I

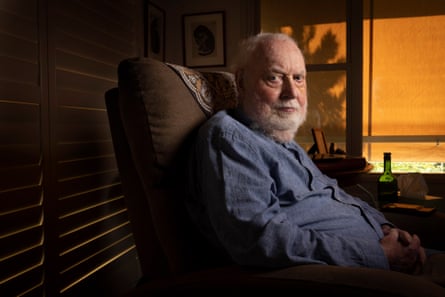

In late November, the esteemed film critic David Stratton is presenting his final lecture on global cinema at the Center for Continuing Education at the University of Sydney. After 35 years of dedication to his students, some of whom have reciprocated by enrolling for 32 years in a row, Stratton is not physically present tonight.

Although he continued to make trips from the Blue Mountains to the city during the Covid pandemic, his eyesight had been declining and he had recently suffered a spinal fracture. However, a sudden month-long hospital stay greatly disrupted his plans. With only four weeks left in the course, he reached out to the director Claude Gonzalez for assistance.

On this final evening, Stratton calls in to bid students goodbye and share his all-time beloved film, Singin’ in the Rain: “I was raised on musicals and this is the greatest one ever created.”

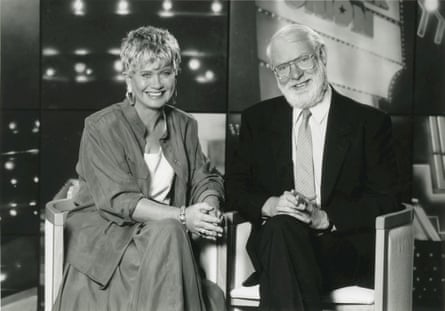

Stratton, known for his 28-year tenure co-hosting The Movie Show (SBS) and At The Movies (ABC) with Margaret Pomeranz, has a distinct speaking style that is well-known to most Australians. He speaks plainly and confidently, even standing his ground when Pomeranz disagrees. Regardless of his opinion of a film, his tone always reflects his passion for cinema.

The feeling of tenderness is quite apparent this evening. The 84-year-old remarks to the group about the scene where Gene Kelly dances in the rain with an umbrella, as the camera captures the moment with a soaring crane shot and the music reaches a climax. This moment is a perfect example of pure cinema and is unmatched in my opinion.

The students in the auditorium are feeling devastated and immensely saddened as the course comes to an end. Stratton addresses the audio-visual technician, Michael McCartney, and asks him to play the MGM lion’s roar.

W

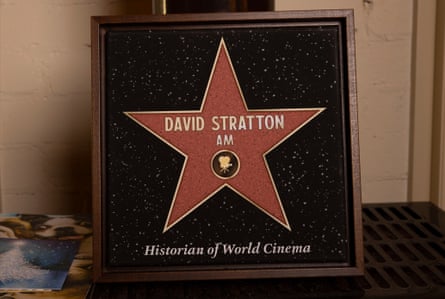

When David Stratton’s last review is published in The Australian today, it marks the end of his 57-year career as a staple in Australian media, including television, newspapers, radio, and literature. Gonzalez reflects on how Stratton has been a fixture in their film discussions and presence in their homes. His passion for cinema is unmatched.

Regarding retirement, Stratton states that one cannot continue indefinitely. He feels at ease with this decision and is satisfied with the work he has done over the years. He has informed film-makers and distributors that he will no longer be reviewing, and has received positive messages in response.

Stratton’s Thursday evening course, a history of world cinema, ran over two 12-week semesters a year. When it began in its current format in 1990, Stratton could move from the origins of cinema to around 1980 at a fairly fast clip. As the years passed, he says, more films became available “so the progress of the course slowed dramatically”.

The course expanded to include Nazi cinema, Russian cinema, and other topics, filling in the gaps. This allowed devoted student Michele Aspery, who enrolled every year since 1990, to never watch the same feature film twice thanks to their meticulous teacher. Aspery approximates that Stratton has shown around 840 films and 7,506 clips.

She claims that he is the top educator in Australia, and potentially even the world, due to his extensive understanding of cinema and ability to obtain films.

Graham Heath has been attending for the same amount of time as well. He stated, “I made a promise to myself that as long as David continued to come, I would too.” Unfortunately, now that David is no longer able to attend, that signifies the end for me as well.

Flynn Boffo, a student studying screen production at the age of 22, recently joined the program this semester. During a screening of the 1957 western film The Tall T, Boffo experienced one of his teacher’s main annoyances. “A few of us chuckled in response to the misogyny and David was not pleased,” Boffo explains.

