The story of one of Britain’s biggest bands of the past 30 years didn’t begin with rowdy rehearsal rooms or rock’n’roll lore. It started with five school friends in drafty village halls in rural Oxfordshire, paying £1.50 per band member to the keeper of the keys, moving rubber crash mats and plywood chairs to set up their equipment. In barely more than a decade, they were headlining arenas and festivals.

The sweet story of Radiohead’s rise is documented in How to Disappear, a new book by bassist Colin Greenwood, big brother of guitarist Jonny and lifelong friend of singer Thom Yorke, guitarist Ed O’Brien and drummer Phil Selway. Ostensibly a photographic record of their working lives after 2003, when he started taking a camera with him into the studio and on stage, it also includes a beautifully written 10,000-word essay on the experiences they’ve shared.

“The perspective is uniquely my own,” Greenwood writes of his photographs. “I have spent nearly all my working life either on stage or tucked away in a recording studio, where I’ve tried to catch out my friends with my Yashica T4 Super camera, a black analogue plastic box that records light, like our vinyl does sound.” These times are also punctuated by long stretches for which the band members are apart, he adds, which he reflects on tenderly. “When we do reunite, it’s like plunging into the latest season of a long-running box set: everything essentially the same but all of us just that little bit older… coming back together at these moments is both addictive and reassuring – a communion through music.”

I meet Greenwood holed up in the book-lined snug of his publisher, just before he heads off on tour with Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds (as well as contributing to their new album, Wild God, he’s standing in for Bad Seed Martyn Casey, absent on grounds of ill health). A gentle, generous soul, Greenwood is touched when his writing and photography are praised, crediting two “old friends” for making it happen: editor Nicholas Pearson, who encouraged him to put pen to paper, and Charlotte Cotton, one of three saxophonists when the band were starting out in the mid-1980s (when they were called On a Friday), who became a photography curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

“She helped foster and mentor my interest in the early 1990s,” Greenwood explains, sitting in the corner of a sofa. His practice only began a decade later because “everything was so intense” for the band before then. As he struggled to work out how to frame these photographs in his words, he asked Nick Cave – an old hand at writing books – for advice. “And he said, where do these photos begin? You could write about what it felt like then, not to be at the top of your success, but not starting out either. What are you? Where are you going? So I began from there and everything else followed.”

Radiohead’s 1990s had been a whirlwind, as Greenwood goes on to capture powerfully. Signed to EMI after only a handful of gigs, their debut single, 1992’s Creep, was, in his words, a “sugar-rush success”, its video played constantly on MTV, the mixture of longing and rage in its lyrics and sound getting it lumped in, unfairly, with other grunge-era slacker anthems.

Their second album, The Bends, arrived in early 1995, a year that reached summer with Blur and Oasis battling for No 1 and Pulp headlining Glastonbury. Full of strangely beautiful songs about iron lungs, rubber men and fallen skies, it had little in common with the surrounding hubbub of Britpop and took time to take off. “I spoke to so many music writers who’d received The Bends as a promo, left it to gather dust on top of their PC tower, and hadn’t bothered to play it until word of mouth nudged them,” Greenwood writes.

Four singles with powerful videos saw them move up the charts: their last from The Bends, Street Spirit (Fade Out), got to No 5, with a video by Jonathan Glazer (later to direct Under the Skin and The Zone of Interest). Support slots with REM in the UK and Alanis Morissette in the US, and their music being used in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet, also helped. “It meant that when we released OK Computer [in May 1997] nobody wanted to make the mistake of missing out on us again.”

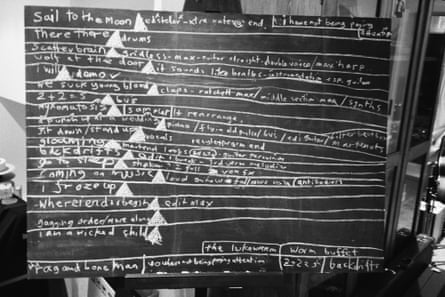

OK Computer went five times platinum in the UK and double platinum in the US, allowing the band to buy and convert a Thameside barn and its outbuildings into a studio. This home-from-home features in this book’s earliest pictures and pops up in the years after that: we see a studio blackboard featuring potential track names from 2003’s Hail to the Thief, and a snap of artist Stanley Donwood, painting that album’s colourful cover in one of its cowsheds.

The tone is private, unpolished, unglamorous. Here is Thom scribbling lyrics, Ed shattered after a night on the tour bus, the whole band wandering on stony sand by the sea. There are plenty of pictures of Jonny, who has never minded his brother’s interventions: pushing a luggage trolley through a silent American airport, looking impish at a mixing desk, playing a viola in a bath to create an interesting sound. He has possibly the world’s most photogenic cheekbones.

This isn’t a tempestuous fraternal relationship, I say – Colin laughs when I mention the Gallaghers. “Well… we’re just very English and very self-contained, really.” Then he speaks with incredible tenderness. “I love working with Jonny, and I love being on stage with him, watching him play and riff furiously.”

Influenced by photographers such as Gaylord Oscar Herron and Tim Barber’s mid-2000s website Tiny Vices, featuring “snaps of small pleasures, photos of friends, road trips documented with 35mm cameras like mine – beautifully curated with an expert eye”, much of the book is charmingly quotidian, but hints of their hugeness trickle through. It’s hard to miss the faded grandeur of the 16th-century manor house on Jane Seymour’s Marlborough estate, their recording space for 2007’s In Rainbows, the many boxes of gig gear backstage, and a lovely shot of Thom singing Spectre – a song commissioned but ultimately rejected for the 2015 Bond theme – in a booth in Air Studios, looking out at an orchestra.

The book ends with shots from mega-gigs in the US, Canada and Ireland after their last album, 2016’s A Moon Shaped Pool. Greenwood takes pictures on stage when his bass isn’t required, and also writes about touring life, enjoying reggae, beer, books and chess with the backline crew, and tea and toast as he sits and stares at the “unending deserts and prairies… feeling gloriously cut adrift until shimmering skyscrapers appeared on the horizon, our next port of call”.

Radiohead last toured together in 2018. Thom and Jonny have made two albums as the Smile with Sons of Kemet drummer Tom Skinner; O’Brien and Selway have solo projects; Colin’s now busy with the Bad Seeds. Where does Radiohead exist now? “We did some rehearsals in, I can’t remember, June or May? Let’s say early June. We just ran through some stuff this summer specifically just to see how it felt and just to reconnect. It was really good.”

He also talks touchingly about Ed’s 2020 debut album, Earth, under the name EOB, and Phil’s “amazing” gig with Portishead’s Adrian Utley a few years ago at the Union Chapel. “Everyone’s been very supportive of one another’s projects,” he says. It’s all terribly grownup behaviour.

Colin’s photographs – delicate, warm, unobtrusive – also feel supportive of his friends, but I wonder what kept him taking photographs all these years. He thinks for a while, then a theory starts to bubble up. “Maybe taking pictures is a way of celebrating and commemorating these moments that are collective – moments that are shared with all these people on stage and all the people off stage, too.”

It’s also made him reflect on the blessings of being in a band all this time – it’ll be 40 years in 2025 – of getting the opportunity to play with them, and the joy of capturing them unawares when they’re about to perform or record. “Or when they’re getting ready or meditating or yawning or doing anything, really.” Greenwood smiles. “They’re still allowing me there when the last thing they want around is an idiot with a camera.”

Source: theguardian.com