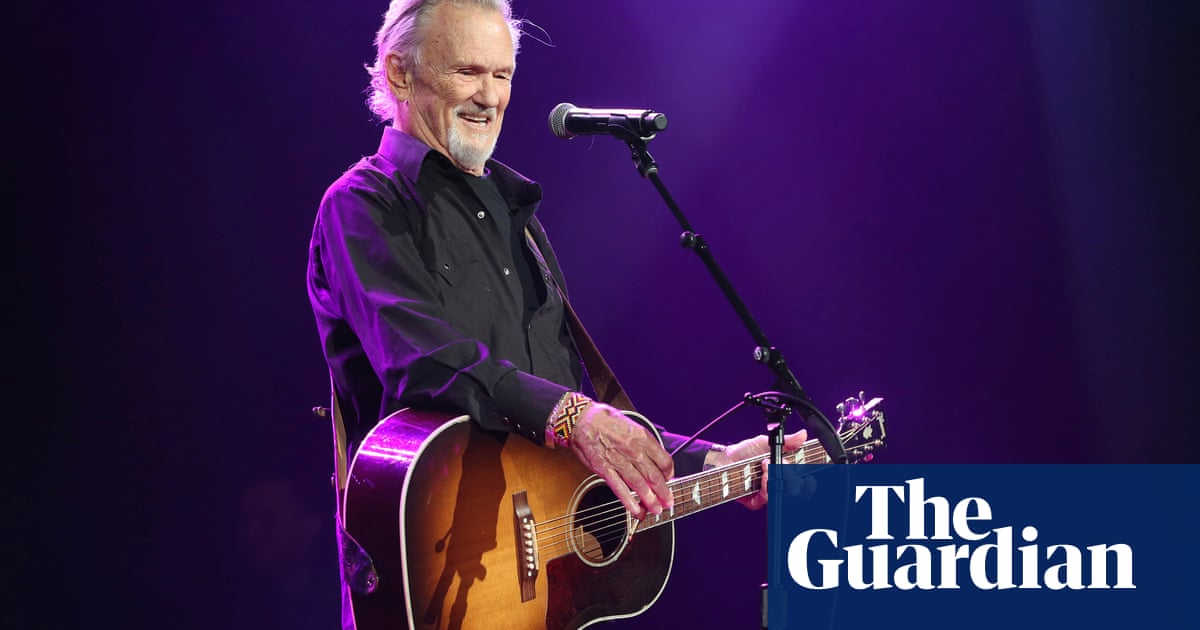

Me and Bobby McGee (1970)

One of the great American songs – evident from those who have covered it, including Janis Joplin, Dolly Parton, Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash and the Grateful Dead – was written by Kris Kristofferson and first a hit for Roger Miller. It’s a perfect road song, inspired by Fellini’s La Strada, and encapsulates Kristofferson’s voice: bruised and desolate, but romantic and hopeful, with a markedly masculine streak. (Kristofferson neither looked nor sounded metrosexual; his sensitivity was not uncomplicated.) It’s hard to imagine a song with such a perfect opening verse (“Busted flat in Baton Rouge … feelin’ near as faded as my jeans”) could deliver on its setup, but Me and Bobby McGee does, with its single devastating line: “Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose.”

Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down (1970)

Kristofferson called this the song that enabled him to stop working for a living and he was shocked by how many of his heroes admired it. It’s very simple: a man recounts his hangover. But as the verses accumulate, it becomes evident that the singer’s pain isn’t just a crushing headache, it’s a deep sense of loneliness. The details he notices are the things he doesn’t have – playing children, a sense of joy – and when he pleads, “On the Sunday morning sidewalks / Wishing, Lord, that I was stoned,” he’s not looking for relief from his hangover, but for something to stop him having to enter his own void. No wonder Johnny Cash had a No 1 hit with it.

