‘T

I have three tips that I always share with my students: firstly, make sure to arrive on time. Remember, time is valuable so don’t let it go to waste. Secondly, don’t let your ego get in the way. Stay focused and perform your best. And lastly, stay attentive and listen closely. If you can put your ego aside and listen carefully, you’ll be able to understand the music and make a meaningful contribution.

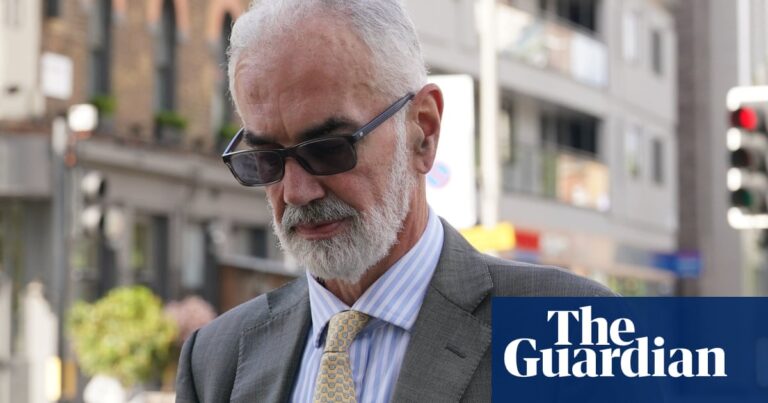

According to Ron Carter, at 86 years old, he is still a prominent figure in American music. With a record of playing on over 2,250 albums, he holds the title of the most recorded bassist in jazz history in the Guinness World Records. Carter, who is also a professor at several universities in New York, states that he loves making music and considers himself a servant to it. While he enjoys being a bandleader and making decisions, he also appreciates the opportunity to play with other musicians and contribute to their vision. He sees it as a learning experience and a beautiful process. And as an added bonus, he jokes that playing sessions also pays well.

Carter’s Foursight quartet will be holding two concerts at the London jazz festival during this month. As a bridge between bebop and hip-hop, the sophisticated double bass player is considered a pioneer in the UK’s flourishing jazz community.

Carter’s exceptional skill, strong and energetic swing, and rich and powerful sound have established his bass as a unique instrument, much like Miles Davis’s trumpet or Thelonious Monk’s piano. This sound has connected him with an impressive list of jazz legends – Bill Evans, Chet Baker, Sarah Vaughan, Stan Getz, Lee Morgan, Lena Horne, Cannonball Adderley, Helen Merrill, Charles Lloyd, Sonny Rollins, and Freddie Hubbard – as well as iconic figures in pop, rock, and soul such as Paul Simon, Billy Joel, Aretha Franklin, Roberta Flack, Santana, Gil Scott-Heron, and Erykah Badu. When rapper Q-Tip asked Carter to play on A Tribe Called Quest’s album The Low End Theory in 1991, his smooth bass helped usher in a brief fusion of jazz and rap.

Interestingly, Carter did not originally intend to pursue a career in jazz. He grew up in Detroit as a classically trained musician, with the cello as his main instrument. However, due to segregation, Carter was unable to fully realize his potential in this field. He recalls how, as a young musician, he was often overlooked for performances at school events in favor of white students. In response, he made a practical decision to switch to the double bass, as the school’s current bassist was set to graduate soon and there would be a need for a replacement. Carter sold his cello and used the money to take bass lessons, ultimately joining the school orchestra in January of 1955.

As skilled at bass as he was cello, Carter enrolled in a music degree at the University of Rochester yet, once again, was limited by institutional racism. “I realised that the people who did the hiring for philharmonic orchestras weren’t interested in employing African American musicians. It was obvious.” The same pragmatism that saw Carter adopt bass over cello meant he turned from classical to jazz. “As a student I had a weekend gig in the house band at a Rochester club where we backed visiting jazz musicians. I didn’t initially give it serious thought but I was encouraged by several people who came through there – Sonny Stitt, among others – to come to New York when I graduated.” Carter notes that he wasn’t the only Black classical musician exiled to jazz. “Hubert Laws was another. And Miles studied at Juilliard for a year before determining there was nothing they could teach him. There’s a few of us.” I mention the old cliche that jazz is America’s classical music. “That’s exactly right!”

