E

In the beginning of this year, Danny Brown went to a rehabilitation center. He explains, “My aunt passed away and my family needed money for her funeral. However, I didn’t have the funds and I didn’t know how to tell them. They were aware that I had the money, but I had already spent it all on drugs and alcohol. I felt like I had let them down.”

This was not even the rapper’s lowest moment. In 2020, living in his native Detroit, he was well aware that he could overdose on drugs contaminated with fentanyl – a powerful synthetic opioid – but he didn’t seem to care. “I got to the point where I was pretty much suicidal,” he says.

Unfortunately, this year has been expected to be a triumphant one for Brown, a renowned rapper in the US. He has a highly anticipated sixth solo album, Quaranta, being released this month and his collaboration album with Jpegmafia, Scaring the Hoes, which debuted in March, is predicted to make it onto many “best of” lists by the end of the year. However, in addition to his musical success, the 42-year-old has been dealing with the challenges of fame, artistic expression, and the chaos of substance abuse and reckless actions that have shaped his public persona for the past decade.

Daniel Dewan Sewell, known as Brown, is recounting this tale from his recently acquired residence in the outskirts of Austin, Texas, a considerable distance from the colder weather of his hometown, Detroit. Upon entering, I am greeted by a scene of idyllic domesticity: fragrant candles, an array of delicate orchids and anthuriums neatly displayed on slatted plant stands, a large L-shaped couch, and two chihuahuas named Ditto and Samson. As a delivery of barbecue brisket and sausage is brought to us, Brown generously gives most of his portion to Ditto.

In 2021, he relocated to this area to live with his significant other, whom he had previously maintained a long-distance relationship with. He also wanted to be in closer proximity to the studio where he produces his comedic call-in podcast, The Danny Brown Show. Another significant factor was his desire to leave Detroit.

Born to teenage parents, Brown spent his childhood playing video games with a tight-knit family. His dad, a house DJ, passed on an obsession with music, and his mum read him Dr Seuss books and got him hooked on rhyme. But as he grew up, and after his parents split up, his life became less sheltered.

He shared with Complex magazine in 2012 that he began dealing drugs due to peer pressure and the belief that it would provide material for his rap lyrics. However, he was arrested multiple times and served eight months in jail. This experience only fueled his determination to pursue a career as a rapper, creating music that reflected the chaotic and troubled life on the fringes of society. His style of nihilistic hedonism offered a contrast to the financial crisis and ongoing wars of the late 2000s, standing out from the flashy and extravagant rap scene.

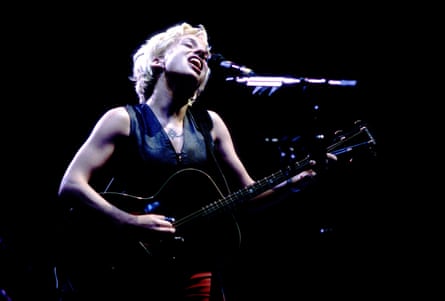

The name of his successful album, XXX from 2011, was inspired by the Xs imprinted on Xanax pills and his age, 30. Brown was aware of the irony of aging in a youth-dominated industry. His unique voice was easily recognizable: high-pitched, rough, and sharp like a popped blister.

The individual states that he overcame any negative factors that were preventing him from obtaining a record deal, including his age, slim body, missing teeth, and styled hair. Brown played a role in popularizing a new style of rap that was influenced by the use of prescription drugs and was embraced by the Awful Records group in Atlanta. This genre also attracted emo-rap artists like Lil Peep, who unfortunately passed away due to an accidental overdose in 2017. Additionally, mainstream artists such as Future and Lil Uzi Vert have incorporated elements of this style into their music.

In 2019, Brown reached the height of his artistic abilities with his fifth album, titled uknowhatimsayin¿. The album was executive-produced by Q-Tip, someone Brown greatly admires, which is uncommon in the music industry. Brown successfully straddled the line between being an unconventional innovator and a traditional hip-hop artist, a balance he had been struggling to maintain for nearly ten years.