To Beat the Devil (1970)

In the spoken intro to To Beat the Devil, Kristofferson made his debt to Cash clear: “I’d like to dedicate this to John and June, who helped show me how to beat the devil.” Like Cash, Kristofferson sang country but was also part of the counterculture. To Beat the Devil took one of music’s great myths – the singer who sells his soul for the song – and upended it: “I ain’t sayin’ I beat the devil, but I drank his beer for nothin’ / Then I stole his song.” It’s not the literal devil, of course: this is Kristofferson saying he managed to better the music industry and his own demons.

Help Me Make It Through the Night (1970)

The story goes that an Esquire interviewer asked Frank Sinatra what he believed in. “Booze, broads, or a Bible – whatever helps me make it through the night,” he replied. And from that line Kristofferson conjured his most enduring hit. It’s a love song that isn’t a love song – the singer doesn’t want to give, only take (even if they say “All I’m taking is your time”). They do not care about right or wrong, they do not want to understand. They want only to be held. It’s surprisingly complex, about dependency more than commitment.

The Pilgrim, Chapter 33 (1971)

Another song for his heroes – named in the intro and including Cash, naturally – which portrayed a mythical country singer in all his contradictions. The Pilgrim, Chapter 33 makes the life of a travelling musician sound less like a job than a calling that will torture all those who answer. One line captured the complexities of being a songwriter, for what is a songwriter but a maker of promises to their audience? “Never knowin’ if believin’ is a blessin’ or a curse / Or if the goin’ up was worth the comin’ down.” Bruce Springsteen would later get an awful lot of mileage out of exploring that precise notion.

Jesus Was a Capricorn (Owed to John Prine) (1972)

Much lusher than his earlier recordings – perhaps inevitable, given Kristofferson’s technical weaknesses as a singer – Jesus Was a Capricorn notes that if Jesus was resurrected, he’d promptly be nailed back on the cross. And so it goes across society: “Eggheads cursin’, rednecks cussin’ hippies for their hair / Others laugh at straights who laugh at freaks who laugh at squares.”

Nobody Wins (1972)

A simple and stark heartbreak ballad, performed by Kristofferson as a sleepy country blues – the organ that sustains it is a deep, deep blue – but it’s sufficiently malleable that it didn’t have to stay that way. The king of the heartbreak ballad, Sinatra, recorded it in 1973 on Ol’ Blue Eyes Is Back. It’s not an insult to Kristofferson to say that when you hear one of the greatest voices in pop history sing his words – even when they are draped in saccharine strings – you hear the absolute resignation in the lyric: “The loving was easy / It’s the living that’s hard.”

From the Bottle to the Bottom (with Rita Coolidge) (1973)

Kristofferson married the country singer Rita Coolidge shortly before they released their first album together, Full Moon. From the Bottle to the Bottom has a glorious Cajun swing beneath the honky-tonk, and one of the classic country storylines: She’s gone, I’m drinking. The sharpness of Kristofferson’s writing makes it more than just another cliche: “Did you ever see a down and outer waking up alone / Without a blanket on to keep him from the dew / When the water from the weeds has soaked the paper / He’s been puttin’ in his shoes to keep the ground from comin’ through.”

Here Comes That Rainbow Again (1982)

Just as he span a song out of a line in someone else’s interview, so he conjured Here Comes That Rainbow Again from a short scene in The Grapes of Wrath. The doominess of the waltz undercuts the message, which is about showing kindness: a truck stop waitress undercharges kids for sweets, and then is overtipped in turn by a pair of truck drivers. So why the doominess? Perhaps because even simple kindness raises suspicions: “So what’s it to you?” the benefactors point out when asked about their generosity.

Closer to the Bone (2009)

This may not actually be one of the 10 best Kristoffersons, but it’s worth remembering that singers and writers grow old and their preoccupations change. Closer to the Bone is the sound of a man making peace with his past as the end approaches, looking back and feeling no shame, because “Everything is sweeter, closer to the bone.” It’s nice, too, to hear his voice – now a growl – backed by raw instrumentation: acoustic guitar, banjo, fiddle, harmonica. Here is Kristofferson in raw form.

Source: theguardian.com