Alice is no longer residing in this location.

I will leave it to others to debate Scorsese’s views on gender. His lack of female characters has been a source of criticism for feminist movie enthusiasts, and when he does include them, they are often portrayed as wives or objects. However, in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, a charming romantic comedy starring Ellen Burstyn as a middle-aged woman reinventing herself in a male-dominated world, this is not the case. After her husband’s sudden death, Alice and her witty preteen son embark on a journey to fulfill her childhood dream of becoming a lounge singer. As expected, she encounters unpleasant men along the way, such as sleazy club owners and a deranged, infatuated younger man (played by the crude Harvey Keitel). Despite this, Alice remains resilient and unapologetically sassy. During a job interview where a creepy bartender asks her to twirl, she delivers one of my all-time favorite lines that still resonates 50 years later: “Look at my face. I don’t sing with my behind.” Alaina Demopoulos.

Taxi Driver

During an interview with GQ about Killers of the Flower Moon, Scorsese expressed his sadness that Travis Bickle, the troubled and aggressive protagonist of his 1976 masterpiece, no longer embodies the idea of “God’s lonely man” that he and screenwriter Paul Schrader had intended. Scorsese reflected on the unfortunate reality that, nowadays, it seems normal for people to share similar traits with Travis Bickle. However, Taxi Driver remains a powerful film by delving into the mindset of a Vietnam veteran (played by Robert De Niro) who roams the streets of New York, fueled by racism and anger which eventually lead to a shocking outburst of violence. The irony of Travis being seen as a hero for killing a pimp instead of a politician continues to haunt a country that glorifies the idea of “good guys with guns”. In Scorsese’s perspective, we gain a deeper understanding of Travis’ true desire to simply kill.

The King of Comedy

It’s difficult to choose just one of Martin Scorsese’s many great films. “Raging Bull,” “Goodfellas,” and “Taxi Driver” are all masterpieces, with “The Wolf of Wall Street” being the most entertaining and “Mean Streets” being the most haunting. However, “The King of Comedy” is the film that I keep going back to. It remains the most unhinged, unexpected, and funniest of Scorsese’s movies. Made shortly after the murder of John Lennon, the film explores the increasingly dangerous relationship between celebrities and their fans. The basement chatshow set is still just as freaky as it was when the film was first released. While Robert De Niro is very funny as the main character with his silly mustache and blow-waved hair, his portrayal of a stalker may be a little implausible. Sandra Bernhard, on the other hand, shines in her role as a needy fan, and her performance still jumps off the screen. What makes this film so impactful, in my opinion, is its prescient insight into the societal breakdown that has consumed large portions of American society. This theme is even more relevant today. “The King of Comedy” is a timeless film that has not lost any of its relevance or impact.

After Hours

Do you believe you should go out more often? After Hours aims to change that belief. Martin Scorsese’s hectic and doomsday-esque 1985 film follows a professional word processor, Griffin Dunne, through one eventful night in the ominous and un-Sweetgreen-ed Soho. Initially, our protagonist, DTW, plans to spend the night at home until he realizes the world is a cruel place and decides to retreat under his covers. However, he is enticed out by a mysterious stranger, Rosanna Arquette, whom he meets at a diner. She invites him to her Soho loft, a large space shared with a tempestuous papier-mache artist, Linda Fiorentino. This impromptu visit leads to a series of disasters, including being mistaken for a burglar and being chased by an angry mob, and being unable to afford the subway fare back to his Upper East Side apartment. Scorsese’s film is a fusion of Hitchcock and Wizard of Oz that also provides a glimpse into the old Soho, with its wet streets and spacious lofts that were once affordable for those with messy lives and no LinkedIn presence. It also accurately captures the experience of being an insomniac. Lauren Mechling

Goodfellas

It may seem obvious and unoriginal to declare Goodfellas as Martin Scorsese’s greatest achievement, akin to stating the obvious about Sgt Pepper’s being The Beatles’ high-water mark. However, the film’s undeniable greatness allows us to take it for granted. Even without constant replays on television, the expertly crafted momentum of the film’s musical cues, freeze-frames, and dolly shots give it a timeless quality. Scorsese and his co-writer Nicholas Pileggi not only established numerous gangster tropes but also delved into the corrupt nature of the American dream through the portrayal of a ruthless wise guy like Henry Hill. Yet, the film’s surface appeal is just as important, as it heightens the impact of Hill’s eventual downfall.

