In one of the Rolling Stones’ most crucial songs, Sympathy for the Devil, it’s not Keith Richards’ guitar that defines the melody or propels the piece. It’s a series of stark piano chords, struck by a studio musician, that give the piece its earth-shaking power. Likewise, in the Who’s classic cut The Song is Over, it isn’t Pete Townshend’s six-string that provides the song’s most plaintive tug. It’s a piano progression, provided by a guest player, that lends it that melancholy grace. Similarly, in Joe Cocker’s smash hit You Are So Beautiful, Cocker finds his dream partner in a series of guest piano runs so elaborate they change the trajectory of the melody, ultimately soaring it to the sky.

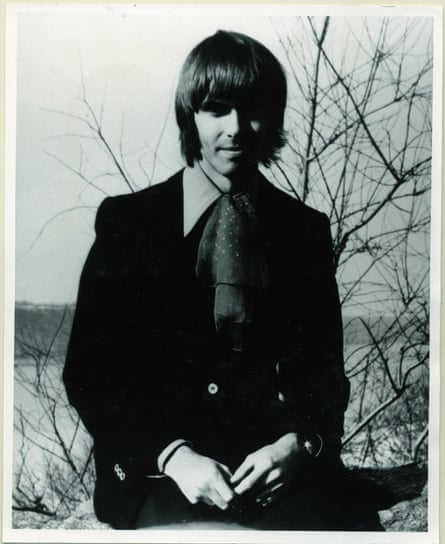

In each of those cases, the piano work sprang from the fertile mind and fleet fingers of Nicky Hopkins, a keyboard colossus so dexterous he gained eager employment from nearly every star of note from the classic rock world and beyond. Not only did Hopkins play with the Stones (on over a dozen albums in fact), he also worked with the Beatles, providing an iconic solo devised on the fly for their song Revolution. He also played on solo works by each of the Fab Four, including nearly every track on John Lennon’s Imagine album, and on classic sets by British bands from the Kinks to the Move, and American acts like Jefferson Airplane and the Steve Miller Band. More, he was a member of two key bands: the Jeff Beck Group with Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood, and Quicksilver Messenger Service, who helped define San Francisco psychedelia in the 60s.

“In all, Nicky played on over 250 albums,” said Michael Treen, who has directed a new documentary about the pianist titled The Session Man. “But he’s still not known by most people. There’s so much that Nicky contributed to music that he never got proper recognition for.”

In some cases, he didn’t get proper financial compensation either. Though the movie fairly bills Hopkins as a session man, his contributions to some songs he played on proved so key to the cut’s composition, he deserved a co-writing credit. “Nicky wasn’t just playing on the song,” Treen said, “he was helping to shape it.”

Even so, at the end of Hopkins too-short life at the age of 50 in 1994, he had little to show for it. “He was living in a small two-room apartment in Nashville and his wife was a waitress,” said Julian Dawson who, in 2011, published a book titled And on Piano … Nicky Hopkins. “He deserved so much more.”

To illustrate it, Dawson included in his book a copy of a receipt from EMI Records detailing the royalties Hopkins received for his featured work on the Beatles’ Revolution. “He got six pounds ten shillings for that session,” Dawson said. “I can’t think of a more eloquent way to show the unfairness of it all.”

Achieving financial equity wasn’t the only unfair element in Hopkins’s life. From youth, he suffered from Crohn’s disease, a poorly understood and incurable ailment that plays havoc with the digestive system. As a result, Hopkins was sickly and rail-thin for all of his life, ultimately leading to an early death.

Such darker realities in Hopkins’s life are underplayed in Treen’s documentary. “This isn’t a warts and all film,” the director admitted. Instead, he set out to celebrate “a man whose hands were full of magic”, he said.

That magic showed nearly from birth. “His mother can remember him at age three, reaching for the piano keys,” Dawson said. “That’s what people said about Mozart.”

In the Middlesex home where he grew up, Hopkins played classical music so fluidly that, by his teens, he won a scholarship to attend London’s Royal Academy of Music. At the same time, his older sisters had fallen in thrall to rock’n’roll, drawn in particular to piano-based artists like Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis. By 16, Hopkins was studying classical music by day and rocking out at night in shows with a band led by the British eccentric Screaming Lord Sutch. What made his playing stand out, besides his dashing fingerings and depth of feeling, was his unlikely melding of influences. “Somehow this young man, born in a suburb of London who played classical music, had the ability to channel Chicago blues and Memphis rock’n’roll,” Dawson said. “He could sight-read but he could also rock.”

At the same time, a mysterious illness haunted and ravaged him, leading to a stay in the hospital when he was 19 during which the doctors cut out parts of his intestines, nearly killing him. “After that, he felt he couldn’t tour any more,” Dawson said. “So, he went into the session world.”

Some of his first studio credits were with foundational Brit rockers of the mid-60s like the Kinks and the Who. He was hired for those sessions by the early producer of both bands, Shel Talmy. “I was told by another musician that I need to check Nicky out because he’s great,” Talmy said. “I did and he was. He always played exactly the right thing for what I was trying to achieve without me ever having to say, ‘do this or do that.’ He just seemed to know.”

