Over the past 20 years, Andy Murray has built one of the greatest tennis careers. As he prepares to hang up his racket at the Paris Olympics, those who know him well reflect on the early days of his career and his legacy.

Jamie Murray, Andy’s elder brother and a former doubles No 1 At our tennis club, we were probably the youngest ones that were playing there. We’d always muck in with the older kids. Our mum was the club coach at the time and had a ton of junior players. Not necessarily amazing players, but it was a thriving club. There was a lot of atmosphere about the place and I think that’s where we grew to love the game.

Leon Smith, Murray’s childhood coach and now head of men’s tennis at the LTA I’d first seen him when I was playing junior tournaments and Judy [his mother] would bring him along. He was four or five. I remember him playing short tennis, and he was very highly skilled and coordinated. By 11-12 he was that good. The most obvious thing was that he was playing tennis and football a few times a week, and he took it really seriously, but you put him on a match court and the guy just lit up. He just wouldn’t want to lose. In that Orange Bowl final [an event in Florida Murray won in 1999], I remember him drop-shotting the guy so many times. This guy was much bigger than him – Andy wasn’t that big. He was more average to small size – and he kept drop-shotting this guy because he knew he couldn’t beat him for power.

Jamie Baker, Murray’s longtime friend and junior rival I don’t think I’ve met anyone who was as fast a learner; every time he hit a ball, he was taking something from it, learning from it. Just so in the moment and in touch with the ball and the game of tennis that he was never wasting one second. That’s why, as a junior, his style changed so much. He went through a phase where he would just moonball every single ball. Every single ball. And then the next time you played him, he would be drop-shotting you every single shot. That’s not normal.

Jamie Murray We’re quite close in age but at a young age, I was probably better than him at most things. That changed in tennis quite quickly [he laughs]. I had a brother I wanted to be better than and it pushed us to get better and that desire to want to beat each other, I’m sure, helped us. It wasn’t like in Scotland that we had loads of players, loads of competition and things like that. A lot of that probably came from within our own household.

Ara Harutyunyan, Murray’s roommate and friend at the Sánchez-Casal academy in Barcelona He was a very humble guy, very straightforward. He never had illusions of being a star. His family education and the way he behaved, he had a phenomenal basis for his personality. It’s just that the way people perceive him from childhood up until now – he’s grumpy sometimes, he can walk in a way that people think that he doesn’t want to play or he doesn’t enjoy. But it’s just his physiology. I adored him.

Baker I’m very sceptical of anybody who says they knew Andy was going to be what he turned out to be, when he was 12 or 13. I just don’t know how you could’ve predicted that. The thing about him is that he was always a standout character, he was never somebody in the pack, no matter what he was doing. Whether it was in his tennis or just his general behaviour in life. He was not somebody that would kind of follow. He would always be either doing his own thing, doing something slightly different or behaving in a slightly different way. He was always insanely competitive, abnormally competitive and that was definitely recognisable.

Harutyunyan He was always super competitive and he argued a lot. He wanted everything to be fair. He questioned a lot, like: “Why are you saying this?” “Why?” was his main question all the time. You see that people don’t change, when looking at him on the TV, I saw the same Andy.

Baker His work ethic and his attitude that you would associate with him now actually wasn’t there when he was that age. He was not the person that was by the book, doing all the warm-ups, being the most professional, behaving in the way that players wanted you to behave.

Harutyunyan Every day, each of us were having a jar of Nutella. He was skinny as hell and we were running so much that nothing changed his physiology.

Baker I don’t know when exactly it happened but a switch flicked and he made a decision that this was what he wanted to do. Almost overnight, he became what we know of him now, which is this absolute professional machine, looking at every single aspect of his performance, diet, sleep. All of that stuff that gave him the tools to win two Wimbledons, the US Open and the Olympics. That’s also an equally impressive thing. He wasn’t born with that. That wasn’t how he was behaving as a teenager. He made a conscious choice at some point and the rest is history.

after newsletter promotion

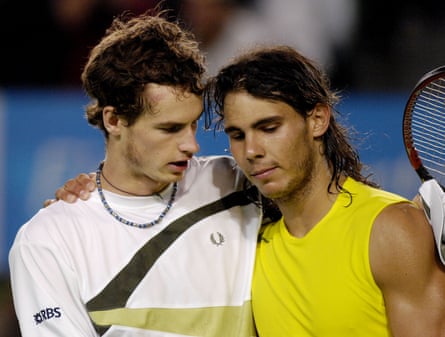

Murray has since won three grand slam titles, – two on home soil at Wimbledon, – and two Olympic gold medals, with a healthy stint at No 1, while battling with three of the greatest players of all time in Novak Djokovic, Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer.

Rafael Nadal, 22-time grand slam champion and Murray’s childhood rival Andy had an amazing career. He had a lot of finals. He was an amazing player that probably played in a difficult moment of the history of tennis because he shared the tour at the prime time of Novak, Roger and myself. He was, in my feeling, the one that was at the same level as us in general terms. In terms of victories, it’s true that he achieved less. In terms of level of tennis, in terms of holding mentally the winning spirit week after week, he was the only one that was very close to being at the same level as us.

Smith You dig deeper than the grand slam titles, you start looking at his tour record and you go: “Yeah, it is a big four.” Slam finals etc. I think that’s what is unbelievably impressive, that he managed to do it. And what I really liked about Andy, he was pretty honest about his assessment of his game: “I don’t have the power or some of the skills that Roger, Rafa, Novak have.” He always accepted that and went about becoming tactically better than everyone else because he maybe doesn’t have that one big serve. Yes, but he works ridiculously hard on his physicality to make him robust enough to play. He made himself robust enough to do what he did in 2016, playing every single week to get to No 1. And played Davis Cup, by the way. And played in the Olympics that year. He made himself pretty much ill that year by doing that, but my god.

Baker Purely, without any of the emotional stuff, he has to go down as one of the greats of the game in terms of achievement. I don’t think the almost invincibility of the other three should diminish in any way what he has achieved. It’s just an incredible, incredible career.

Harutyunyan [His late-career recovery from hip surgery] was a bigger achievement than what he did when he had proper health to play professional tennis. As I understood, this was done to bring his quality of life back, but when he recovered he said: “No, I’m going to play again.” I understand you need a lot of physio, a lot of recovery in order to start running and can you even imagine going through the recovery process? It was very tough to play on the level that he played after the hip surgery. This is the bigger achievement compared to what he did previously. He probably doesn’t think that way, because of the results he had, but it’s truly a remarkable comeback from that type of injury.

Smith First and foremost, he should be remembered as a great champion for us and an amazing role model. Someone who stood up and was vocal about global issues because not many do that. I think he’s prepared to speak about things that are important and people listen to him. You get the sense when the players talk about him, not one person isn’t unbelievably complimentary. People genuinely appreciate what he’s done for the sport and what he’s done for them. He should be remembered for many, many things. A great human being, a great champion, a great ambassador for tennis and wider issues in the world.

Baker Growing up with him, it was actually almost – people use this word all the time – it was almost unbelievable, a genuinely fairytale situation to think that this eight-year-old kid would actually one day win Wimbledon.

Source: theguardian.com