‘The acid house scene in Liverpool in 1988 was really tiny,” remembers Sonia Martelli. “You could recognise each other because we were all wearing smily face T-shirts and we’d be at the same night.”

And once that one acid house night had ended – Daisy, run by James Barton, Andy Carroll and Mike Knowler at the State – there were even fewer options for ravers to keep going. “People would break into disused warehouses or old supermarkets in Toxteth,” recalls Martelli, one half of the DJ duo Girls on Top. “There was another place we called the Scrappy, which was a rave in a scrap yard.” Another party was held in the abandoned Tate & Lyle sugar refinery: it was such a vast space that when the police turned up it would take them so long to reach the ravers at the other end of the building, they had enough time to pack up their PA into nearby trucks and scatter.

The story of Liverpool’s nightlife is usually dominated by Cream, founded in 1992 and held at Nation – an underground night turned global mega-brand. But by then, the city was already an epicentre for clubbing. This pre-superclub era – energetic, euphoric, eyed-up by police – is being revisited in October with a reunion for Merseyside institution Quadrant Park, which should be spoken about in the same breath as Manchester’s Haçienda: a daringly uninhibited champion of north-west rave culture.

During 1988 the scene became so energised, in fact, that it threatened to burn out before it even got going. “It had suddenly erupted and went completely off the scale in no time at all,” says Martelli. The State was already closed by 1989. “We were the first victims in the city of the acid house exterminators,” recalls Carroll. “The same old thing where a licensing cop comes in and wants to make his mark.” He even alleges that during this period they were so keen to shut down this new swell of giddy activity that his phone was tapped and he was followed by police.

Barton managed to keep the party going, joining forces with John Kelly to open the equally influential club the Underground, hosting memorable sets by the likes of Adamski and Guru Josh. But the most powerful detonation during this era was to be felt at Quadrant Park, in the small town of Bootle, north of Liverpool.

Built in a converted warehouse, it was a typical chrome-and-carpets nightclub that was quickly fading into irrelevance. After DJing a Christmas party there, Knowler took up a residency in January 1990. Far away from the glare and focus of Liverpool city centre, nestled in the industrial docklands, Carroll joined him and soon they were throwing electric parties where around 2,500 people were flocking to hear the uplifting sounds of acid and Italo house. “It felt pirate,” says Carroll, who is DJing at the Quadrant Park reunion in Liverpool alongside Knowler and Kelly. “Like being cheeky outlaws who were getting away with it.”

They largely were – a legal loophole meant the snooker club above the nightclub could function as a 24-hour private members’ club. “People were then made members when they arrived,” says Carroll. This meant that the Quad, as it was known, would become one of the first legal all-night raves in the UK.

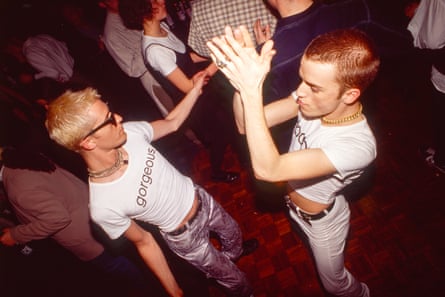

Over the next year, the likes of Derrick May, Laurent Garnier and Joey Beltram all DJed, with live PAs from artists such as LFO and Nightmares on Wax. There’s a recording taken inside the club in 1990 as the house track Anthem by N-Joi is playing: a goosepimple-inducing depiction of pure, crystallised dancefloor release. “It was like that every night,” says Girls on Top’s Martelli. The other half of the duo is Jill Thompson, who recalls: “It was completely nuts from the first record that was played through to the end.” Photographer Mark McNulty remembers it as pandemonium. “The whole place, every single inch, was dancing,” he says. “On the speakers – everywhere.”

Saffron, the singer on the rousing N-Joi track, was at the Quad regularly to perform it live. “It was an almost supernatural place,” she recalls. “To this day, I don’t think we’ve ever had such extraordinary crowd reactions.” Carroll says that “it felt like every other tune you played was received like your favourite team had just scored a goal. At the end of the night, there would be whistles, sirens and cheers just going on and on and on. I’ve DJed all over the world and still not experienced anything like that.”

By the end of that year, the remaining part of the warehouse had been converted into a space called the Pavilion and overall it could now hold 5,000, essentially becoming a template for what would become known as the superclub. However, with the increased capacity came the usual problems with drugs and crime. “I felt the owner wasn’t taking the right precautions,” recalls Carroll. “Corruption flew in and you had all sorts going on.” Carroll and Barton left to run the slick purpose-built 051 club in 1991 and the Quad was finished by the end of the year, as interest waned and trouble spiked.

But while it was over all within less than two years, at its peak it remains an incomparable place for many. Thompson recalls managing the Russian group the New Composers, whose 1990 track Sputnik of Life was a big hit at the Quad. “I brought them there so they could see the response to their track in the biggest, maddest club in the country,” she recalls. “And they were just sitting there stunned, practically in tears.”

Just as pivotal to many around this time were the homegrown house tracks put out by Eight Records, the nights G-Love and Icon, the nightclub Garlands, and the Girls on Top duo who were creating “the most inclusive place you could have” at their all woman-run night Froot. Given many of the key people from Quadrant Park were involved in the initial formation of Cream – Barton and Carroll, along with Darren Hughes – they had learned valuable lessons and were able to whip Cream into a slick, professionally run operation: coachloads of people from all over the UK soon came to sample the new style of superclub. However, in 1993, as Cream began its rapid ascent, another club became just as significant for many others, with Voodoo favouring a harder and rawer style of music than the more commercial house sounds heard at bigger clubs.

Hosting DJs such as Richie Hawtin, Jeff Mills and Carl Cox, this nightclub would go on to play a role in the hugely successful rave-influenced computer game, WipEout, which was being designed at the time by Psygnosis, a Liverpool-based game developer. “We had a dedicated posse of the development team that would frequent Voodoo,” recalls Nick Burcombe, who co-created the game. “It was the best underground music in Liverpool by a mile. It was more like being in Berlin but without the hassle of the airport. I didn’t want a dress code and superstar DJs – I wanted something dark, sweaty and relentless.”

CJ Bolland, who played some legendarily pummelling sets at Voodoo, recalls it as being a place that felt like “our underground world” and “while you sensed it was special, you didn’t know that it was going to turn out to be one of those clubs that was legendary.” David Holmes, who would later become a resident, calls it “one of the great clubs of the 90s”.

However, there wasn’t necessarily a purist versus tourist mentality in the city as dance music went stratospheric. “It’s a luxury to have something that’s underground and intimate where you know everyone in the room,” says Girls on Top’s Thompson. “But it can’t last. If it’s brilliant, it’s gonna go mainstream and you just have to embrace it. It brought students here and boosted the economy. And, trust me, in the 80s it was grim. There was just no money and now Liverpool is looking its best. House music was a magnet to help make that happen.”

While much of the narrative around UK dance music history has overlooked some of the vital contributions Liverpool made during this era, for Martelli there’s a direct through line from partying in filthy skips in the freezing cold night, or running away from police in abandoned sugar factories, to today. “We were told at the time, oh it’s just a blip and that we’d all go away. But we’re still here,” she says. “Just look across the world. Dance music is pop culture.”

Source: theguardian.com