Afterwards, in the following months, Brown turned 40 and experienced a breakup with his long-term partner, and his victory tour was canceled due to the pandemic. He was both financially and emotionally drained. “It was a difficult time, but the only way I could move on was to focus on making more music. I needed to get back in the studio because when things open back up, I want to be ready,” he reflects, realizing that he had been avoiding his problems. He relocated from the home he shared with his ex and their cats (she kept the cats) to a luxurious penthouse near his studio.

Creating music had turned into a way for him to justify indulging in excessive drinking. He gazes down at his lap while taking a drag from his vape and organizing his ideas. “I’m living in this amazing apartment with four bedrooms, but I feel so lonely. It got to the point where I was constantly getting high by myself every day.” He would consume a full bottle of alcohol daily, accompanied by a variety of drugs such as cocaine, pills, mushrooms, weed, or any other substances available.

In the music video for Ain’t It Funny, directed by Jonah Hill in 2017, Brown portrays a character from a sitcom who is addicted to crack and desperately seeking assistance while a pre-recorded audience laughs. Looking back, the video seems to foreshadow events to come. Brown reflects on his daily schedule during his stay at a penthouse in Detroit, where the cycle of binging and recovering blurred together, causing constant discomfort and frequent throwing up. He describes this time as hitting rock bottom.

Quaranta was created at rock bottom, serving as a detox and spiritual successor to XXX with its raw and vulnerable portrayal of life trapped in alcoholism. The title, meaning “40” in Italian, also alludes to the Covid quarantines and the painful isolation experienced by Brown as he spirals in his penthouse. The opening track, also titled “Quaranta”, sets the tone with honest lyrics and mournful spaghetti western guitar accompaniment. Brown’s voice is now calm and controlled, a far cry from his earlier years of high-pitched frenzy that he described as “having fun” in a 2013 interview with the Guardian. He explains that the album is his “low-voice” project, delving into the heavy themes of addiction and mortality. “So much fentanyl was going around at the time, so every bag of drugs was a risk,” he reveals. “I made this album with that in mind – thinking, ‘This might be my last album’.” In this way, the album alternates between Brown saying goodbye and giving himself a wake-up call.

Quaranta has been done for the best part of three years. For a while, Brown thought he was being shelved by his label, the experimental stable Warp, and sabotaged by his management. He said as much in drunken rants on his podcast and directed his fans to harass his manager and spam social media with the hashtag #FreeDannyBrown (this was another prompt to get himself to rehab). In the meantime, he hooked up with Jpegmafia and made Scaring the Hoes, an abrasive, claustrophobic tangle of blown-out drums, synths and chemical excess.

Brown stated that during the creation process, it was difficult to collaborate with him due to his excessive drinking. There were occasions where he would be too intoxicated to work and they would not make any progress for a weekend. However, there were also times where he would be productive and complete five songs in one day. Brown expressed interest in making another album together, but he would also respect the decision if his partner did not want to work with him again.

During their summer tour, Brown was sober and chose to travel in a separate car behind the tour bus for his own well-being, rather than any personal issues. Ordinary experiences, like hearing fans sing along with his lyrics, affected him in a different way. He shares, “I actually started to enjoy being on stage again.” Performing sober became therapeutic for him, as he could see the joy and happiness in the audience. This positive energy had a direct impact on him, almost like a daily “fix.” In his day-to-day life, he receives similar feedback, such as when he proudly shows his phone app that tracks his 200+ days of sobriety. He is determined to continue this streak.

He is not dwelling on his artistic limitations, either. According to him, creating music is comparable to a challenging level in a video game. In the past, he would stay up all night attempting to conquer it. But now, he understands that he can simply step away, go to sleep, and most likely succeed on his first try the following morning.

Brown remains cautious about Quaranta being a pivotal moment for him, as he has concerns about how his recent shift towards a calmer demeanor could impact his artistic output. He shares, “I’ve witnessed many artists who became sober and then their music suffered.” However, being sober has also given him a newfound sense of patience and perspective. He explains, “I believe that with the release of this album and reflecting on the struggles and challenges I faced while making it, it’s like having a happy ending at the end of a movie. It’s amazing to see where I am in my life now.”

On November 17th, Warp Records will release Quaranta.

Source: theguardian.com