E

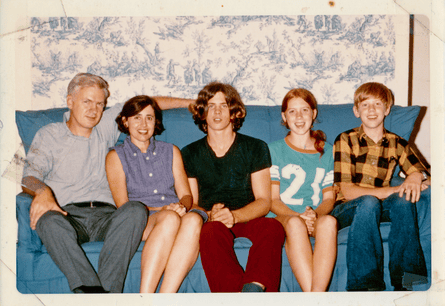

In the early stages of his memoir, Sonic Life, Thurston Moore recalls a tumultuous period during his teenage years that could have ended disastrously. Under the influence of an older friend who had a penchant for trouble, he engaged in a short but remarkable stint of juvenile delinquency. This included high-speed car chases through the quiet streets of his hometown, Bethel, Connecticut, and culminated in breaking into his neighbor’s house and causing chaos. Despite receiving a relatively lenient punishment of probation, Moore reflects on the shame and embarrassment his mother felt when his name and crime were publicized in the local newspaper.

Having a conversation with Moore, who is currently 65 years old, through Zoom, his relaxed and pensive demeanor gives off an almost scholarly vibe. It is difficult to picture him being so daring and impulsive, considering his upbringing in a respectable and affluent family. I jokingly remark that for a brief period, he embodied the rebellious spirit of punk in more ways than one.

The author reflects on his past and admits that he initially hesitated to include certain aspects in his book, even though his editor advised against it. Looking back, he realizes he was searching for something, but was unsure of what it was. With his father’s passing and his brother in the military, he found himself drawn to a group of rebellious individuals, despite knowing the consequences of their actions.

After reaching the age of retirement, Thurston Moore’s rebellious teenage years are now a thing of the past. He is considered a veteran of American indie rock, although his passion for rock music, as shown in Sonic Life, remains strong. This extensive book consists of 77 chapters and spans almost 500 pages, meticulously recounting Moore’s journey from a small-town music-obsessed teenager in Bethel to the unexpected disbandment of his band, Sonic Youth, in 2011.

“In the beginning, it was approximately four times longer,” he states, referring to the initial draft he turned in to his editor. “It was a massive, unedited collection of material, with countless pages detailing every important record from my punk and post-punk days. Essentially, I just continued writing and included everything in there.”

Sonic Life, even in its simplified version, provides a comprehensive behind-the-scenes look at the American alternative rock scene of the 1970s and 80s. The book includes appearances by notable figures such as Kurt Cobain, Neil Young, William Burroughs, and Iggy Pop, all of whom were either sought out or naturally drawn to Sonic Youth. Despite being formed in 1981, the group remained a noteworthy presence in rock culture for over three decades, though they never quite achieved the mainstream success of bands like REM or Nirvana. Instead, their legacy is based on being arguably the most influential and unconventional rock band of their time. They emerged from the vibrant post-punk No Wave scene in downtown New York in the early 80s and managed to maintain a sense of artistic coolness throughout their career.

Simon Reynolds, the author of Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984, describes how Sonic Youth exuded the effortlessly cool vibe of New York City, reminiscent of the iconic band Velvet Underground. In the early days of their career, downtown Manhattan was still a rough and dangerous area. Even a simple task like going to a diner in the Lower East Side required getting a key from the staff to use the restroom, as they didn’t want drug users in there. Listening to albums like Sister or Daydream Nation by Sonic Youth, one could imagine the band as ethereal beings wandering the Lower East Side in a trance-like state. Some of their songs feel like encounters with disturbed individuals on the streets.

Moore’s memoir vividly describes his beginnings in New York, when he resided in a run-down apartment in Alphabet City. The area was plagued with street crime and drug abuse, causing Moore to sprint to his doorway whenever he approached the corner of Avenue A and 13th Street.

In the past, the current upscale Lower East Side was home to struggling artists and musicians who were attracted to its rough streets due to the availability of affordable apartments and studios, despite the lack of basic amenities. After arriving, Moore finally found the artistic community he had been yearning for since his music-filled teenage years in Bethel, only a short drive away.

The speaker explains that they were naturally attracted to city life. As a teenager, they briefly wanted to live a hippie lifestyle and travel by hitchhiking, but they didn’t enjoy the music associated with it. However, when they were 16 in the early 1970s, they came across a photo of Iggy Pop being held up by people with his body covered in silver paint, and it immediately piqued their interest. They were curious to hear the sound that this image conveyed.

