The song begins with a barrage of power chords, brazenly stolen from the Who’s Won’t Get Fooled Again. The opening lyrics are mewled out in an estuary accent: “I get bored so easily – that’s why I only say hello.” And the list of influences from here includes the Sex Pistols and Ziggy Stardust-era Bowie – before it ends with a brazen lift of the coda from the Beatles’ version of Twist and Shout. When it gets to the chorus, everything becomes clear: this is a ferocious, wonderfully camp blast against the stifling cultural dominance of classic Americana: “Goodbye Jimmy Dean, don’t tell me what to wear / See you later Monroe, if anybody cares.”

All this might suggest a lost classic from the mid-1990s, and the gaudy wonders of Britpop. But Goodbye Jimmy Dean was actually by Boys Wonder, a visionary band whose star rose and fell between 1986 and 1988. They were about eight years ahead of their time, and in retrospect, their chronically awkward fit with their era was probably always going to be their undoing. But while they lasted, they were great. In 1987, I saw them performing on the Channel 4 comedy show Saturday Live, swaggeringly delivering another three-minute manifesto titled Shine on Me. I was smitten, but given their large-scale blanking by the music press (and the fact that the world wide web had yet to be invented), I was left wondering what on earth had happened to them.

Now I know. Boys Wonder released only four singles. Goodbye Jimmy Dean was the third, put out before the loss of key members and an ill-advised detour into more dance-influenced music. Even at the band’s peak, journalists were largely indifferent or hostile, and their songs were barely played on the radio. As their singer Ben Addison now puts it: “We were banging our heads against a wall. And the wall won.”

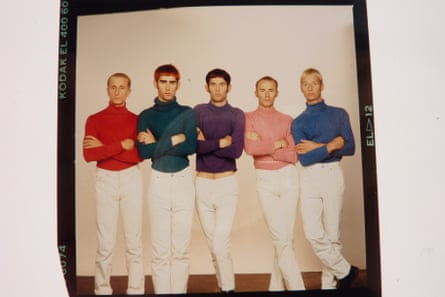

Now their prescience might finally be acknowledged. The band’s quintessential five-piece lineup have just performed their first gig in 35 years, with another to follow. At the same time, some of their original stage outfits feature in Outlaws, a new exhibition centred on “fashion renegades of 80s London” at the capital’s Fashion and Textile Museum. But the main event is a brilliant new Boys Wonder anthology titled Question Everything, most of which has never been heard before.

In the course of a fascinating two-hour Zoom call, Addison – who is now a father of two, resident in Dusseldorf – tells me the band’s story. He and his twin brother, Scott, were art-school alumni from south-east London, who cut their musical teeth as the drummer and bassist with a quartet called Brigandage (“the Sex Pistols with a female singer,” he says), in the vanguard of a short-lived genre known as Positive Punk. Once that project had come to grief, they befriended guitarist Graham Jones, who was about to exit the wreckage of early 1980s pop sensations Haircut 100. He and the Addisons shared a vision of the best punk rock being mixed with a dazzling array of other influences.

Jones, who speaks to me from his home in Cornwall, recalls daily trips to the Addisons’ flat, where the three of them would meticulously record songs using a four-track Portastudio. “While Scott was doing his overdubs,” he says, “Ben would be sitting over in the corner with a pad and paper and he’d be drawing outfits. Our girlfriends were going to fashion college, so some of them could create the items of clothing that Ben was drawing. There was more going on than just the music: this whole creative process was happening behind the scenes.”

They soaked up as much of their favourite music – and its iconography – as they could. “We would sit down together and watch the Who do My Generation on [1960’s US TV staple] The Smothers Brothers show,” says Addison. “The [Pistols’] God Save the Queen video. Untold Bowie stuff. Roxy, especially with the shoulder pads and Brian Eno’s feathers. Tom Jones when he was at his most gyratable, as it were. And pre-fat Elvis.”

