information regarding complex music contract law. In the early 2000s, this type of knowledge was limited to specialized publications like Billboard, Music Week, Music & Copyright, and books such as Donald S Passman’s. However, today, discussions about industry matters are happening in mainstream media and artists have the ability to voice complaints and expose unfair contract terms through social media. A recent example of this is musician Raye publicly criticizing her label, Polydor, for preventing her from releasing her first solo album. After being released from her contract, she independently released her debut album, My 21st Century Blues, in 2023 to critical acclaim.

In today’s music industry, artists are more knowledgeable about the mistakes and traps of the past because they have to be. Many older musicians, like George Michael and Prince, had to sue over what they saw as being taken advantage of or mistreated. Others, like Radiohead, have prioritized retaining ownership of their rights in contract renegotiations for both economic and ethical reasons. Some artists were lucky to have insightful managers on their side, such as Bono who shared in his memoirs that their manager negotiated for U2 to receive a lower advance and royalties in exchange for regaining ownership of their recordings after a certain period of time.

The stories of Prince and George Michael serve as cautionary tales from the past, but the actions taken by Swift, Rodrigo, and others can serve as guides for the future. This also means that the music industry has had to adjust its practices away from contracts that center around ownership. There are two types of rights that are at stake: the rights to an artist’s master recordings and the rights to their songwriting, also known as publishing. A high-level executive in the music publishing industry explains that their sector was ahead of the game, as publishing deals now typically operate on terms of exclusive licensing or retention periods. They state, “Publishers have shifted from focusing on owning rights to managing them.” These retention periods have also become shorter, decreasing from approximately 25 years three decades ago to 12-15 years in present times.

According to the CEO of the Featured Artists Coalition, David Martin, many artists have a desire to own their rights. However, there are still some artists who are willing to give up ownership in hopes of achieving success. Martin notes that there are members of the coalition who continue to sign deals with major labels, but he cautions them to carefully consider the terms of these agreements.

The statement explains that the speaker avoids recommending contracts that are based on ownership. They have a policy of advising artists to avoid life-of-copyright deals, but they may consider them if necessary. However, their main suggestion is for artists to consider a licensing agreement instead.

The core belief behind BMG and AWAL (Artists Without a Label), which is currently owned by Sony Music Entertainment, is to change the traditional dynamic between artists and labels. Alistair Norbury, BMG UK’s president of repertoire and marketing, explains, “We wanted to create a more equitable and open way of collaborating with the creative community.”

Acts on BMG’s roster – notably Kylie Minogue, Suede, Sigur Rós and Louis Tomlinson – are on licensing or assignment deals, so ownership of the recordings eventually reverts to them. “They want to be with a record label where they have creative control and ownership coming back to them at some point,” says Norbury.

AWAL follows a similar philosophy. According to Paul Hitchman, the global COO of the company, AWAL was created to support independent artists in maintaining their independence. This means artists can own their rights and have control over their career, while still having access to expert support and without sacrificing global success.

According to Norbury, as the number of options for performances increases, music companies must consistently demonstrate their value and prioritize mutually beneficial agreements instead of one-sided deals that solely benefit the company. He suggests aiming for long-term success through partnerships rather than claiming ownership of something that ultimately fails.

Given the current circumstances, major record labels are being forced to provide more adaptable contract conditions. They are also making significant investments in additional companies that offer services for artists and labels, in order to benefit from the rise of DIY and independent musicians. For example, Sony owns Awal and the Orchard, UMG has Virgin Music Label & Artist Services and Ingrooves, and Warner Music Group has Ada.

Bypass the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

Stormzy is likely the most accomplished graduate of this method, as his Merky label has flourished under Ada’s guidance. In 2020, he also joined forces with 0207 Def Jam, a division of UMG UK. However, in his 2022 song “Mel Made Me Do It,” he proudly proclaimed “I possess all my master recordings, I am not controlled by anyone.”

In order to remain competitive, traditional record labels must explore alternative structures or agreements that are more favorable to artists, according to Erin M Jacobson, a music lawyer from the United States. She notes that independent labels typically have more equal rights compared to major labels. “Certain independent labels take pride in offering artist-friendly terms that are not commonly provided by other companies,” she adds.

According to Cliff Fluet, a partner at Lewis Silkin legal firm, he is not as impressed with the glamour of independent companies. Fluet explains that while many indies may offer seemingly fair 50/50 deals, it’s important to consider what exactly that 50% entails. He also brings up past instances where indie companies have faced issues surrounding ownership, exploitation, and digital royalties. Although he does not specifically mention it, the recent legal dispute between Domino Records and Four Tet, in which Kieran Hebden resolved a disagreement over past royalty rates with the label, serves as an example of this.

Fluet strongly believes that major labels continue to play a crucial role in launching new artists on a global scale. Despite what others may say about the decline of labels, he disagrees and argues that every successful global artist has had the support of a major label.

For artists who have been burned by previous label deals and have given up ownership of their original recordings, Taylor Swift’s re-recordings have proven to be a successful workaround. However, labels are becoming more aware of this tactic. While artists like Simply Red, Def Leppard, and Squeeze have also attempted it, they have not achieved the same level of success as Swift. According to a report by Billboard in October 2023, major labels are now including clauses in contracts that prevent artists from re-recording their tracks for up to 30 years.

According to Jacobson, clauses regarding re-recordings are becoming increasingly lengthy. She explains that this is due to the fact that re-recordings create competition for the label’s assets and potential income. The label does not want their product to be replaced by another artist’s version.

Fluet cautions against assuming that Swift’s approach is applicable to all situations. He states, “Including re-recording clauses in agreements is not a novel concept.” He adds that in his experience with major labels, such clauses are typically included for a period of five to 25 years. Fluet believes that the success of Swift’s re-recordings is unique to her and not likely to cause concern for most UK companies.

The head music publisher explains that re-recordings are often negotiated in synchronization agreements when artists want a larger portion of the payment. However, they warn that altered versions may not measure up to the quality of the originals. They express concern for the unique circumstances and imperfections that contributed to the creation of the original recordings, such as a singer’s sore throat or technical issues in the studio.

The landscape of the music industry has drastically changed over the last ten years, with emerging artists becoming more assertive in their demands. While not all new artists are able to negotiate from a position of power, they may have an advantage by tapping into the limited understanding of industry matters among today’s young pop fans. This can enable them to improve their bargaining positions by publicly calling out unfair actions taken by music companies. The previous era of compliance is now being challenged in this escalating fight for control.

Source: theguardian.com