In 1959, Carter made a permanent home in New York and became a member of the drummer Chico Hamilton’s quintet. He formed a dynamic collaboration with the band’s innovative saxophonist-flautist, Eric Dolphy. Carter fondly remembers his friend, who passed away unexpectedly in 1964 due to diabetes, as a talented musician and a kind person. He admired Eric’s impressive skills and innovative ideas, particularly his unique approach to harmonics, and thoroughly enjoyed performing alongside him.

In April of 1963, Carter received consistent work and was participating in a two-week stay with Art Farmer at Half Note club in New York. During this time, Miles Davis arrived and lingered near the jukebox.

During intermission, Miles approached me and informed me that Paul Chambers was leaving his band to join Wynton Kelly’s and asked if I would be interested in joining him for an upcoming tour. I responded by saying “Mr. Davis” (I didn’t call him Miles yet), “I am contractually obligated to work with Art for the next two weeks. If he gives me permission to leave early, then I would be happy to join you. Otherwise, I must honor my commitment.” Miles exclaimed “What?” and then went to speak to Art. Art gave me the go-ahead to leave, so I joined Miles on tour. This showed Miles that I was reliable and willing to keep my word, and it set a good foundation for our relationship.

With 25-year-old Carter on board alongside the drummer Tony Williams (17), the pianist Herbie Hancock (22) and the saxophonist Wayne Shorter (33), Davis launched his second great quintet. Across the next five years they would redefine modern jazz, releasing six albums that blended the modal explorations of Davis’s 1950s quintet with electric instruments and increasing experimentation. Here, Carter’s fluid playing and original compositions established him at the forefront of the US scene.

Carter explains that the band functioned like a laboratory with Miles as the leading chemist. He takes pride in the music they created and believes it still holds strong even today. In the studio, Miles didn’t give orders but instead focused on what each member could contribute to the session. It required active listening, attentiveness, and comprehension to see the project come to fruition. It was an exciting journey.

“I gained valuable experience from collaborating with Miles. One important lesson I learned was that being a band leader requires strong fortitude as all the responsibilities fall on your shoulders. I decided to leave Miles in 1968 due to extensive traveling and a desire to spend more time at home. However, by this point, I had established myself as a sought-after session musician and knew that I could still thrive without constantly being on tour.”

Bypass the advertisement for the newsletter.

after newsletter promotion

In 1969, Carter had a significant year: his sophomore album, Uptown Conversation, received widespread acclaim and he was involved in various recording sessions, such as playing on Aretha Franklin’s Soul ’69 album and Roberta Flack’s First Take. The latter, which was Flack’s debut, featured the song “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” which became a US No. 1 hit in 1972 after it was included in the love scene of Clint Eastwood’s film Play Misty for Me. Carter’s bass playing provides a solid foundation for the song, adding a sensual quality with its deep tones.

According to Carter, Roberta Flack is an exceptional vocalist and talented pianist. Working with her was a dream come true for him. In the studio, Flack would play the songs while Carter would listen and add his own touches to enhance each piece. He would add notes where he felt they fit best. While Aretha Franklin was known as the queen of soul singers, she was also a gifted pianist. In the studio, she would question Carter’s musical choices and he would jokingly reply that he was following divine guidance. Their working relationship was highly enjoyable.

James Brown was a renowned musician who was supported by Carter. According to Carter, R&B musicians strive to replicate the sound of their recordings while jazz musicians do the opposite. In addition to his dedication to playing for others, Carter has released numerous albums as the leader of his own band. These albums range from smooth jazz fusion to memorable collaborations with talented peers, as well as solo bass performances. He even has a series where he plays Bach on the double bass. Along with his musical pursuits, Carter has also written multiple books on bass instruction and teaches classes and offers private lessons. The only things that have slowed down this jazz genius are the pandemic and a back injury, which caused him to cancel his 2022 shows.

When I inquired about his motivation, Carter recalls, “The best advice Miles ever gave me was at the beginning of our professional partnership. He told me to ‘play the music well’, which meant not making excuses or becoming lazy or bored. Even if you’re sick, give your best performance. I have always strived to follow that advice and share it with my students: to play the music well.”

Source: theguardian.com