L

The Michael Werner Gallery, located on a street adjacent to London’s Park Lane, exudes an air of affluent sophistication in the art world. Hidden in a discreet Georgian townhouse, it is easy for a passerby to overlook its presence. It is not unexpected to discover the paintings of the late Don Van Vliet in this prestigious setting, as Michael Werner has been his gallerist since the 1980s, when Van Vliet retired his stage name “Captain Beefheart” and shifted his focus to visual art. However, despite this connection, the paintings showcased in his first London exhibition in decades seem somewhat out of place in their surroundings.

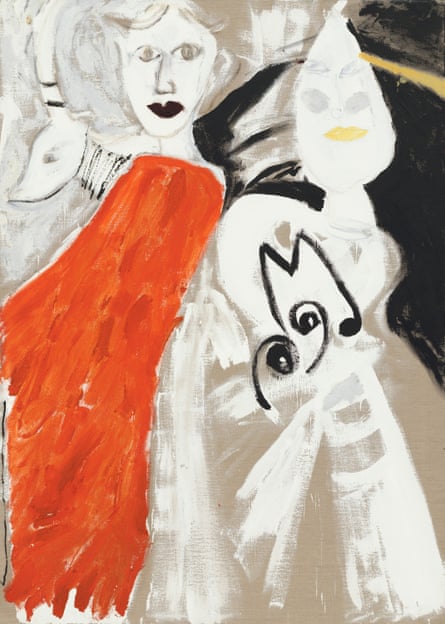

One reason for this is that they clearly reflect the influence of California’s wilderness, where Van Vliet resided and worked in the Mojave desert for a period of time. His paintings depict various wild animals and cacti, but as his career progressed, the natural elements started to dominate the canvas, leaving more white space as if bleached by the intense sunlight. The paintings also give off a sense of frenzied and untrained energy with bold brushstrokes and thick layers of paint applied directly from the tube. However, the most significant factor is that regardless of any name changes, these works are unmistakably the creations of Captain Beefheart, a highly acclaimed figure in the music scene of the 1960s and 1970s.

The titles often reflect his previous songs or lyrics: those familiar with the tracklisting of his 1969 masterpiece Trout Mask Replica will recognize the title China Pig, while Crow Dance a Panther and The Drazy Hoops are inspired by lines in Ice Cream for Crow and The Blimp respectively. Even if they do not directly relate, they have a similar feel: Dream Sloth, Full Grown Babble, Bird With Cotton Shadow. And, similar to his music – which drew from blues and free jazz, but had a unique sound unlike anything else in pop history – these titles have proven difficult to categorize.

After perusing articles showcasing his art journal, one is struck by the critics’ tendency to compare his works to various artists, hoping that one comparison will stick. These comparisons include names such as Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and movements like expressionism, primitivism, and outsider art. However, Gordon VeneKlasen, managing partner of the Michael Werner Gallery, argues that this work cannot be considered outsider art as it implies naivety and lack of awareness of art history, which was not the case for the artist. VeneKlasen personally had lengthy conversations with the artist, during which he observed his precision and careful choice of words and thoughts, which he believes translates into his paintings as well.

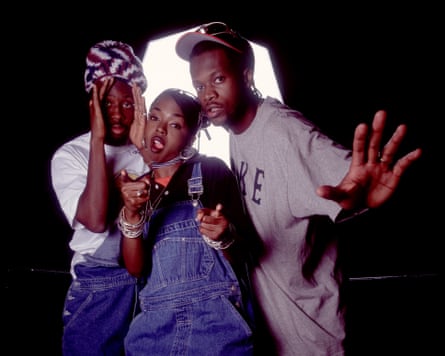

The story of how Don Van Vliet, also known as Captain Beefheart, transitioned from avant garde rock legend to visual artist actually began before he adopted his famous stage name and created the original Magic Band. As a child, he showed exceptional talent in sculpting, winning awards and even appearing on television to demonstrate his skills in creating animal sculptures. According to Van Vliet’s own account (although he was not always a reliable narrator of his own life), he was offered a scholarship to study art in Europe at just 13 years old. However, his parents refused to allow him to pursue this opportunity, citing their belief that art was “strange”.

Throughout his career in music, he continued to paint. His artwork was featured on album covers and was showcased in a 1972 exhibition in Liverpool. However, it was often overshadowed by his music. With the release of Trout Mask Replica, Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band’s sound was incredibly unique. Even 54 years later, it remains one of the most challenging albums to listen to, often appearing on lists of the greatest albums of all time. Each instrument seems to play in its own universe, with little connection to the others. Some consider it barely qualifying as music, while others see it as a groundbreaking work of genius. John Peel even suggested that it could be considered a work of art in the history of popular music. John Lydon called it a “confirmation” for him, opening up possibilities for different styles and sounds in music.