For many years, Moore was closely associated with the independent music scene in New York. However, he has now resided in London for 12 years with his partner, Eva Prinz, who works as a book editor. The couple recently got married and relocated from Stoke Newington in northeast London to a southern area “past Brixton”, although he chooses not to disclose the specific location.

“We’re currently living in the suburbs,” he explains. “I feel more anonymous here compared to living in east London, which I prefer. My wife, Eva, and I are happily married and content with our current situation. However, if someone had told me 30 years ago that I would eventually end up living in London, I would have thought they were insane. But I’ve come to realize that everyone has to find their own place and I’ve grown to enjoy it here.”

Currently, while creating individual albums, going on tour with his band that bears his name, participating in London’s lively and tight-knit free improvisation scene, and managing his own record label, Ecstatic Peace, Moore leads a stable yet connected lifestyle. He admits, somewhat sheepishly, that the only places he regularly visits are record stores and bookstores. Despite being 65 years old, he no longer feels embarrassed about it since he used to hide his love for these activities when he was surrounded by others who were doing more “grownup” things. Now, he embraces it without hesitation.

Unfortunately, Moore will not be actively promoting his memoir. He recently shared on his Instagram that his upcoming book tour in the US has been cancelled due to health issues. He explained that as he approaches his mid-60s, his health has become increasingly debilitating and on the recommendation of his doctor, he will not be traveling until the issue is resolved. The specifics of his condition have not been disclosed.

A

In the book “Sonic Life,” it is evident that Moore’s life was predetermined from a young age. The first chapter, titled “Epiphany,” recounts a moment in the summer of 1963 when Moore was five years old. His older brother, Gene, introduced him to a mysterious single by the Kingsmen called “Louie Louie.” This song, a short and repetitive burst of guitar noise, was a pivotal influence on the American garage band scene of the 1960s and later contributed to the punk sound of the 1970s. Prior to hearing this song, the only music played in the Moore household was his father’s classical records. However, with the introduction of “Louie Louie,” Moore describes a shift in their household’s energy.

The events that followed in his artistic career all stemmed from that one moment. When he was 13, he longed for his older brother’s pristine electric guitar and would secretly strum it with great intensity until the strings eventually broke. By the time he was 16, he owned his own “crazily beautiful sunburst Stratocaster” and was playing along to the music of the Stooges, so enamored by Iggy Pop’s photo on the cover of Raw Power that he brought the album to a local hairdresser and declared, “This is the look I want.” In March 1976, just a few months before his 18th birthday, another significant moment occurred when he saw the Patti Smith Group perform at a nearby venue in Westport. “This was the moment I had been waiting for,” he reflects with excitement, “a true rock and roll transcendence… There was no turning back.”

In 1978, Moore moved to New York and was captivated by the punk scene. He struggled to make ends meet as a musician with his first band, the Coachmen, and used his earnings from odd jobs at art galleries to fund their records, fanzines, and performances. In 1980, he met Kim Gordon, who became his partner in both love and music for the next three decades. The book primarily focuses on their enduring relationship. As a couple, they started making music together and went through various names such as Red Milk and Male Bonding before settling on Sonic Youth. Looking back, this decision was a clear statement of their intentions. When Lee Ranaldo joined as a second guitarist, the group’s distinct sound began to emerge, utilizing unique tunings to create mesmerizing soundscapes for their songs.

Bobby Gillespie, the lead singer of Primal Scream and former drummer for the Scottish indie band Jesus and Mary Chain, reflects on the early music of Sonic Youth. He describes an ominous quality to their songs, such as “Death Valley ’69,” which focused on setting a particular mood and utilizing unique tunings and textures that were innovative and intriguing.

Gordon, who was from California, initially moved to New York to pursue a career in art. She became friends with downtown artists such as Mike Kelley and Dan Graham. Because of her knowledge of the art world and numerous connections, Sonic Youth was able to combine conceptual art concepts and street credibility in a way that had not been seen since the Velvet Underground in the late 1960s. Their initial inspiration came from the underground American hardcore punk scene, and their visual style was influenced by artists like Gerhard Richter, whose painting “Kerze” was featured on their 1988 album “Daydream Nation,” and Raymond Pettibon, whose work appeared on the cover of their 1990 album “Goo.”

