In 2019, a year after his band Wild Beasts had split, Tom Fleming toured his debut solo album as One True Pairing. It was, by his account, a “fucking awful” experience, with only a couple of well-attended shows. “It was really difficult,” he admits. “Putting Wild Beasts on tour was like putting an army in motion. I wanted to go back to basics. But even then, it was obvious: this is not right and I’m not in any fit state.”

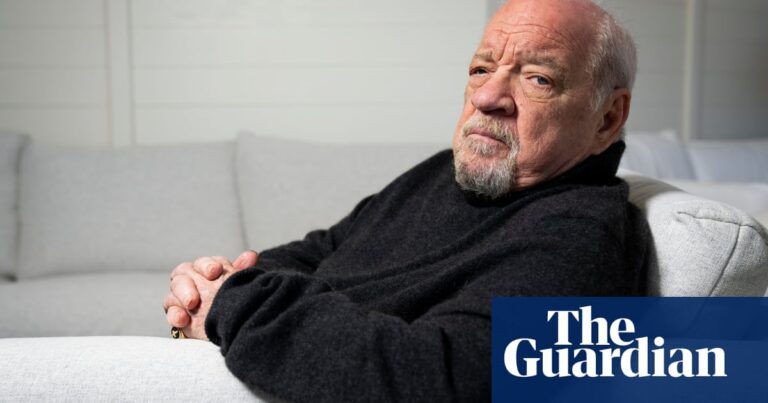

The baroque Kendal four-piece had gone out on a high after five brilliant albums, two of which hit the UK Top 10, three glorious farewell gigs, no animosity – they’re still friends – although Fleming, who was the gruff vocal foil to the more florid Hayden Thorpe, wanted to continue. “If one person doesn’t want to be there, you haven’t got a quartet any more, so I think it was the right thing to do,” he says in his beautifully deep Cumbrian accent, drinking the day’s umpteenth black coffee on a warm October afternoon near Waterloo.

He had no plan B, having only known band life since his teens. “I loved everything about it and it felt as if I left something of myself on the stage every time we played. But it’s also bad for your sanity – the travel; I had a huge problem with drinking. Where everyone else would stop, I was the last one standing. I’ve had diabetes since I was nine. I was playing with fire, really, and starting to have problems with my eyesight, circulatory problems, despite being otherwise in good shape,” he says, affable and matter-of-fact. “Hitting your mid-30s, it was like, I’m not young any more and that sort of invincibility starts to thin.”

Speaking of which, he apologises, it’s time for his insulin. He lifts his black vest and injects without flinching. Despite the warning signs, he immediately launched a solo career (as did Thorpe, although guitarist Ben Little and drummer Chris Talbot have left music). The eponymous One True Pairing album was a synth-pop take on brawny US heartland rock, and an acerbic takedown of limited perceptions of the working-class culture Fleming had grown up in, as well as the cycles of violence and oblivion that culture can perpetuate. “It probably sold about 50 copies,” he says.

Come 2020, Fleming’s life was in disarray. The breakup of a long relationship – “partly through my own behaviour” – left him homeless. He moved back in with family and caught first-wave Covid. The pandemic quashed his fledgling solo career, though he was eligible for government support and began working as a copywriter: “I spent a long time sulking and didn’t quite get back to normal for a long time,” he says.

It sounds a bit more serious than sulking. “It was a bit of a breakdown, to be honest,” he admits. “Confronting your own vulnerability is difficult. No matter how much I tell myself I wasn’t hiding it, I was.” His new record “comes hand in hand with that”.

Endless Rain, the second One True Pairing album, is as miraculous a return to form as anyone has ever made. Fleming recorded it in 2022 with Lankum producer John “Spud” Murphy, near Dublin, the electronics and US heartland stuff replaced by heavy, hymnal folk that feels lashed with saltwater, thick with earth, possessed of a thousand-yard stare into the dark of night. The voice that used to fire a rocket up your middle in Wild Beasts now seems to resonate within the belly of a vast ship. It’s beautiful: melodic, profound and raw.

Now 39, Fleming has often talked about how embarrassing he found the idea of making singer-songwriter music. He had to get over it because these songs were so much more vulnerable. “I went back to being 16, to the source – what do I like? I’ve had an elegant moment to retire and I haven’t done it, so it became about deepening my love of stuff rather than finding the next new thing.” He had “hugely” lost confidence. “You’re in danger of following everything when you don’t have the confidence.”

Fleming hopes that listeners will recognise the difference between an “earnest singer-songwriter, Jack Johnson-esque thing” and him channelling the American primitive guitar and new weird Americana he loved as a teenager, music whose “endless mystery you can pull with very few colours on the palette. Trusting yourself to do that is really hard.”

