T

The highly anticipated Christmas movie of 2023 has finally arrived, but it’s fashionably late – much like a tipsy party-goer who has lost track of time. The Holdovers is a gritty drama that takes place in a deserted boys’ boarding school, centering around a forlorn Norwegian spruce tree. The message of holiday cheer, if you can call it that, is delivered by Paul Giamatti in his role as a grumpy teacher of classical studies. “I see the world as a harsh and complex place,” he proclaims. “And it seems to feel the same way about me.”

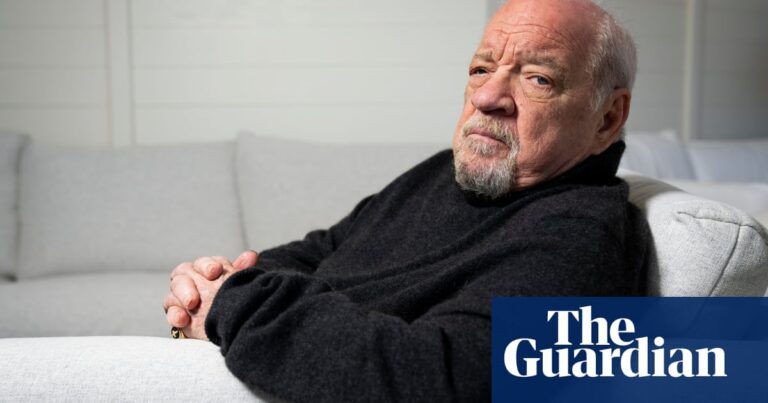

Alexander Payne, the director of the movie, The Holdovers, has experienced some lonely Christmases in the past, but his 60th birthday during the COVID-19 pandemic was particularly isolated. He recalls having to isolate himself due to being infected with the virus and spending the day alone in his apartment. However, he acknowledges that it could have been much worse and is grateful for friends who brought him food and left it outside his door.

Events of misfortune, hardship, and acts of benevolence: these are the ideas that resonate with Payne as a director. These are the conflicting elements that drive his most successful films, such as the Academy Award-winning Sideways in 2004 (which follows a struggling writer, played by Giamatti, on a journey through California’s wine country) or Nebraska in 2013 (where a broken Bruce Dern chases the American dream). The mood can be unpredictable; the emotional atmosphere constantly changes.

The way Payne prefers it is similar – it keeps the viewers engaged. “There is a Greek term for this: harmolipi,” he explains. “It represents a mixture of happiness and sadness. In Greece, the two masks were always paired together. ‘Bittersweet’ is probably the most fitting term in English.”

Our interview just began, but it feels as if we are already in a classroom at The Holdovers’ Barton Academy. The director carries himself like a scholarly wolf, exuding confidence and precision. He is well-versed in film history and has no problem dismissing amateurs. “I like to think of my films as comedies,” he introduces himself. “John Ford used to say, ‘I’m John Ford and I make westerns.’ I say, ‘I’m Alexander Payne and I make comedies,’ because even when dealing with serious subject matter, I strive to maintain a comedic perspective. Keep it light, keep it charming. But that’s just life, isn’t it? It may sound cliché, but life is not just one note, it’s a combination of chords – minor and major keys, happy and sad moments.”

The movie, The Holdovers, has been widely praised and is considered a top contender for an Oscar. It has also been chosen by Barack Obama as one of his favorite films of the year. The story follows Paul Hunham, played by Giamatti, a cynical man stuck at Barton Academy during Christmas break. He forms an unusual makeshift family with the school’s grieving cook, Da’Vine Joy Randolph, and a troubled student, Dominic Sessa. At the start, Hunham acknowledges that none of them want to be there, setting the stage for the film’s conflict. However, as the winter passes, the characters’ broken pieces come together to form a whole. Like Payne’s 60th birthday, this holiday may not be a lost cause after all.

Fittingly for a film about misfits in limbo, The Holdovers is also bloody-mindedly out of step with the times. It’s not so much that the tale relocates Payne from his favoured pancake-flat midwest to a snowbound Massachusetts of melancholic mill towns and white-water rivers. It’s not even that his Christmas movie seems to have been delayed in the post. It’s simply that The Holdovers is in thrall to the bygone 70s era of American film-making, to the point where it moves beyond homage or pastiche.

The 1970s have a strong presence in the picture, resembling the lettering in Brighton rock. The influence is seen in the setting, which takes place in December 1970, the technique used (slow pans and dissolves), and the emotional impact of the plot (alternating between gritty and sentimental).

