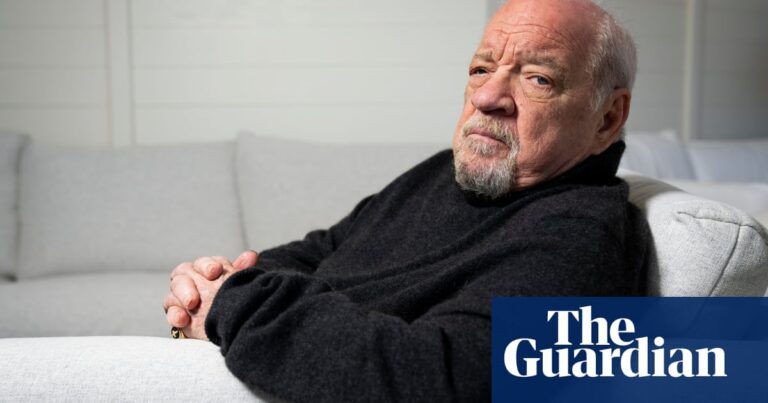

Renowned music producer Joe Boyd was the first production manager to plug Bob Dylan into an electric guitar, at the Newport folk festival in 1965. He remembers Pete Seeger walking away in disgust. When I interviewed Boyd half a century later, he said, to my surprise, that he had come to understand Seeger’s response. Boyd’s record collection was a clue as to why: expansively arranged in alphabetical order by country, far and wide. India, Indonesia, Iran…

Having produced Pink Floyd, Eric Clapton, Fairport Convention, Nick Drake etc, Boyd had turned his attention to music from over the horizon, derived from the rites and roots of those who make it. The culmination of Boyd’s lifelong journey in pursuit of such music is this vast volume, every paragraph packed with information and inspiration – but written with a refreshingly light touch.

Inasmuch as music is an expression of the human world – our aspirations, tribulations and celebrations – this is a history of that world, told through music. And although music may derive from heritage, it is by definition “sans frontières”, and the book explores “how rhythms, scales, and melodies flowed across the globe, constantly altering what the world danced and listened to”. Especially across the Atlantic Middle Passage: a binding thread explains how much great music was created in defiance of the brutal horrors of colonialism and slavery.

After Cuba became the fulcrum of the colonised Americas, “Afro-Cuban” music reverberated in all directions. The zaraband and chaconne, “branded as lascivious ‘Negro imports’ when first heard in Seville”, were “turned into polite templates suitable for Bach and Handel”. Later, in New Orleans, “multiple forces were coming together… to create the soundtrack to the first half of the western hemisphere’s 20th century”. European innovations based on harmonic experiment were confronted by polyrhythms new to them, but centuries old in Africa. What Europe called syncopation had forever been an African “way of perceiving time”. Boyd’s description of Dizzy Gillespie crossing that “rhythm chasm” is electrifying.

An inventory of musical instruments in Brazil is “almost as long” as that of the 134 responses to a census of 1976 asking people to define their skin colour. When the tradition of Carnival (carne vale – farewell meat, for Lent) began in the 1890s, “Brazilian authorities tried to keep a lid on Africans joining in too exuberantly”. Likewise the generals, when it came to Tropicália music after the coup of 1964: Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso were imprisoned, then fled to hang out in Notting Hill.

after newsletter promotion

There are “scales, melodies, rhythms, instruments and folk tales all swirling round in that mid-Atlantic gyre,” writes Boyd. He cites Nigerian wonder-drummer Tony Allen, after he heard bebop: “We should have been playing… like that in Nigeria. After all, it originally came from here. They took it, went to the Americas, polished it, and sent it back to us in Africa.” “The dialogue,” Boyd adds, “was almost entirely between Africans and their long-lost cousins, whose ancestors had been taken in chains from these same lands. Their descendants had propelled and provoked the ‘developed’ world into musical modernity; now it was Africa’s turn.”

Ravi Shankar’s music mastered Indian modal scales in which “the sequence of notes used while ascending always differs from those on the way down” and which are “not limited to what western music calls whole or semitones”. When they reached New York, John Coltrane inflected My Favorite Things with Indian modes and his epic India was “based on a Rajasthani folk melody”. Shankar captivated the west, met with George Harrison and Yehudi Menuhin, changing the lives of both, and music far beyond them.

A chapter exploring Russian and eastern European music finds Boyd at the Koprivshtitsa festival in Bulgaria: “a stunning spectacle: as far as I could see, there were woods and meadows filled with crowds in wildly colourful traditional garb. Eight stages were scattered across the plateau, each representing a different district.” But on Boyd’s return to Koprivshtitsa after the fall of communism, “wedding bands played a hybrid of simplified Serbian and Thracian beats at a deafening volume”.

The disappointment cues an important theme in Boyd’s thinking, post-Newport. Throughout the book, he is part of its story. And as writer and producer, he insists that music should be performed and heard with minimum technological conveyance. When producing the Bulgarian band Balkana, he convinces singers to gather around a single microphone, because “harmonies blend much better in the air than in a mixing board’s transistors”. During the book’s conclusion, meditating on how music informs memory, Boyd protests that “a computer-generated rhythm feels completely different from one created in real time by humans”.

Music in Boyd’s book is often a means of seduction, and at times sexual liberation from puritanism, mostly Protestant or Muslim. But carnal music, and music from the earth, also reach for the sublime: Boyd finds music expressing syncretism between religious beliefs – Afro-Cubans, Bahia Brazilians and slaves in the American south “finding convenient parallels between Christian Saints and their own Gods”, with effortless spirituality, but musical complexity.

Above all, this book is about music as deliverance from oppression. In South Africa, “with all attempts to ameliorate the harshness of white rule thwarted, music became the expression of African anger, hope, misery and joy… singing became the weapon of choice”. Boyd cites Hugh Masekela: “The government despised our joy.” Conversely, the USSR needed to destroy deep folk music precisely because it constituted peasant identity: “wood nymphs morphed into tractors… The Soviet solution was to drain every ounce of life out of musical forms they couldn’t comprehend.”

One of Veloso’s jailers told him “he considered the Tropicálistas’ deconstructions a far greater threat than any leftwing agitation”. “Exhibit A,” writes Boyd, “in the case for humanity’s resilience in the face of unimaginable horror, for its ability to create beauty in defiance of monstrosity, is the extraordinary sounds created by Congolese musicians even as their land was being plundered.”

Boyd’s book is, accordingly, the Proust of music history – à la recherche of much music lost, here regained and affirmed in our present.

Source: theguardian.com