AR Penck, an artist from East Germany, was one of its admirers and was managed by Michael Werner. According to VeneKlasen, when Penck fled to the western side in 1980, he continuously urged, “You must discover Don Van Vliet, he is the artist you must discover. Don was his ultimate inspiration.”

Penck’s proposal posed an issue, despite Werner’s admiration for Van Vliet’s artwork and his suggestion for representation. According to VeneKlasen, it is now common for individuals to have multiple careers, but in the 1980s, being both a musician and a painter was not taken seriously and was even seen as a joke. The creation of art held a certain weight and the creation of music was viewed as something completely separate.

It is not clear who first proposed the idea for Van Vliet to quit music entirely, abandon his stage name Captain Beefheart, and focus on painting instead. Some sources say it was suggested by Werner and Penck, others claim it was his wife Janet, and another maintains it was entirely Van Vliet’s own decision. This was likely motivated by the lack of interest from record labels in funding a new album after the disappointing sales of his 1982 release, Ice Cream for Crow. However, if it was someone else’s suggestion, he did not need much convincing. According to reports, he was exhausted and disheartened by his music career, having already cancelled a planned tour and being forced to live in a trailer owned by his mother due to financial struggles. VeneKlasen remarks, “He had been mistreated by the music industry, so he ultimately decided to give it up completely and pursue painting instead.” He was not bitter, but he held resentment towards the music business.

It is possible that there were other reasons behind his choice to leave the music industry. Van Vliet’s interactions with his bandmates were frequently tense. Some former members of the Magic Band have labeled him as “oppressive,” and Zoot Horn Rollo’s book, Lunar Notes, portrays their time together as constant suffering: financially struggling, barely surviving on a daily diet of soya beans, and enduring mental and emotional abuse from their leader, which sometimes escalated to physical altercations.

Ignore the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

A possible explanation is that Van Vliet possessed a unique artistic perspective, which involved creating incredibly intricate and demanding music, and he was determined to achieve this at any cost. However, VeneKlasen notes that it is easier to pursue a singular artistic vision when you are the only one pursuing it. “I believe he was quite controlling, but the music did involve other individuals. However, as he aged, he grew to dislike people. I remember visiting him in Eureka, California – he lived in a secluded area. I think painting was more thrilling for him because it was a solo endeavor.”

However, despite Van Vliet’s dedication to his new career path, there were challenges. Persuading him to leave California was difficult, as VeneKlasen attempted in vain to convince him to move to New York. Van Vliet responded by stating that there was too much “human skin in the air” in the city and famously referred to it as “a bowl of underpants.” While his early shows attracted Beefheart fans, the art establishment was not receptive. According to VeneKlasen, they viewed him as a “holy figure” due to his association with Van Vliet. It wasn’t until 1986, when museum director Jack Lane organized a show of Van Vliet’s work at the San Francisco MoMA, that there was some recognition for him in the art world. However, even then, Lane faced backlash and almost lost his job. Many dismissed Van Vliet as a musician who dabbled in art rather than a true artist. It wasn’t until after his death in the last decade that there has been a shift in perception, largely influenced by other artists rather than curators. In fact, many painters, including German abstract painter Charline von Heyl, have expressed their admiration for Van Vliet’s work. However, if one were to approach a curator at a prestigious institution like the Tate, they would likely dismiss Van Vliet’s work, while other respected artists would be surprised by this reaction.

Until his passing in 2010, Van Vliet persisted in his work despite the challenges of multiple sclerosis. As his health declined, the gallery created a device for him to paint while seated, but he eventually turned to drawing. He never returned to his music. According to VeneKlasen, “He was fiercely uncompromising and did things on his own terms. He was a true reflection of the chaotic environment of California during that time, with bombings and construction projects happening. I remember him telling me that he even worked as a vacuum cleaner salesman and sold one to Aldous Huxley!”

He chuckles, but then hesitates due to Van Vliet’s tendency to exaggerate and often have a strained connection with reality. “I didn’t verify it. I should probably check and see where Aldous Huxley resided during that time. But as a narrative about California during that era, I found it to be compelling. It’s reminiscent of Brave New World, and it’s just bizarre. California was certainly an odd place.”

Source: theguardian.com