What is the Shakespeare canon if not the ideal treasure trove of IP? Truancy laws mandate that students develop at the very least a passing familiarity with Romeo and Juliet, the highest-brow pop culture artifact nonetheless considered universally common knowledge, and the themes isolated in those lesson plans can be easily mapped onto present-day scenarios: the heedless forbidden passions of Romeo and Juliet, the topsy-turvy crushes of Twelfth Night, the power struggles of Hamlet, Macbeth, and Lear. Best of all, as far as Hollywood types are concerned, it’s all open-source mythology in the public domain, the sweet spot of brand recognition nobody has to pay for.

And yet since the decline of the studio system’s golden age, there hasn’t been much of an effort to make uppermost-tier blockbusters out of the stories themselves, the closest thing being Justin Kurzel’s distinctly post-Game of Thrones take on Macbeth. (Even that was treated as a niche-market British import as it underperformed at the US box office.) With the marked exception of dyed-in-the-wool classicist Kenneth Branagh, a man who spent many years under the impression he was put on this Earth to succeed Laurence Olivier until his prompt pivot to franchise hackdom, most artists consider it unsporting to take the Bard so literally. Some level of engagement – whether a superficial reskinning of plot points or a deeper revision of tone, structure, and significance – is needed to answer the question “why bother?”, fairly asked of texts done to death over several centuries. The obligation to revitalize has aged past artistic tradition to ossify into cliché, succinctly skewered in the Onion headline Unconventional Director Sets Shakespeare Play In Time, Place Shakespeare Intended.

The selections gathered for the Criterion Channel’s new streaming collection Pop Shakespeare cast a wide net, from 1979 to 2012, and from faithful transplanting of the original verse to top-to-bottom remixes. They’re all united, however, in their earnest effort to find a meaningfully novel angle on the well-trod that surpasses mere aesthetic update to unlock fresh perspectives on the past, the present and the distance between them. While a lot of the fan-favorites that might first spring to mind have been omitted – there’s no shortage of places on the Internet where one can watch 10 Things I Hate About You – the eight curated titles share an iconoclastic streak motivating big-swing risks in their critiques of and homages to the playwright’s genius. The queer punk visionary Derek Jarman, for one, never met an emblem of English patrimony he couldn’t defile, and his 1979 reimagining of The Tempest “cut out the boring bits”, as star Toyah Willcox put it. He only had reverence for the theatre itself, metaphorically piling 350 years of productions on top of each other with grab-bag all-eras costuming and other free-floating anachronisms.

Compare and contrast Jarman’s conceptual experimentation with Paul Mazursky’s approach to the same play three years later: the plainly titled Tempest, refashioned as a present-day domestic drama stretching from New York to Athens with grand-champion sparring partners John Cassavetes and Gena Rowlands as the embattled central couple. Roger Ebert found the film insufficiently transformative in his thumbs-down review (“Mazursky hasn’t absorbed ‘The Tempest’ in his ‘Tempest’; he has simply staged it”), but converting the dynamic between Prospero and Antonio from brothers to lovers tilts the text on its axis, as does the addition of a carnal element to Ariel’s servitude, all these jealousies and intimacies made stronger and more pointed. In any case, to a modern audience, the primary appeal comes from casting that includes a 14-year-old pre-fame Molly Ringwald and a sexual-prime Susan Sarandon visibly gearing up for the aloof horniness of The Hunger.

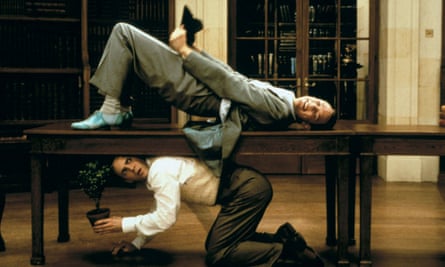

Criterion’s promo copy plays up the same fundamental draw for this fare as your given season of Shakespeare in the Park, the viewing public mainly enticed by the chance to see their favorite actor flex their technique-muscles and have a bit of fun. (Or, as in the instance of Baz Luhrmann’s supercharged teenage dream Romeo + Juliet, to gawp at two preternaturally pretty people with volcanic chemistry.) That’s the best pitch for 2012’s Much Ado About Nothing, directed by Joss Whedon during a contractual two-week break from post-production on The Avengers, shot in his own home with an ensemble of his most available repertory players. Between the unsightly monochrome digital cinematography and several self-satisfied, overly demonstrative performances, there’s little here for non-Whedonites, but the casually thrown-together atmosphere nonetheless gets at the essential truth that a big, important part of theatre is goofing around with your friends.

Much Ado has trace amounts of what could be called Shakespeare Acting, but Branagh’s interpretation of Love’s Labour’s Lost practically supplies a definition; either out of worry that today’s groundlings are too stupid for comprehension or too inattentive to stay tuned, the cast overplays each line to within an inch of its life, most egregiously in the all-caps comedy announcing the jokes as they come. And ’tis a pity, for the Luhrmann-esque style clashes with Branagh’s inspired tributes to the Fred Astaire musicals of yore, scrupulously recreated in bright-n-sprightly song and dance numbers taking the place of expository dialogue. For its handful of shortcomings – most notable among them a whiplash pivot into a more somber tone as the second world war descends upon our lovers and fools – there’s still some measure of innate likability in Branagh’s unbridled enthusiasm for the oldies that never stopped being goodies.

His flawed nostalgia play complements the finest cuts from Criterion’s sampler, all of which use Shakespeare’s soundly constructed tragic frameworks to look forward and beyond. Abel Ferrara’s grubby, gorgeous China Girl relocates the Montagues to Manhattan’s Little Italy and the Capulets to Chinatown, their turf war exacerbated by a city forever encroaching on its last remaining pockets of authentic culture. With 2000’s Hamlet, Michael Almereyda sweats the technological anxieties pervasive circa Y2K, in particular the matter of where all this progress leaves cinema; closed-circuit video monitors form a flat, cold hall of mirrors, and Ethan Hawke’s shiftless prince delivers the existentially tormented “To be or not to be” monologue while wandering a Blockbuster. Personal, expressive, subversive, and insightful about its source, My Own Private Idaho supplies the most teachable exemplar of creative adaptation in condensing the Henriad to the saga of two street hustlers on parting trajectories. In shifting Keanu Reeves’ Prince Hal stand-in to a supporting role as sidekick to his own sidekick, Gus Van Sant coaxes out unseen nuance from the text, imbuing it with newfound passion, world-weariness and vulnerability.

The mournful final note sees River Phoenix’s queer icon Mike Waters picked up by a stranger while passed out on the side of the road, reclaimed by the only home he’s ever known. There’s an unmistakable melancholy in his return to destitution, but he peacefully slumbers through the beginning of his next time around an eternal cycle. Ultimately, this is also how writing stands the test of time – through endless regeneration and reincarnation, torn down and made immortal in the process.

Source: theguardian.com