D

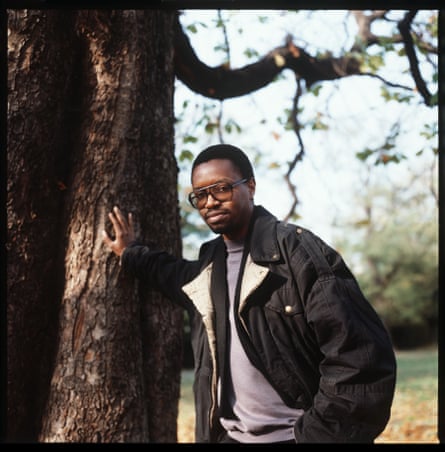

Throughout the 1980s, Wally Badarou, a groundbreaking French keyboardist and synthesizer pioneer, contributed his talents to numerous hit singles and albums for a diverse range of artists such as Grace Jones, Talking Heads, Robert Palmer, Level 42, Mick Jagger, Herbie Hancock, Jimmy Cliff, Gwen Guthrie, and Julio Iglesias. Despite his proximity to these renowned musicians, Badarou claims that there was only one instance in his illustrious career where he knew a song was destined to become a hit: Foreigner’s “I Want to Know What Love Is.”

“It was intended to be that way,” he states about the classic soft rock power ballad. “Both the record company and I wanted it that way. As for the other songs, like Pop Muzik, Addicted to Love – those weren’t originally planned to be hits – Burning Down the House… I was surprised when they became hits. It was quite interesting.”

The mix of styles in Badarou’s music can be attributed to his upbringing in Paris, where he began his career as a studio musician in the late 70s. During this time, he collaborated with artists such as Manu Dibango and the Gibson Brothers, and developed a strong relationship with their producer, Daniel Vangarde (father of Daft Punk’s Thomas Bangalter). Badarou reflects on this period as a valuable learning experience, recalling the pressure to deliver quality work within tight timelines due to the high cost of studio time. This experience gave him the confidence to work with artists like Foreigner and adapt to different musical styles.

His musical dexterity was also born of circumstance. His parents, who listened to classical music, moved the family to Benin (then Dahomey) when Badarou was seven. By the time he returned to Paris in 1971, aged 16, he “had synthesised those two cultures – African and European – before I even got into synthesisers.”

Becoming proficient in early synthesizers, which required manual programming and live performance, made him highly sought after. During one session, which was nothing out of the ordinary except that it was for a pornographic film – a one-time occurrence, he admits sheepishly – he collaborated with British musicians for the first time. This led to a jam session with a jazz-fusion style that caught the attention of bass player Julian Scott. He then introduced Badarou to a project his brother Robin was involved in. A few days later, Robin contacted Badarou and invited him to join them in a small studio in Paris. It was at this studio that Badarou worked on the hit song “Pop Muzik.”

He gained fame and recognition after being featured on M’s groundbreaking pop album. While collaborating with Talking Heads on Speaking in Tongues, David Byrne inquired about the song that foreshadowed the electronic sound of the 1980s. Byrne was curious about the innovative production techniques used and saw the song as a pioneering statement in music. The artist responded humbly, saying “Maybe!”

Chris Blackwell, the owner of Island Records, was also a fan of the track. He was searching for a European synthesizer player to join a group he was assembling at his Compass Point Studio in the Bahamas to help Grace Jones with her artistic revival after her disco album trilogy. He asked Vangarde if he could recommend anyone, and Vangarde suggested Badarou. Chris recognized Badarou as the same person who worked on “Pop Muzik,” and knew he was the perfect fit for his project.

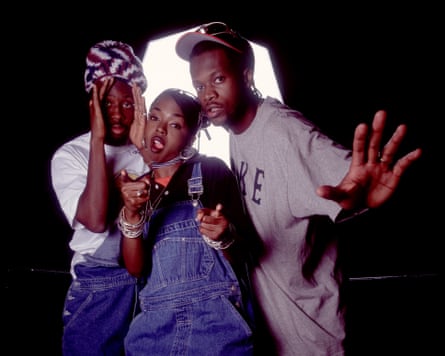

Badarou explains that it was a mere bet that led to the formation of the Compass Point All Stars, a diverse group of musicians from various countries. The group, referred to by Jones as the “United Nations in the studio”, consisted of renowned Jamaican musicians Sly Dunbar, Robbie Shakespeare, Mikey Chung, and Sticky Thompson, as well as British guitarist Barry Reynolds who had recently worked on Marianne Faithfull’s album Broken English.

