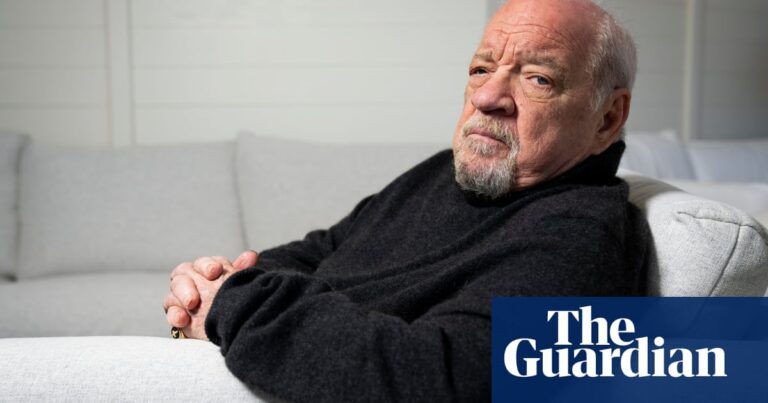

XVIII. Caesar and Cleopatra (1945)

In this heavy-going British Technicolor adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s play, Claude Rains’s oddly relaxed Julius Caesar plays father figure to Vivien Leigh’s implausibly girlish Cleopatra, schooling her in the art of power with just a hint of May to December flirtation. The two leads are just about charismatic enough to compel interest despite Shaw’s ponderous dialogue.

XVII. A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966)

Stephen Sondheim’s hit Broadway show based on the comedies of Plautus gets a big-screen transfer boasting the talents of Zero Mostel, Phil Silvers, Michael Hordern, the young Michael Crawford – and Buster Keaton in his last film. It should be a riot, but it misfires: director Richard Lester drives the farce so hard it’s almost impossible to follow and inexplicably uses just five of Sondheim’s songs.

XVI. The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964)

This lugubrious box-office bomb, which killed off the Roman epic for decades, charts the transition from poisoned philosopher emperor Marcus Aurelius – Alec Guinness, phoning in the gravitas – to wayward son Commodus. Marches, processions and battles win out over narrative coherence, Sophia Loren and Stephen Boyd bring glamour without chemistry, while Christopher Plummer’s startling performance as the increasingly deranged Commodus gets lost in the mix.

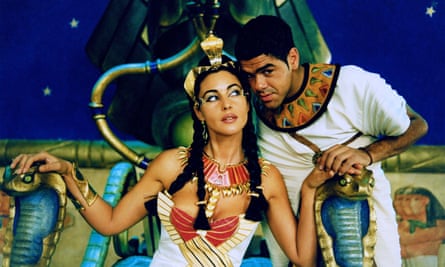

XV. Asterix & Obelix: Mission Cleopatra (2002)

The best of the five Asterix & Obelix live-action films (OK, not a high bar) sees the two moustachioed Gauls (played by Christian Clavier and Gérard Depardieu) help architect Edifis (Jamel Debbouze) build a palace for Cleopatra (Monica Bellucci). It’s amusing enough, but would doubtless be funnier if you can understand the wordplay in the original French. The only film here with a bespoke Snoop Dogg track over the end credits.

XIV. Sebastiane (1976)

Derek Jarman’s first feature (co-directed with Paul Humfress) follows Sebastian, former favourite of the emperor Diocletian and a devout Christian, on his exile to a military outpost seething with sexual tensions. A low-budget landmark of queer cinema, it also wins laurels for authenticity, being scripted entirely in Latin (the title is in the vocative case, in case you were wondering).

XIII. The Eagle (2011)

Roman officer Marcus (Channing Tatum) and British slave Esca (Jamie Bell) head north of Hadrian’s Wall to find the golden standard that was lost when Marcus’s father’s legion went missing 20 years earlier. All that stands in their way is a formidable tribe of Gaelic-speaking, blue-faced “Seal People”. Kevin Macdonald directs this somewhat predictable Romano-British western with a sure touch.

XII. Carry On Cleo (1964)

Everyone knows the “Infamy! Infamy!” line, but there’s a deeper reason why this outing of the Carry On franchise – filmed on sets originally made for Cleopatra – is probably the most fondly remembered: the cast, led by Kenneth Williams as a hapless, henpecked Caesar, are all fizzing at the top of their game, making it churlish to quibble about the uneven gag quality and a plot as flimsy as Amanda Barrie’s costumes.

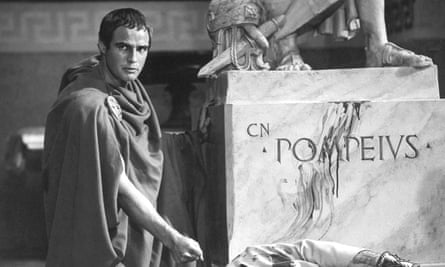

XI. Julius Caesar (1953)

Roman and biblical films took off in the 1950s as colour spectaculars with huge sets, but this black-and-white Shakespeare adaptation from MGM keeps it relatively simple, majoring on its superb cast: a red-hot Marlon Brando as Mark Antony, James Mason on strong form as Brutus, and a particularly lean and hungry John Gielgud as Cassius. Joseph L Mankiewicz directs, a decade before he took on Cleopatra.

X. Fellini Satyricon (1969)

Federico Fellini’s loose interpretation of Petronius’s Satyricon – a picaresque novel that survives only in fragments – is disjointed and bewildering, a visually astounding fever dream of ancient Rome. A film more to be admired than enjoyed, it reaches back across two millennia to present lurid, arresting snapshots of a strange pagan culture.