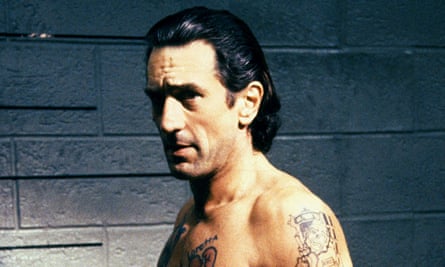

Cape Fear

Often unfairly grouped together with the more easily forgotten Shutter Island, 1991’s Cape Fear is a film that will leave a lasting impression. Released during the rise of domestic thrillers following Fatal Attraction, Scorsese expertly blends suspenseful entertainment with a weight and sophistication that is often lacking in similar subgenre films. While it may be enjoyable to watch Robert De Niro embody the despicable and violent rapist Max Cady, the film’s most explosive moments come from the family he terrorizes. Nick Nolte and Jessica Lange’s strained marriage only needed a small spark to ignite, and their intense arguments are riveting to watch. Lange also adds a raw and poignant depth to a monologue that is typically formulaic in these types of films – the killing of a pet. Additionally, Juliette Lewis gives an unsettling and captivating performance as the teenage daughter who falls under Cady’s dangerous spell. With a classic title sequence by Saul Bass and a haunting score by Bernard Herrmann (from the original 1962 film), the influence of Hitchcock is evident but Scorsese makes Cape Fear stand out as a truly original and terrifying experience. Benjamin Lee

The Departed

Martin Scorsese is undeniably an exceptional filmmaker, considered by many to be one of the greatest of all time – a fact that has been argued by countless individuals, perhaps even better than I could do so. However, I must confess that my primary incentive for watching a large portion of his works was due to my infatuation with Leonardo DiCaprio, which lasted from the time I first saw Titanic at the age of 12 until I turned 25 and realized that I was not as old as I believed. Out of all the collaborations between DiCaprio and Scorsese, my personal favorite – and the one I have rewatched the most times with the most enjoyment – is The Departed. Released in 2006, during DiCaprio’s prime years, it is a remake of the 2002 Hong Kong film Infernal Affairs. The Departed is a complex tale of deception, betrayal, and unlikely connections that, in theory, should not work. However, in Scorsese’s skilled hands, it becomes a seamless and captivating experience, almost like a magic trick. The film also features added bonuses, such as the powerful montage set to the Dropkick Murphys’ music, the vivid depiction of Boston, and a memorable scene of Leo passionately kissing Vera Farmiga on a kitchen counter. Scorsese maintains a tight pace and intense tension throughout the film, showcasing his precise directing abilities. Most importantly, it is a highly enjoyable viewing experience that stands the test of time far better than my teenage crush on DiCaprio.

The Wolf of Wall Street

Throughout his career, Martin Scorsese has displayed a preoccupation with the dramatic rises and falls of dangerous men. The Wolf of Wall Street, based on the true story of white-collar criminal Jordan Belfort, may be his most extravagant and Dickensian tale yet. From Belfort’s drunken helicopter crash onto his opulent golf course in the opening scene, to the sinking of his massive yacht off the coast of Sardinia, to the relentless hustling demonstrated in the film’s final scene, Wolf is a frenzied and perhaps satirical portrayal of toxic masculinity. Released during the time of Occupy Wall Street, the film could even be considered an improvement on Scorsese’s previous epics Goodfellas and Casino, as it invites viewers to laugh at these characters rather than sympathize with them.

Public Speaking

There is a clip of Fran Lebowitz talking about the demise of cultural connoisseurship that I can’t help but watch every time it crosses my timeline. Midway through Scorsese’s 2010 documentary Public Speaking, the critic, cynic and sometime Law & Order judge devastatingly argues that Aids led to a loss of a discerning audience for the arts. “Everything has to be broader,” she concludes. Public Speaking traces Lebowitz’s life in letters and walks alongside her in all weathers, but the heart of the film are her conversations with Scorsese, filmed beneath murals of bohemians and beatniks and animated by his warm laughter. She can be sniffy, barbed – as well as usually right. (I’m not sure how she concluded that all gay bars now have stained glass windows and a valet service, but most of her one-liners still hit.) In a filmography where the city is often a protagonist, Scorsese made a great New York movie by spotlighting one of the most singular characters within it. Owen Myers

Silence

Scorsese’s inner spiritual journey is fully depicted in his later masterpiece, which combines elements of The Last Temptation of Christ and Apocalypse Now. Silence, based on Shūsaku Endō’s novel, is a story of Jesuit priests in 17th-century Japan who must learn to listen and understand the people they are trying to preach to, rather than relying solely on scripture. The main character, Rodrigues, played by Andrew Garfield, struggles with his faith and seeks divine guidance in a seemingly barren land. Scorsese, along with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, beautifully captures the essence of Endō’s text through stunning and unforgettable images. The white fog symbolizes clouded judgement, Rodrigues sees reflections of Christ and his own ego in a river, and the overhead fisheye shot highlights the oppressive hierarchy of religious institutions. Radheyan Simonpillai

The Irishman

As a fellow movie enthusiast, I find it frustrating when diehard superhero fans and others dismiss Martin Scorsese as only a director of gangster films. While that may be one aspect of his work, he has also made impactful movies in various other genres, such as adaptations, children’s films, religious epics, and documentaries. Despite this, I cannot deny that The Irishman, his recent film focusing on career criminals, is a personal favorite of mine. It is best viewed in one sitting, as the story unfolds with Scorsese’s signature elements of dark humor, betrayal, and powerful performances. As we follow the protagonist Frank Sheeran (played by Robert De Niro) on his inevitable journey towards death, we are reminded of the importance of holding onto our humanity. Like life itself, Scorsese’s film is long but also ends too soon.

Source: theguardian.com