I suggested to Moore that their image always had a deliberate and curated aspect, blending both artistic and edgy elements. Moore responds by saying, “When we first joined forces, we had a desire to be everything because we were constantly tuned in and watching. The challenge was how to bring it all together. Our solution was to simply do what we do and see where it takes us. Prior to punk, it didn’t feel like that was possible.”

Moore carefully charts the group’s extensive journey over the span of 30 years and 16 albums, during which they transitioned from being praised by music critics to nearly achieving mainstream success. Their album Daydream Nation is now widely recognized as their best work and a significant influence on the subsequent generation, particularly Nirvana. Along the way, they put out a cover of Madonna’s song “Into the Groove” under the name Ciccone Youth, collaborated with Public Enemy’s Chuck D on the single “Kool Thing,” and received high praise from Neil Young, who invited them to join his tour in 1991. Always a step ahead, they also enlisted the young and unknown Spike Jonze to direct the music video for their song “100%,” and their distinct brand of downtown New York cool remained intact even after signing with major label Geffen Records in 1990.

The book includes biographical sections that offer insight into Moore’s personal life outside of music. These passages touch on his close but complicated friendship with Harold Paris, a flamboyant young gay man who was offended by Moore’s actions when he started spending time with the downtown music and art scene.

According to Moore, Harold may have been fine with the band, but he seemed uncomfortable with the fact that he was no longer part of it. Moore also bought into a persona of being a sarcastic New Yorker, which he now realizes was insincere. Looking back, Moore sees himself in old footage and acknowledges that he would want to punch his past self. However, there was also unreciprocated feelings from Harold towards Moore, although Moore was not ready to openly discuss it due to his own fear of being perceived as heterosexual.

Sometimes, I felt like there was a more personal aspect of his musical journey hidden within this larger, all-encompassing account. When asked about this, he admits, “I could have delved deeper into that aspect. Just Kids, Patti Smith’s memoir, is primarily about her bond with Robert Mapplethorpe. That was the driving force behind her writing it and what makes it stand out, that simple one-on-one relationship. At one point, I did consider shifting my focus to that, but ultimately, people were more interested in the other aspects – the band, the scene – so I included everything and it became a massive project.”

In order to have taken a more personal approach, he would have needed to share the intricate details of the breakdown of his long-term relationship with Gordon. This occurred in 2011 after they had been regarded as the coolest couple in rock for 30 years, 27 of which they were married. The news of their separation caused a wave of disappointment and disbelief within the indie-rock community, where they were highly regarded. Journalist Dorian Lynskey once aptly compared their relationship to that of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward – seemingly solid yet also tumultuous, much like their music.

Gordon expressed her deep hurt and feeling of betrayal in her 2015 memoir, Girl in a Band, while Moore has chosen to stay quiet about the matter. In Sonic Life, he continues to maintain a level of silence, except for mentioning that they went to marriage counseling without success. He focuses instead on his growing relationship with Prinz. When I bring up how their fans saw them as an ideal creative couple, he agrees but seems uneasy.

“I understand to some extent and recognize that there was a lot of public emotion involved in the situation. However, I had no involvement in it and it does not define what happened creatively. When people ask me about this, I often wonder if I know them or why they are so interested in this topic. I had no interest in writing about it and only felt comfortable discussing it with close family and friends. It was a difficult experience, as anyone who has experienced a rift in their relationship can attest to.”

In many ways, Sonic Life is an elegy not just for Sonic Youth, but for lost time when punk and post-punk energised a generation and reverberated through the music that his group and others made in their wake. “Punk was limited but it could not go away,” Moore says, “because no one wanted to see it dissipate. To me it just made it feel like everything was possible.”

The feeling of freedom and sense of belonging that used to be created by underground rock culture seems incredibly far away in today’s world of constant information. Moore agrees but maintains a forever optimistic attitude, sounding youthful. He acknowledges that there has been a change in how we obtain things and that rock music has become commercialized to the point where it no longer shocks, but he believes that there is still amazing music being produced, from experimental jazz and rock to punk. Everyone is participating and exploring, and that will always continue. Nothing is fading away.

Source: theguardian.com