A scornful wife wrote a letter to her husband, who had apparently left her behind when he traveled to the Americas. The letter, which had been left unopened for almost 300 years, is part of a collection of 18th-century Spanish ship documents seized by the British and now accessible online.

On 22 January 1747, Francisca Muñoz from Seville sent a letter to her husband, Miguel Atocha, who was in Mexico at the time. This letter was one of 100 similar letters written by Spanish women to their husbands, discussing the difficulties they faced emotionally and financially while their partners were away. The letters were discovered on the ship La Ninfa, which was registered and traded between Cádiz and Veracruz, Mexico. However, the ship was captured by the infamous British privateer squadron known as the “Royal Family”.

My loving husband, I am overjoyed that this letter has made its way to you and that you are in good health. I am curious as to why I have not received a response to the 13 letters I sent. Is it possible that you do not have access to paper, pen, or ink to write back to me?

She expresses her unhappiness, feeling like she has more misfortunes than anyone else in the world. She also feels burdened by physical and emotional suffering, and on top of that, she has to care for your two children who you seem to love more than her.

Miguel, their son, has grown into a man with a bigger physique than yours and is currently unclothed due to the lack of work or opportunities to earn any income in this area.

She and her daughter, Maria, have been compelled to serve as household workers, despite their ailments. Her own health issues include a throat abscess, preventing her from even asking for money to see a surgeon due to being weak and hungry. She shares, “There are days when I go without water because I have nowhere to get it from, and I am too sick to go door-to-door begging.”

Their son requires a cloak from someone in order to attend mass. Their daughter was forced to marry the son of Estacio Hidalgo, also known as “the beach man”, without her father’s consent. Her unfortunate story goes on to share that Maria had a child who was admired by all of Triana and Seville, but sadly passed away after only 14 months.

She writes: “Your wife, Francisca Muñoz, who wants to see you.”

The documents and objects from approximately 130 Spanish ships that were taken by the British during the conflicts of Jenkins’ Ear (1739-1748) and the Austrian succession (1740-1748) are now accessible online through the Prize Papers project.

José Pascual Marco, the Spanish ambassador to the UK, said the papers were invaluable “to understand the world, in its fine grain, in its flesh and blood, in its complexity – and that is what we have in these papers”. They provided, he said, “the human story of the Americas”.

From 1652 to 1815, British privateers and navy ships took control of approximately 35,000 boats. They confiscated hundreds of thousands of documents, including 160,000 undelivered letters in 20 different languages that are still preserved as the Prize Papers. These papers are currently being converted into a digital format through a collaborative effort between the National Archives in the UK and the University of Oldenburg in Germany, with a projected timeline of 20 years.

Bypass the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

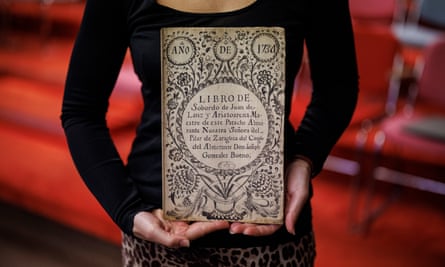

The recently published Spanish documents consist of two exquisitely illustrated books from the Nuestra Señora de Covadonga, a valuable ship taken over during its voyage from Acapulco to Manila in 1743. The ship’s cargo included a significant amount of silver in the form of reals and pesos. Another document is a message sent to the governor of the Philippines in 1742 from King Philip V, directing him to provide shelter to Danish ships.

At the same time, a 16-year-old boy named Joaquín Ruiz de España, who moved with his father from Sanlúcar de Barrameda to Veracruz in Mexico, sends a letter to his friends recounting a near-death experience on their ship as it was getting ready to leave Havana.

While ascending the ship’s ladder at 10 PM, I lost my footing and grip in the dark of the night and tumbled into the water. Thankfully, I was able to stay above water more through divine intervention than my own abilities.

The father of the non-swimming son tossed a rope to him. The son expressed that he felt it was by the will of God, the Holy Virgin, Saint Joseph, and Saint Anthony that he was able to hold on, as he was struggling to breathe and on the verge of passing out.

He went on to say, “I imagined myself facing death and believed that because I was such a sinner, God would surely end my life.”

Source: theguardian.com