“I thought I’d landed in a hippy cowtown,” says Michael Stipe, of his first months as an art student in Athens, Georgia. “I was an urban punk rocker, and Athens seemed beige and granola; it took me a while to find my ‘people’.” But, in 1979, at the only coffee joint still open after Stipe’s nightshift at the local steakhouse, he saw “this unbelievable, almost-cartoonish trio who looked like they’d stepped out of the Weimar Republic”, he says. “I waved at them. They waved back.”

That trio – Jeremy Ayers, Davey Stevenson and Dominique Amet – later became Limbo District, the most radical group of an Athens underground scene that gave the world the B-52s, Pylon and, of course, REM. But while those bands went on to enjoy global recognition, Limbo District are forgotten. They existed for only two years, imploding messily before releasing any music. For decades, the only evidence they ever existed was several minutes’ footage in 1987 documentary Athens, GA: Inside/Out.

“They were one of the greatest bands on Earth,” says Stipe. Now a new album of rediscovered live recordings illuminates a group whose fusion of art, furious rhythms and punk sensibility proved an indelible inspiration to Athens’ future stars.

Limbo District were led by Athens-native Ayers, the son of a professor of religion and philosophy at the University of Georgia. “Jeremy Ayers inspired almost every musician in Athens,” adds Keith Strickland of the B-52s. “His early-70s parties were like art happenings – walls covered with black plastic; floors thick with popcorn; Beefheart and Velvets records playing. He opened doors to creative possibilities. Plus, Jeremy and his boyfriend Chris [Coker] were gay – so were Ricky [Wilson, future B-52s guitarist] and I, but we weren’t out yet. It was inspiring to see Jeremy walk around Athens in tight velvet pants and a little fur coat.”

Ayers loved recording himself reciting poetry and playing percussion while Chris improvised on recorder. Strickland says: “It was a cacophony, and it was the introduction to writing and recording for Ricky and me. We continued that method of songwriting.”

In 1972 Ayers escaped to New York, joining Andy Warhol’s Factory studio, writing for Interview magazine as Sylva Thinn and befriending superstars such as actors Holly Woodlawn and Jackie Curtis. “Andy loved Jeremy,” says Stipe, “and Andy was hard to impress.” But within two years, Ayers returned.

“There was a cynicism to that scene, a hard edge,” says Strickland. “Jeremy wanted a different life.”

Athens was certainly different: it had no clubs, no “real” music scene. Bands in Athens played house parties to entertain their friends; careerism wasn’t a prospect – although REM would, of course, go on to global stardom. Even here, Ayers’ influence was key.

“Jeremy was a great friend and mentor,” Stipe says. “The person that I became, the public persona of Michael Stipe, I owe to him. He taught me how to dance, how to laugh at myself, how to dress. At the time I thought he was the first love of my life – although it turns out I was just infatuated with him,” Stipe laughs.

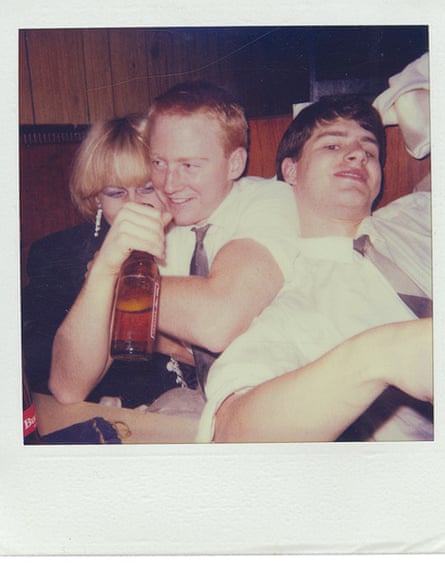

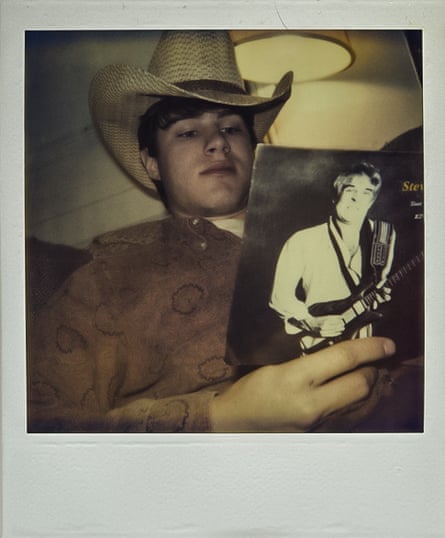

Ayers formed Limbo District in 1981, playing percussion. His boyfriend, Stevenson – “a big, buff, beautiful redhead who loved to discuss Schopenhauer”, says guitarist Kelly Crow, who went on to become a band member – played bass. Amet, who played organ, was from an upper-class French family and knew nothing of rock’n’roll.