Although his lyrics are poetic – lost souls teem in the rising flood water he witnessed in Cumbria in 2020 and ghosts haunt the supermarket aisles of his youth – Endless Rain is otherwise strikingly plainspoken about human frailty, doubt, depression. Fleming’s consciously written lyrics sounded contrived when he recorded them; his extemporised phone memos were the most convincing. “And here it comes again / Those old dark jaws / Clamping round my legs,” he sings on I Don’t Want to Do This Anymore. At times, he felt he had ended up somewhere he might not come back from. “Definitely staring at the void,” he says, hence the direct writing. “I’m sick of trying to be clever. I was looking for something that would connect because my number-one thing is being understood.”

Fleming lives in Surrey with his partner, Jenny, who he credits with giving him “a stern kick in the ass” that helped him address the drinking and mental health issues he had been denying. “It was a huge relief,” he says. “OK: we can stop pretending now.” He has been sober 18 months and recently got an autism diagnosis; he still works as a copywriter and currently only has one live date planned around the new album: “I don’t want to be thrashing myself.”

Committing to recovery also meant changing his attitude to mental health, which he had been “quite sniffy” about in the past. “I saw it as a middle-class indulgence. In some ways it is – therapy is expensive,” he says. He also laments tidy “self-actualisation narratives” of recovery. “I think it’s important to say that [mental health] has a really unflattering side and you can be really horrible to be around when you have those sorts of episodes.”

On Fleming’s pugnacious debut solo album, he lashed out at the world, pessimistic and angry. Endless Rain is arguably darker, but more compassionate and hopeful. He calls it his “first grownup record”, and a reckoning – “with mortality, or what you become and what you haven’t become. I saw friends having not just children, but several children, and not buying a house but buying their second, bigger house. Where did I go wrong? I’d had quite a successful life by a lot of accounts, but it’s like, Jesus, I’m holding nothing here – just a whole string of failure.” Wild Beasts “surfed the decline of the music industry, we were the canaries in the coalmine … None of us made enough money to put a deposit down on a house in London. But I did those things for a reason. I don’t regret it.”

after newsletter promotion

Those reflections prompted him to look back further. Frozen Food Centre, a seven-minute swell of fingerpicked guitar, cello and harp, centres a vignette of him aged seven, called into school with his mother to discuss his “violent behaviour”. He had broken a boy’s nose. “I was being bullied and I hurt him quite badly,” he winces. The incident was cleared up – Fleming was a well-behaved kid who had just reached his limit. “But being a sensitive person capable of violence – that is all throughout my stuff,” he says. “That’s important, talking about healthy masculinity – don’t feel bad for being like that. Some people will test you and try to make you a victim for your vulnerability.”

Fleming’s first solo album also satirised what he saw as “commodified” discourse about toxic masculinity, with lacerating lyrical portraits of blokes who “took out a loan and smashed the whole thing in Ibiza”; boys he grew up around with a “collection of knives and the porn printed in black and white”. Endless Rain takes a more tender, insular look at how expectations of masculinity had left him feeling insufficient. “The world can be quite a cruel place,” he says. “It isn’t a place where you can feel good about expressing your emotions because you’ll get minced.” That fear, he thinks, is how toxic defence mechanisms can develop. “Even my knowing better – and having quite positive male role models – I’ve still embodied a lot of that: that rage, that internalised machismo, not to the world but to myself.”

And the bigger picture of Endless Rain feels like one of how society is set up to exploit and isolate people: Fleming sings about ruthlessness, carelessly tossed-up housing estates; he wonders if the current cultural attraction to folk music and culture that this album reflects is a response to what “a horrible influence the digital, online world has had on the real world”.

A Landlord’s Death is an unvarnished revenge fantasy and the album’s only moment of glee: “We will drag you meekly from your beds,” he sings to vigorous, rallying strums. “I grew up in rented accommodation my whole life and never had someone to give me a [house] deposit,” he says. “I’ve been a northerner adrift, and certainly, my experience in the music industry, [around] these awful lizard people, it’s enraging: you have people talking to you about white privilege as if you’re the same as them. It’s mind-blowing. That song is my cheeky, snarky little kickback.”

Either way, the necessity of collective action shines through. Endless Rain ends on the line “we all rely on each other”, on The World Said No, “because I spent a long time feeling isolated and alone,” says Fleming. “You realise that you’re not that, that your connections with people matter. The world is not cold and dead.” That feeling drove him to finish writing a difficult album. “When the money dries up, it’s like, ‘What am I doing here, what do I actually care about?’ This story is actually what I care about.”

Source: theguardian.com