There was an early plan to call the band Batman & Robin, but the expectation of copyright problems led them to put an ‘s’ on the latter character’s “Boy Wonder” tagline, and the resulting name stuck. A visual breakthrough came with the Addisons’ bowl-contoured haircuts, which defied the 80s’ tyranny of quiffs. “A good friend of ours called Andrew McLaughlin was a rising star within Vidal Sassoon,” says Addison. “He turned up one night at the Greenwich theatre bar, which was one of our favourite hangouts, with this bleached, completely severe fringe, like Henry V. He looked like something out of black and white Doctor Who. I said, ‘Fucking hell, Andrew – that is the bomb. This is what we’re going to do.’” Ben combined his new barnet with eyebrows almost comically thickened with an eye-pencil, and instantly had his signature look.

“It just felt just so exciting, to be doing something that no one else was doing,” says Jones. They soon attracted the attention of Seymour Stein, the legendary American impresario who had previously signed the Ramones, Talking Heads and Madonna to his Sire label. After working with the Smiths, the Cure and Depeche Mode, Stein was looking for more talent from this side of the Atlantic, albeit without much of a budget.

“We were doing night-time recording sessions,” Addison tells me. “And one night, on the phone, we asked him for some more money. There he was, on a lounger in some Vegas pool with a cocktail, but he told us we were living in a dreamworld by asking for a bit more. To coin the cliche, I think we really were more of a tax write-off than anything else.” So it was that their time as a major-label act abruptly came to a close; a short spell with the Rough Trade label proved no more successful.

after newsletter promotion

The new anthology shows that in the midst of these disappointments, Boys Wonder’s music was consistently superb. If they had a defining sound, it was the meld of punk, glam and perfect pop aesthetics that cohered not just on Goodbye Jimmy Dean and two other singles – Shine on Me and Now What Earthman? – but other songs whose titles illustrated the singular thinking at work: Lady Hangover, Baby It’s No Joke, We All Hate Honesty. The other side of their creative universe took its lead from English musical theatre, as evidenced by such songs as Soho Sunday Morning, such an augury of the turn British music would take in the 90s – right down to its parping brass – that it now sounds downright prophetic.

Which takes us back to Britpop. By the mid-90s, the Addison twins had formed Corduroy, a quartet signed to the Acid Jazz label who retained a London-centric sense of place, but mixed it up with everything from 60s film soundtracks (their first two albums were largely instrumental) to Steely Dan. They now watched as Blur, Suede and Pulp – as well as the era’s countless wannabes – seemingly walked in Boys Wonder’s footsteps. To some extent, the same could be said of Oasis, certainly when it came to their shameless plundering of rock history.

“If I hadn’t been doing Corduroy, then I’d probably have been a bit more depressed,” Addison tells me. “I’m not trying to put anyone down: Blur, for example, used to use Corduroy’s song London, England as their intro tape. They asked us to do their Alexandra Palace gig [in October 1994], so I’m indebted to them for that.”

There is another Britpop connection: Addison says he remembers a gig at the University of London Union (AKA ULU), where the polarities were reversed: Boys Wonder were supported by the nascent Blur, who were then called Seymour. “I don’t want to claim anything,” he says. “But that’s what happened. There was a proximity between the two things … it felt very strange because Britpop was so unglamorous. Adidas shell toes, Adidas fucking T-shirt. What? For me, that was the main difference. No style. It was just scratch-the-surface thinking.”

Like his Boys Wonder colleagues, Addison – who still makes music, and is also a visual artist – is now in his early 60s. When we speak, the band is about to play its first reunion show. “On the downside, I’m way older now,” he says. “I’m not jumping about as much. I’m not going to do the eyebrows or anything like that. So there’s trepidation over that. But it’s boogied out of the way by the confidence in the songs, which is renewed.”

Returning to their old glories, in fact, has prompted him to try to turn the classic generation gap on its head. “I’m not on a mission,” he tells me, breaking into a grin. “But I think if there is anything to be pointed out, the message is: your grandparents were way more interesting than you are.”

Source: theguardian.com