This week sees the release of Heretic, Hugh Grant’s 45th feature film. Few critics would have predicted that length of career after his pouting 1982 debut in Privileged, a pretentiously shonky whodunnit featuring several of his fellow Oxford students. For the next decade he wasn’t so much a fringe actor as an actor with a floppy fringe, invariably cast as a posh, slightly foppish Englishman, doomed to be forever brushing his lustrous hair back from his finely chiselled features.

Then 12 years on everything changed with the release of Four Weddings and a Funeral. More accurately, the floppy fringe remained, but now it was employed as comedy cover for a strikingly diffident kind of romantic hero. Overnight Grant was catapulted into the realm of international fame, going on to co-star with his haircut in a series of not wildly dissimilar romcoms.

A horror film, Heretic is a world away from all that. Grant is now 64, the curtain mop is long gone and the boyish charm has matured into something far more dangerously charismatic.

He plays Mr Reed, who is driven by a provocative yet pitiless logic, and betrays more than a touch of evil. It’s not his first bad guy. He’s been flirting with villainy for a while in films like Paddington 2 and Dungeons & Dragons, not to mention his suavely ruthless Jeremy Thorpe in the much-lauded TV drama A Very English Scandal.

Mr Reed, though, occupies much darker territory. Grant said recently that the role is part of “the freak-show era” of his career. The change in direction has suited him, not least because a roguish character, as he’s made a point of saying, is closer to his own.

The stammering toff who seemed to have fallen out of an early Evelyn Waugh novel was his party piece, and it was used to brilliantly subversive effect in Roman Polanski’s Bitter Moon, which predated Four Weddings. But it was perfected for Richard Curtis and it became his go-to public persona.

As he told the New York Times: “I thought if that’s what people love so much, I’ll be that person in real life, too.”

That job grew much more challenging after his arrest in June 1995 following a brief encounter in a BMW on Sunset Boulevard with sex worker Divine Brown. His timid romantic act appeared to have been dealt a fatal blow, but Grant doubled down, dealing with the fallout in character, as it were.

The nervous young man who squirmed in the Tonight Show armchair while Jay Leno asked: “What the hell were you thinking?” managed to perform a delicate piece of image repair. In this endeavour he was ably supported by his then girlfriend, Elizabeth Hurley.

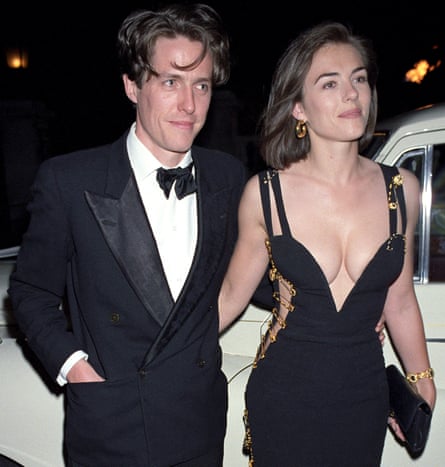

With her photogenic looks and preference for well-ventilated clothing, Hurley had become a fixture in the UK press, making the couple a red-carpet dream team. The attention they drew would later have far-reaching repercussions when Grant discovered what press intrusion really entailed.

The sordid sex crisis deftly negotiated, Grant’s star continued to rise in a trio of Curtis-scripted films: Notting Hill, Bridget Jones’s Diary and Love Actually.

It was in the middle one, in which he played the caddish Daniel Cleaver, that Grant began to grow as a comedic actor, famously ad-libbing some of the film’s best lines. Next year he reprises Cleaver in the fourth Bridget Jones film, Mad About the Boy.

“I think he did feel apprehension about stepping out of that floppy, tongue-tied English character,” recalls Bridget Jones’s Diary director Sharon Maguire. “I remember him being really pleasantly surprised and relieved the first time he saw the movie at the New York premiere … and only a teensy bit jealous that Colin Firth got just as many laughs.”

after newsletter promotion

The making of that film coincided, roughly, with his breakup with Hurley. There followed a prolonged period of intermittent dating and an ever-more fractious relationship with the tabloids. The key text of this period is About A Boy, in which he plays a man in flight from romantic commitment. Grant acknowledged that he put a lot of himself into the role.

Yet suddenly, in his 50s, the confirmed bachelor contrived to father two children who are now 13 and 11 with the actor Tinglan Hong, and in between a son with Swedish TV producer Anna Eberstein, with whom he had two more children and to whom he has been married for six years.

Grant, whose father was an ex-army officer who worked in the carpet business and mother a French teacher, had originally wanted to be a writer. Although he more or less fell into acting, he’d always been a performer. Old schoolmates at Latymer Upper School in Hammersmith, West London, still talk of his mesmerising recital of Eliot’s The Waste Land.

But without formal drama training or a background in the theatre, Grant, even by the neurotic standards of most actors, nurtured a deep streak of professional insecurity – he has complained of being paralysed by panic attacks when filming.

“I got the strong impression,” says Maguire, “that Hugh was filled with loathing at his own acting and yet he was hugely conscientious about the process of acting, a perfectionist who often contributed gold in terms of the comedy and authenticity of a scene.” His exacting approach to work has not always won him friends on set. Robert Downey Jr called him a “jerk” after they made Restoration together in 1995. And Jerry Seinfeld, who directed him in Unfrosted, was only half-joking when, earlier this year, he described Grant as “a pain in the ass to work with”.

For all his self-criticism – he’s said that people were rightly “repelled” by his stumbling Englishman character – Grant also knows his own worth, not just financially but also in terms of industry longevity and position. The man who appears nowadays on talk shows with his well-honed anecdotes and waspish self-deprecation is a supremely confident veteran of the business of selling himself.

There’s also an added steeliness, a disinclination to suffer fools, that has been sharpened in the legal battles waged since he learned that his phone had been hacked by the now defunct News of the World. A leading figure in Hacked Off, the campaign group that seeks reform of press self-regulation, Grant settled a lawsuit with the Sun this year, having accused the paper of hiring a private investigator to break into his flat and bug him.

He said on X that he would have liked to go to court, but if he’d been awarded damages that were less than the settlement offer “I would have to pay the legal costs of both sides”, which he said could be as much as £10m, adding: “I’m afraid I am shying at the fence.”

Taking on Rupert Murdoch is one thing, but Grant is also not averse to showing his tetchier side to those lower down the media ladder. Last year his stilted interview with model Ashley Graham on the Oscars red carpet inspired almost as much condemnatory newsprint as his other Hollywood interaction three decades earlier with the unfortunate Brown.

When asked what he thought of the event, he compared it to Vanity Fair. He meant the Thackery novel, but Graham assumed it was the magazine after-party. The conversation only went downhill from there. Grant was derided as a snob and self-important, though it’s fair to say that some of his fanfare-deflating drollery was lost in cultural translation.

Then again, maybe he wasn’t just bored with banality but instead, with one eye on his career, he was establishing his new edge in the public imagination. With Grant it’s impossible to know. His real motivations and character are buried beneath geological layers of artifice, irony and a highly developed celebrity defence system.

He could probably write a wonderfully scabrous exposé of the film world and himself in the tradition of David Niven and Rupert Everett, but it’s far more likely he’ll concentrate on the job in hand: gradually occupying the position of a national treasure.

Source: theguardian.com