IX. Cleopatra (1934)

Claudette Colbert is kittenish and steely in Cecil B DeMille’s brisk run-through of the Cleopatra legend, from arrival by carpet to death by asp. Released just after Hollywood self-censorship came into force, the film still has a pre-Hays Code feel to it: the skimpy outfits, the on-barge party that breaks out after Cleopatra’s seduction of Mark Antony, and the sense that no one is taking it that seriously.

VIII. Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979)

Among its many virtues, Life of Brian is a splendid parody of a Roman epic, from Terry Gilliam’s bombastic opening titles to the unheroic chorus of “I’m Brian!” spoofing Spartacus. And you don’t have to have studied Latin to enjoy the names – “Incontinentia, Incontinentia Buttocks, Biggus Dickus” – or the “Romanes eunt domus” grammar lesson.

VII. The Sign of the Cross (1932)

Claudette Colbert bathing in donkey milk, an attempted lesbian seduction dance, a gorilla approaching a semi-naked woman tied to a post … it’s all there in Cecil B DeMille’s scandalous pre-Code romp about the crackdown ordered by Nero (the wonderful Charles Laughton) after the fire of Rome. Marcus Superbus (Fredric March) should be rounding up Christians but falls for one of them instead.

VI. Quo Vadis (1951)

Launching the postwar boom in Roman epics, director Mervyn LeRoy serves up a full-colour, cast-of-thousands spectacle made at Cinecittà studios. The plot is similar to The Sign of the Cross: Robert Taylor’s army officer is wooing Deborah Kerr’s clandestine Christian, while Nero (Peter Ustinov) warbles and dreams of burning Rome. There is memorable support from Patricia Laffan, exuding lizard-eyed menace as Nero’s wife Poppaea, and Leo Genn as the world-weary Petronius.

V. Caligula: the Ultimate Cut (2023)

Decried as a “moral holocaust” on its original release in 1979, Caligula emerges as a compelling portrait of unfettered power in this revelatory new cut, endorsed by star Malcolm McDowell. Stripped of the porn spliced in by producer Bob Guccione, but still bursting with nudity, depravity and gruesome violence, it now makes far more sense and allows extra screen time for Helen Mirren as the emperor’s wife, Caesonia. McDowell gives an electrifying performance to complete an unholy trinity with his roles in If … and A Clockwork Orange, while Peter O’Toole is convincingly repellent as the degenerate Tiberius. Influenced by Fellini Satyricon – designer Danilo Donati worked on both films – this disturbing film dares to show aspects of ancient Rome untouched by the classic-era epics.

IV. Cleopatra (1963)

Monumentally expensive and beset with production problems, this four-hour marathon became a symbol of epic bloat while entering legend for bringing Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton together. But viewed today with the benefit of a pause button, it’s a superbly enjoyable spectacle with intelligent dialogue that has plenty to say about the 18 momentous years of ancient history it covers. Rex Harrison’s thoughtful portrayal of Julius Caesar dominates the first half, while the second traces the sad descent of Mark Antony (Burton) into self-destructive passion and self-pity as he loses his power struggle with Octavian (Roddy McDowall). As Cleopatra, Taylor radiates megawatt star power throughout, right to the stunning final shot of her dead body laid out in gold.

III. Ben-Hur (1959)

The colossus that marked the apogee of epic – shot in widescreen and unfolding over three and a half hours – and won a record 11 Oscars (since matched but not beaten). To modern eyes, the overlap with the story of Jesus gets in the way of what should be the film’s essential storyline: the broken friendship and subsequent animosity between the Jewish patriot Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) and ruthlessly ambitious Roman commander Messala (Stephen Boyd), which comes to a head in the still-stunning chariot race. Haya Harareet as Judah’s beloved Esther and Jack Hawkins as the consul Arrius (“Battle speed … attack speed … ramming speed!”) offer terrific support. The gargantuan scale is really the point of it all – sit back and enjoy those grand sets and the ravishing Miklós Rózsa score.

II. Gladiator (2000)

Taking the basic scenario of The Fall of the Roman Empire and adding ingredients from other classics (the great man reduced to slavery of Ben-Hur; the fight school sequences of Spartacus; the arena scenes from Quo Vadis), director Ridley Scott resuscitated the long-dead Roman epic with this powerfully straightforward tale of betrayal and revenge. Russell Crowe is career-definingly immense as Maximus, fighting his way towards Joaquin Phoenix’s deliciously creepy Emperor Commodus. An excellent supporting cast – including Oliver Reed, who died during the shoot – adds to the film’s lustre. It may not have had much new to say about the grandeur that was Rome, but were we not entertained?

I. Spartacus (1960)

After failing to land the lead in Ben-Hur, Kirk Douglas became the star-producer of his own Roman epic, hiring the young Stanley Kubrick to direct. It’s not quite a masterpiece: Douglas is a little one-note as the eponymous leader of a slave revolt that is both underexplained and sentimentalised. But unlike many epics, the film proceeds with a sense of purpose, is packed with memorable scenes, and deserves credit for breaking free of the Christian sermonising that had marked Roman films of the 1950s. Nor does the thinly veiled modern political subtext in Dalton Trumbo’s script detract from this earnest portrait of a significant episode in Roman history. Laurence Olivier is magnificent as the brutal, haunted Crassus and Charles Laughton even better as his wily senatorial rival, Gracchus; Peter Ustinov picked up an Oscar for his turn as the slippery slave master, Batiatus.

Source: theguardian.com