Initially, Badarou was not impressed. The sessions did not begin punctually, his lodging was dissatisfactory, and he was not accustomed to waiting around. He completed his work for Jones’s Warm Leatherette and Nightclubbing albums in three weeks; the remaining three weeks were spent idling around. He couldn’t return to France soon enough.

After returning to Paris, he was able to listen to a preliminary version of the new wave dub disco track “Private Life” by Jones. This experience completely changed his mood, as he had never heard music like this before. He was filled with pride at the incredible creation they had made. He soon went back to Compass Point, where he developed a strong connection with the studio and even built his own in his bedroom. This marked the beginning of a 14-year love affair with the studio and a lasting friendship with Blackwell. Whenever they worked with Sly & Robbie, Blackwell’s enthusiastic body language served as a sign that they were creating something truly special. The energy in the studio was indescribable and no words were needed to convey the excitement.

During a flight, Blackwell quietly said to Wally, “I truly believe that our band is the best in the world with you guys.” Badarou recalls that he was sincere and earnest in his statement.

Blackwell is the catalyst for his current state of speech. In 2000, Blackwell’s significant other Nathalie Delon (previously wedded to actor Alain Delon) recorded a yoga DVD. After forming a close bond 20 years prior as the sole French individuals at Compass Point, Delon inquired if Badarou had any music to contribute. He shared some demos he had been working on, not anticipating that there would be any suitable for yoga. Delon was enamored with the ethereal Afrofuturist melodies and upon the release of the DVD, a restricted CD of the music was made available.

Throughout the years, Colors of Silence has gained a revered status among fans of experimental Balearic music. According to Badarou, who worked on the album, the music was intentionally sparse and evoked a sense of silence. This month marks the first release of the album on vinyl. The demos from this project also serve as the foundation for The Unnamed Trilogy, an album that Badarou has been developing for three decades.

“I possess a vast amount of music,” he states regarding this unreleased trilogy. “However, I have chosen to keep that special quality to myself. Magic is the term. It is not about being flawless. I am not striving to be the greatest. My desire is for it to be magical. Those demos held a certain magic and even after 10, 20, or 30 years, they still hold that magic to my ears.”

Although he prefers not to share juicy stories about his time at Compass Point, Badarou does recall that Grace Jones was not his favorite person to work with. Some notable musicians who visited his bedroom studio included Mick Jagger and Jeff Beck, who collaborated on Jagger’s solo album She’s the Boss in 1985. Badarou was surprised by Jagger’s dedication to perfecting his vocals, spending weeks on the recording. On another occasion, Paul McCartney, Robert Palmer, and Kraftwerk collaborator Emil Schult stopped by while McCartney was on vacation nearby. Badarou regrets not having the technology to take selfies at the time. While Emil did keep a recording of their jam session, it didn’t produce anything remarkable, as far as Badarou can remember.

On another occasion, Badarou traveled from Paris to Nassau and the trip lasted 20 hours. When he arrived, he was approached by engineer Godwin Logie to add some synth lines to Gregory Isaacs’ new album. The first song they worked on was “Night Nurse”, but Logie asked for more and Badarou ended up recording the entire album in one take per song. At the time, Badarou didn’t realize how successful Gregory Isaacs would become and he just wanted to rest. However, he does regret a session he had with James Brown, as his manager, Reverend Al Sharpton, claimed all the music they worked on would be credited solely to Brown.

Badarou’s music has stood the test of time. One notable example is his song “Mambo,” which he recorded for his highly acclaimed 1984 solo album “Echoes.” This track later became the foundation for Massive Attack’s hit song “Daydreaming.” However, Badarou’s proudest moment came in 1992 when France held a referendum on the Maastricht Treaty, a crucial component of the modern European Union. One evening while watching the news, Badarou was surprised to hear his song “The Dachstein Angels” from his 1989 solo album “Words of a Mountain” playing in the background of a pro-Treaty rally. He remarked, “They didn’t ask for permission, but it was amazing.”

Shortly thereafter, another individual began utilizing the music – the head of the extreme-right National Front party, Jean-Marie Le Pen. “I suppose they were unaware of the composer’s identity.” Once they discovered Badarou’s name, they ceased using his music. “I felt a sense of pride that day because I had made my stance clear,” he states. “It’s not about where you originate from; it’s about your growth and development. That’s what truly matters. I have blended all of these cultures because I am both European and African.”

Source: theguardian.com