Hopkins began working with Talmy and the Kinks on all but one track on their 1965 album The Kink Kontroversy. The next year, the band leader, Ray Davies, wrote a song for him titled Session Man, though its lyrics referred to the aloof sort of player who did studio work just for the money, as opposed to Hopkins, who loved the music and was loved by the bands in return. By the end of his sessions with the Kinks, however, Hopkins had a falling-out with Davies, whom he felt took credit for playing piano work he actually provided.

By contrast, he got on so well with the Who, they gave him a co-writing credit on their instrumental piece The Ox from their debut album, My Generation. “There’s an amazing passage in the song where the band drops out without telling Nicky they were going to do so,” Dawson said. “Nicky just carries on by himself for several bars while keeping the frantic tempo perfectly.”

Small wonder, the Who asked him to join the band, an offer he turned down mainly for health reasons. Besides, he was very much in demand for other sessions, not only because of the fleet variations he could innovate on the spot but because of his technical expertise. “Back when Ritchie Blackmore was still doing sessions in London [before his time with Deep Purple], he told me that if a producer came in and said, ‘sorry guys, we’re changing keys,’ the musicians would panic,” Dawson said. “Then they’d turn to Nicky who could immediately transcribe it for them.”

Another draw for Nicky was his likability and lack of ego. “He could come into the studio and offer whatever the song needed, rather than saying, ‘here I am, feature me,’” Dawson said. “He would find these magical spaces between the guitars that would wind up filling out the song.”

Talmy was so impressed by Hopkins’s work, he even produced a solo album for him in 1966 titled The Revolutionary Piano Work of Nicky Hopkins. The keyboardist’s studio work with the Stones began in 1967 for the album Their Satanic Majesties Request and escalated during a fraught and opportune time in their history. As Brian Jones was becoming more addicted to drugs, Hopkins’s contributions grew. In the single She’s a Rainbow, his piano and harpsichord provided the entire melody. Two years later, the Stones’ track Monkey Man opened with a mysterious piano trill that not only provided an indelible hook, it also set up the song’s haunting allure. In an interview for the documentary, “Keith Richards almost admitted that Nicky was responsible for a lot of Stones’ songs,” Treen said. Even so, all those pieces were credited to Jagger/Richards. When Dawson pressed Richards about that point for his book, he said the guitarist shrugged and said: “Well, that’s the Stones for you.”

In 1968, Jimmy Page, who knew Hopkins well from his own prolific session days, asked him to join Led Zeppelin. He declined because, at the time they were still known as the New Yardbirds and he didn’t think they were going to fly. Instead, he joined Jeff Beck’s group because they were about to tour the US, which had long fired his imagination. A gorgeous piece he wrote for Beck’s group, titled Girl from Mill Valley, captures his compositional sweep. Though Beck’s group imploded on that tour, Hopkins stayed in the US, landing on the west coast, where he became a key member of its psychedelic scene. He played the elaborate piano work on Jefferson Airplane’s Volunteers album and appeared with them at Woodstock. He enjoyed a rare co-writing credit with the Steve Miller Band on their elegant track Baby’s House and then joined Quicksilver, awarding what had been a twin guitar-driven band a piano that rivaled both. A nine-minute song he composed for Quicksilver in 1970, Edward, the Mad Shirt Grinder, featured lightning speed piano runs and jazzy breaks that made it an FM radio staple.

“It’s incredible to think that Nicky was not only an important part of the most inventive time in the London music scene of the 60s, but also affected everyone on the west coast American scene as well,” said Peter Frampton, who met Hopkins when they both played on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass album in 1970.

Later, Frampton hired Hopkins to perform on his early 70s solo album Something’s Happening. “Nicky played on two songs and turned them both into piano songs,” Frampton said with a laugh. “In both cases, he was the most interesting part of the song.”

Though the quality of his work remained exemplary, Hopkins fell deeply into drugs and alcohol in the 70s, partly inspired by the need to numb the pain of his illness and partly as an outgrowth of his touring life with Stones during the peak of their debauchery. “He was the wrong guy to be doing that stuff,” Dawson said. “Unlike Keith, he just didn’t have the strength to carry it off.”

On a later tour with Joe Cocker, “Nicky managed to get kicked out of the band for drinking too much,” said Dawson. “That’s a real achievement in that company!”

Though Hopkins cleaned up his act later in life, he remained frail, requiring periodic hospitalizations. His prime period of work had passed, though he still got lower-profile jobs and had some success in Japan in the world of film soundtracks. The Stones pitched in later by paying some of his mounting medical bills, but a botched surgery led to his death sometime later. “Essentially, he died of a heart attack caused by the pain,” Treen said. “The pain came from gangrene in his stomach caused by the operation. Even if he had survived the heart attack, who knows how far the gangrene had gone?”

As much classic work as Hopkins created during his lifetime, Dawson believes he had more to give. It pains him, and other observers, to know that the pianist is remembered today only by hardcore rock fans of the time. “I can’t think of another person who played on so many famous recordings and was such an important person in the studio,” Dawson said. “Nicky may not have been the one who was out there on stage or on the red carpet, but he was key to everything.”

-

The Session Man is now available to rent digitally in the US with a UK date to be announced

Source: theguardian.com