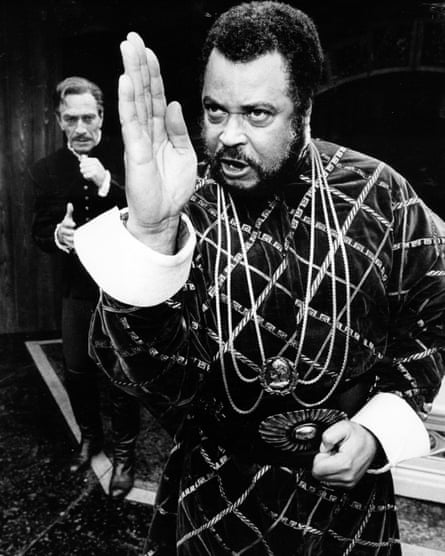

‘His sense of when to be quiet and when to scream to the heavens broke me’

Lenny Henry, actor and writer

James Earl Jones was a towering example of nailing a role until it stayed nailed. The voice of Darth Vader, and of Mufasa. Three times Othello. An iconic King Lear. The Great White Hope, Field of Dreams, his incendiary lead on stage in August Wilson’s Fences. His theme tune should have been Montell Jordan’s This Is How We Do It. James Earl Jones could do it, and how.

Twice, his performances were the high bar I aimed for on stage. When I took on the role of Othello in 2009, I was very aware of the responsibility of playing this brooding Black general who coexisted and performed in an isolated world of white privilege. I wanted to get it right and consulted as many previous versions as possible.

Olivier in blackface was, of course, a key reference – mainly in terms of theatricality and, at times, what not to do. There was Anthony Hopkins’ version, too, and I went back and listened daily to Paul Robeson’s moving, almost glacial performance on a cassette recording of an old LP.

But the main version that rocked my world was James Earl Jones’s. Oh my God. That voice, that gravitas, that passion. His sense of when to be quiet and when to scream to the heavens. It broke me.

I wanted to give a performance like that, but knew that those kind of skills did not just drop into one’s lap. You had to earn it. But I felt that if I aspired to be as good as the big man, perhaps we might get somewhere.

It was the same four years later, when I came to Fences: Jones’s performance as the dangerously frustrated father Troy Maxson was also a high bar to aspire towards. In particular the scene in which his son asks “How come you ain’t never liked me?” and is then given a barrage of reasons in a voice of stentorian thunder: un-tender and entirely humiliating.

Jones’s dynamic and powerful voice quality drives home the idea that being a father does not require a person to like his children. He is responsible for their health and wellbeing and he works hard to provide for them. That is what a father must do. When I saw that performance on video, I was hungry for it and I hope my emulation got somewhere close. James Earl Jones’s wit, alacrity with a text and his imposing size gave him a gravitas on film and on screen.

I worked with him once, on the 1991 Disney comedy True Identity, in which I played a young African American actor who disguises himself as white to escape the mob. My character was given the opportunity to understudy James Earl Jones, who was playing himself – not a stretch; he knew the lines and could improvise all day. He really embraced the experience. I imagine it was good money and working alongside a maestro like him was just effortless. He made it easy. My memory of working with him remains long after the plot of the film has faded.

The last time I saw him was in a kick-ass version of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 2009 in London, where he dazzled us with his portrayal of Big Daddy, the patriarch of the family. Watching him on stage, I felt an ageless, light-footed ease about him. We trusted him as a central character and knew we were in a safe pair of hands throughout.

I was lucky enough to pop backstage after and see him for a few moments. He was gracious and remembered our brief time together on the set of True Identity. He laughed when he saw me and said something like: “How’d that movie work out? The one where you played the white guy for most of the story?” and boomed this massive laugh of appreciation. And then he hugged me. It doesn’t get much better than being hugged by the James Earl Jones. He will be missed.

‘Scaring people seemed to give him a thrill’

Don Warrington, actor

What struck me most about James was his size. He was big physically, big vocally, big in every sense. It was overwhelming. I remember meeting him once: a woman I know invited me round and there he was, sitting having tea. He was charming, with a voice so melodic you could have listened to it for hours. I can’t actually remember what he said, just how he spoke. That theatricality was riveting.

He meant a lot to me, because he seemed to have broken through barriers. He wasn’t tied to his ethnicity, maybe because his father was an actor. So he seemed like a theatrical figure, as opposed to a Black actor. That seemed to have given him a kind of freedom, one that some other Black actors hadn’t found – not due to any fault of their own, but through circumstances.

His success in Star Wars was not a bad thing. Darth Vader, voiced by James, will be remembered for ever. You can talk about all the film’s characters, but this huge figure is the one that really stands out.

We all got frightened by that voice – and still do, even today. He was pretty good at playing bad guys. I think he liked it. Scaring people seemed to give him a thrill. And if it’s something you can do, why not? But I mean in theatre – not in life!

In a sense, he was equivalent to the classic Brit villain. If you look at how Americans regard the British, he had the voice, the stature, the classicism, all the things Hollywood wants villains to have. Sometimes people are very boring in their casting – and he was an obvious fit for generals and presidents. Who knows what he could have done if people had been more imaginative.

Source: theguardian.com