Stratton remembers, “There were some newcomers to my course who broke the rule, and I feel strongly that movies reflect their time.” He shares a quote from LP Hartley’s novel The Go-Between, “The past is like a different country, with its own customs. If you visit a country with different customs, you shouldn’t make fun of them.” He can’t forget the time he watched a silent film and the audience laughed the whole time. “I was appalled by that. It’s disrespectful to mock something that was once considered valid.”

In 1966, Stratton gained recognition for his work in fighting against film censorship. This resulted in an opportunity to lead the Sydney film festival, which he did for a period of 18 years. During this time, he expanded the festival’s reach and influence.

During my time as director, the Australian film industry experienced a renaissance. This allowed me to showcase the debut works of talented filmmakers such as Peter Weir, Gillian Armstrong, Fred Schepisi, and Phillip Noyce. I was able to develop friendships with these individuals during this period. Not only was it a thriving time for the film industry in Australia, but it was also a remarkable era for cinema on a global scale in the 1970s.

When discussing his professional life, the words “invited” and “asked” come up frequently. Stratton expresses surprise when stating, “I never applied for a job,” possibly because he did not receive a university education. He also notes, “I never finished high school.” Despite being self-taught, Stratton has authored five books and received two honorary doctorates. He has served on numerous international film festival juries, led by notable individuals such as David Lynch and Annette Bening. He is also known for his entertaining storytelling abilities. On one occasion, he called in for his regular Friday show on 2UE from director Noyce’s Los Angeles home. Despite seeking a quiet room, he was interrupted by Uma Thurman and Nicole Kidman, who tried to make him laugh on air by making funny faces.

In the 1980s, Stratton’s list of responsibilities began to increase. He journeyed to various countries, participating in prestigious film festivals. In 1984, he also started critiquing for Variety, a publication read by the elite in the entertainment industry. Was he concerned that his voice was too dominant? “I did have concerns,” he admits. “It’s important to have diverse opinions.” However, people were persistent in offering him jobs. “I may have taken on too much,” he reflects. But ultimately, with his characteristic decisiveness, he says, “Regardless, I did it.”

T

Stories of living a luxurious lifestyle, including travel, fine dining, indulging in wine, and spending time with friends in the film industry, are intertwined with Stratton’s strong dedication to work. He disagrees with former film critic Paul Byrne’s belief that one cannot be friends with filmmakers. Stratton explains that while he has been on good terms with many filmmakers, it can be challenging as not all of their films are of high quality. If Stratton had to give a negative review of a friend’s film, he would give them a courtesy call beforehand. However, he would still fulfill his role as a critic.

From 1980 to 2003, Stratton served as the feature film programmer at SBS. During his tenure, he introduced numerous foreign films to the local community, often providing English subtitles for the first time. He takes pride in knowing that people continue to discover new films and directors through SBS, even to this day.

He met Margaret Pomeranz at this place, where she worked as a producer for SBS. They became friends after having several alcoholic lunches and realized that Australia did not have a TV show specifically for reviewing movies. Initially, they looked for another co-host from outside. However, Stratton strongly believed that having a female co-host would improve the show. Despite their efforts, they were unable to find someone and Margaret ended up stepping in at the last minute, proving to be an excellent addition.

The pilot for their show was deemed “terrible,” so they kept it a secret from SBS executives and immediately started filming episode one. According to Stratton, no one had actually seen the pilot before it aired. They hosted a viewing party at Margaret’s house, inviting a few filmmakers, and to their surprise, the show was a hit from the beginning and quickly gained a following.

Margaret and I had differing tastes when it came to movies. While I would eagerly watch any and all films, Margaret was more particular and didn’t frequent the movie theater like I did. She was more like the majority of people who are selective about what they choose to watch.

Is it possible that their well-known conflicts were planned? “Prior to our meeting, we were unaware of each other’s thoughts. Everything was completely unscripted.”

For every Stratton story about a famous actor or director, his students have stories about their teacher’s dedication – calling them with answers to questions he didn’t adequately cover in class, or providing printed lists of obscure French films.

“I have accumulated a great deal of knowledge about cinema from various countries that produce films. My goal was to share this knowledge with others,” he explains. “The fact that people were interested in hearing and seeing it was an added bonus. Even if nobody had been present, I still would have done it.”

Stratton envisions his retirement as a time for unwinding, reading, and resting. He desires to watch a different movie each day, preferably one he has not seen before. Occasionally, he would also like to revisit a classic film that he enjoys. This is his ideal retirement plan.

Movies in Stratton’s final term of a course on the history of global film.

Brief Encounter (1945); Charlie’s Country (2013); Blackmail (1929); The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961); Alias Betty (2001); One, Two, Three (1961); Talk To Her (2002); Witness (1985); The Tall T (1957); Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988); Duck Soup (1933); Singin’ in the Rain (1952).

Source: theguardian.com