“At their first rehearsals Jeremy asked her to sing Johnny B Goode, and she sang like it was opera,” says Crow. “Jeremy loved that: he’d been hoping for someone who didn’t come from a [typical] western music background.”

Amet was “Amy Winehouse levels of exotic”, adds Stipe. “She’d strike matches and use the ash as eyeliner, applied with a nine-penny nail.”

Singer Craig Woodall was “a small, quiet guy from a place where you couldn’t be outwardly queer and not expect something to happen to you”, remembers Crow.

“Craig had a very hard life,” adds guitarist Margarita Bilbão, an émigré from Basque Spain they discovered after hearing her rant against Athens on student radio. She’d never played guitar before, but the band loved her attitude, and that was more important. “I hadn’t had any friends in Athens,” Bilbão remembers. “Those guys became my saviours.”

Even among the post-punk mavericks of early-80s Athens, Limbo District’s wild, perverse cabaret was “radical”, says Stipe. “They were intentionally abrasive, like Einstürzende Neubauten or Psychic TV, but they had melody, humour. They rewrote where punk could go next, drawing on vaudeville and Edith Sitwell. They unsettled people, in a playful way.” Strickland remembers the band as “a mesmerising tapestry of pure imagination, with a sexy, surreal, Fellini-esque quality”.

after newsletter promotion

Athens loved Limbo District, but touring revealed them to be an acquired taste. “We’d clear the room,” says Crow. They recorded material with future REM producer Mitch Easter, but no one would release it. Bilbão grew anxious over her limited skills and fled to New Orleans, heartbroken. She was replaced by Tim Lacy, who was replaced, in 1983, by Crow. Around this time, Jim Herbert, a professor at the university, made Carnival, in collaboration with photographer Marlys Lens Cox. The remarkably surreal, dreamlike short film imagines Limbo District as “a 1920s existential travelling circus” pausing for respite by a lake and engaging in some nude wrestling. Stipe attempted to get MTV to screen Carnival. “But there’s butts and dicks and breasts in that thing,” Crow says. “They were never gonna play that.”

The band was on borrowed time anyway. Woodall fell into heroin addiction and spent subsequent years homeless, struggling with alcoholism and mental health issues. Stevenson’s brother Gordon, of New York “no wave” band Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, was an early Aids casualty; his death in 1982 broke Davey’s heart. He and Ayers broke up in 1983, ending the band, and Stevenson moved to France, to study philosophy at the Sorbonne. Amet, who had been arrested for shoplifting groceries and was facing deportation, went with him.

“Dominique had been in love with Davey since day one,” says Bilbão.

“Davey was everything to her,” nods Crow. “They lived together in an apartment where you could see the Eiffel Tower from the balcony.” Stevenson died of Aids in the early 90s. Amet subsequently married, had a son, and died 20 or so years ago. “None of us know any more than that,” sighs Crow. “She’d always told me she wanted a kid. She didn’t make it out of her 40s.”

Ayers, meanwhile, moved into painting and photography. “His paintings were quite beautiful – figurative and symbolic,” says Strickland. “He did a beautiful painting of Ricky, from memory, after Ricky’s death. Jeremy was always so open. You felt like you were seen when you spoke to him; you were being listened to and heard.”

Before she fled Athens, Bilbão would visit Ayers: “If I felt mad and everything seemed wrong. I’d have a cup of tea in his garden and talk and we’d be happy. It was like an oasis of peace, his big garden of bamboo.” It was here that Ayers died of a seizure, on 24 October 2016. He was 68.

“It was so tragic, but poetic,” says Herbert. “He died in that garden that he loved so much.”

In the years following Limbo District’s split, the B-52s and REM enjoyed multi-platinum success and critical acclaim. But the avant garde experimentalists who’d proved such a key inspiration to both groups were “lost in time as an entity”, says Stipe. It took Henry Owings, unofficial historian of the Athens music scene, to rediscover their legacy, releasing three EPs of unheard studio material and live album Live Limbo on his Chunklet Industries label (with more to follow); he is now organising screenings of Carnival across the world.

For years, Crow had been Limbo District’s archivist. “I carried all the studio recordings, live tapes, flyers and posters from home to home, for decades,” he says. “We’d always wanted to release our music, but could never afford to. I was about to give up on it. Then Henry reached out. Henry cared. Our music’s on streaming now. I can drive my car and listen to Limbo District on the stereo.”

Stipe is “just happy there’s renewed interest in Limbo District, that a shred of their influence still exists”. For Bilbão, it’s the memories of the people who made Limbo District that matter most. “The music was just an accessory – the important thing was the people,” she says. “I think about Dominique, Davey and Jeremy all the time. They were incredible. I’ve always kept them in my heart.”

Live Limbo is available now via Chunklet Industries. Carnival will be screened in the UK later this month.

Source: theguardian.com