According to Payne, the print is marked with a 1971 date in order to create the illusion that it was filmed in 1970 and then released the following year. This gives the impression that the film is a relic from the past, possibly still carrying scents of patchouli oil and cigarettes. Payne suggests that our choice of this particular date may have been unconscious, but it ties in with the themes of the film as a whole – a sense of uncertainty and loss of direction in the country. Additionally, there may be a rebellious element to the film that reflects current events. How do these elements relate to or comment on our current situation?

I am certain that they do, but I believe that the movie can stand on its own. The industry has evolved and movies now have a faster pace. In other words, how many traditional American films does Payne foresee being made currently?

“Let’s consider this together,” the director suggests, settling back into teaching mode. “When it comes to comedy, where are films like Groundhog Day or Trading Places nowadays? Where can we find a solidly constructed, clever comedy-drama? And what about visually sweeping adult dramas like Terms of Endearment or Out of Africa? My concern is that nowadays, it’s mostly just Marvel movies or nothing. It seems that if your film doesn’t involve flying superheroes, it’s unlikely to receive funding.”

Payne’s destiny was to enter during the final phase of the era he admires, riding the last wave of 70s-style auteurist cinema commonly referred to as the 90s indie scene. He achieved success with the perfectly executed film, Election, which pits a distressed teacher, played by Matthew Broderick, against a nightmarish student, played by Reese Witherspoon. He then continued his streak by featuring possibly the last remarkable performance by Jack Nicholson in 2002’s About Schmidt.

Since then, it has been challenging; every movie has been a struggle. “Nebraska, specifically, was difficult to secure funding for because I insisted on filming it in black and white. Even at $14 million, which is a small amount for people in the industry, it was still a challenge to get it made. The Descendants was easier because I had George Clooney on board – he was a big, shiny attraction. And Downsizing was a different story, with a larger budget and the added bonus of having Matt Damon attached. On paper, Downsizing looked very promising.”

I must admit, I enjoyed Downsizing. However, it was not well received by many others. The 2017 sci-fi comedy from Payne was overly ambitious and unpredictable, ultimately causing its downfall with critics and at the box office. While he has managed to persevere through the backlash, it was a tough moment: “You can’t dwell on it, you have to keep moving forward.” He reflects on past film failures, referencing Brian De Palma’s quote about how it’s almost a rite of passage in Hollywood to have a film flop.

Ignore the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

Payne grew up in Omaha, Nebraska, in a Greek-American household with two older brothers. As a child, he disliked the city’s conservative atmosphere and eagerly looked forward to leaving. However, Omaha ultimately played a crucial role in shaping his filmmaking style and serves as a strong presence in many of his works. Although some might consider it a character in itself, Payne dismisses this idea. He compares it to failing an exam and remarks, “The idea of landscape as a character is quite overused.”

Currently, he has a residence in Los Angeles and a home base in his hometown. He shares that Omaha has undergone changes, becoming more progressive and hip. However, one of the main reasons he resides there is for his family. His father has passed away, both of his brothers are also no longer living, and his mother just celebrated her 100th birthday. As a result, it has become his responsibility to closely care for her.

After finishing The Holdovers, Payne is currently unemployed. He has expressed interest in making a sequel to Election, with Witherspoon reprising her role, but the script requires some adjustments. Another option is to use his Greek passport and create a film in Europe. Regardless of which path he chooses, it will most likely be another tragicomedy, centered around individuals who are marginalized, discontented, and struggling to make ends meet.

“Payne acknowledges the irony. He confesses that the films he enjoys the most – those with true depth – center around the marginalized and impoverished. However, these films are created by directors who, in societal standards, have achieved great success at the highest level.”

I inquired if he was also included. He flinches at the assumption. He responds: “I am nothing in comparison to Charlie Chaplin. And he portrayed a character who was homeless.”

Does he view himself as a successful individual?

“Jesus,” he says, all but throwing up his hands. “I guess you really did run out of questions.”

Except that school is not quite out; we still have a few minutes left. “This is going to be a real downer of an answer, but I recently had a brother die of pancreatic cancer,” says Payne. “Watching him go through that process gave me a fine perspective. Anything you go through in life, trust me, you’re in pretty good shape if you don’t have pancreatic cancer.”

He pauses and reflects. “Can I offer a more positive response?” he suggests. “I am extremely fortunate to have a career in filmmaking. I consider myself lucky to have been born during a time when movies were a form of entertainment. I am grateful to have developed a passion for them and to have had the opportunity to make films and achieve some level of success. Overall, I feel very accomplished in that sense. As I continue to age, my sense of gratitude and luck only grows. This is just how life goes, isn’t it?”

Source: theguardian.com