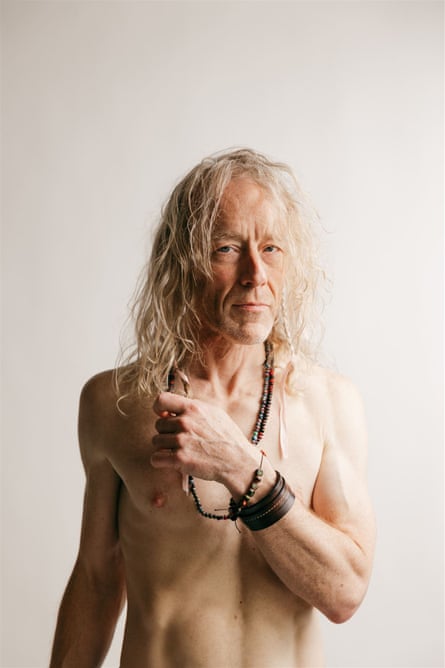

‘One of my deepest hopes is that Mimi can continue to be the light …” Alan Sparhawk pulls his arms up tight around his head, covering his face and entangling his fingers in his long, curly hair. They stay there as he gathers himself, as he tries to staunch, or at least disguise, his distress. As much as he struggles, however, the tears are winning.

We are talking about his new music, but Sparhawk’s previous life casts a long shadow. In November 2022, his wife, Mimi Parker – his bandmate in the indie band Low since 1993 – died of cancer at 55. The grief Sparhawk feels is still raw, still overwhelming. He composes himself and continues: “Many people expressed real love and grief over her, but I felt a lot of things that nobody could touch, things that left me feeling very alone. I hope Mimi can be the light and something that people draw strength from.”

We are four minutes into our interview and I’m wondering if I should suggest reconvening on another day. On the other end of the video call, at home in Duluth, Minnesota, Sparhawk is still wrestling with his arms, his voice cracking. He won’t be able to talk his way out of Parker’s absence, but I am hoping he can talk his way through it. I know he can.

In January 2020, my wife, Jacqui, died of cancer at 56. We had been a couple for 35 years; Sparhawk and Parker were together more than 40. “If you fall in love, you know that could happen,” he says, taking his time over every word. “That person is so real and then they’re gone. For me, that shook the foundations. I’m still trying to figure out what Mimi’s death means, to see if there’s anything else I don’t know.”

Sparhawk and Parker met as preteens; they were inseparable before they left school. They had two children and made 13 albums, scheduling their tours around schooling. Sparhawk had mental health and substance issues, but the couple endured them, Parker stoic behind her drums, carrying the air of someone who understood life and would remain unbowed. Low never sold out arenas, but they had a loyal and growing fanbase who felt the couple’s love. After spending almost 30 years making music, the band (a trio, featuring various bassists over the years) seemed as vital and forward-looking as ever.

White Roses, My God is Sparhawk’s first album since Parker’s death, and it may not be what fans of Low expect. There are no traces of the band’s glacial early years, with their exploration of the power inherent in dramatic shifts from quiet to loud, nor of the subversively catchy tunes of their middle years. The gaps between the two harmonising voices on those songs – Just Make It Stop, What Part of Me, Try to Sleep – is where sadness alchemised into a kind of light.

Instead, there are nods towards the final two albums the band released – 2018’s Double Negative and Hey What, issued in 2021, after Parker’s cancer was diagnosed – when layers of distortion transformed sets of seemingly straightforward songs into undeniably challenging material. Sparhawk has gone yet further with that strategy, using synthesisers, drum machines and dance beats and pitch-shifting his voice beyond all recognition.

“The tools I used before no longer work,” he says. “I’m trying to use my voice, but I don’t want to hear my voice, so I needed to find another voice.” He stops, wondering if he is making sense. “It felt like I was stabbing into the unknown, trying to figure things out. I started the machines, messed with them until something resonant happened, and then I started singing. And, sometimes, something would come out that I could not stop and I could not mess with.”

There are records that reverberate with grief. When Nick Cave’s Ghosteen was released in late 2019, listeners were primed to seek echoes of the death of his teenage son Arthur. It felt as if Cave was reaching out to a community bonded in grief. Sparhawk agrees. “A grieving record, yet still resonant, beautiful and so eloquent. I can’t decipher the world that way; I’m not that kind of writer.” The title White Roses, My God instead points in multiple directions, with the flowers symbolising eternal loyalty and new beginnings.

Among the influences were Prince’s pitchshifted alter ego Camille and Neil Young’s Trans, on which he used similar vocal effects to communicate with his son Ben, who has cerebral palsy. Yet it’s hard not to be reminded of Cher’s Believe. “You’re right!” Sparhawk yells, excitedly. “There’s an ecstasy to that song that I sometimes felt.” He then blends Cher’s lyrics into his, mashing Believe with Feel Something, the most obviously future-facing song on White Roses, My God. “Do you believe in life after love? I think I want to feel something … Do you believe in life after love? Can you feel something here? It’s the same. I’m trying to celebrate, I’m trying to believe.”

Isn’t that the key, I wonder: we have to believe in order to carry on, we have to develop as the person they loved to celebrate them? “Yeah, then you’ll be the right person for her, the person that you are, and you’ll make Jacqui proud.”

Really? I get the feeling she is mostly disappointed with me, a little bit angry and a tiny bit proud. I’ll take that. He laughs. “It sounds like you had the same dynamic. Mim is a little bit disappointed, watching, ensuring I don’t go off the cliff. They gave us the freedom to be who we were and we became who they wanted us to be. And that’s a really beautiful thing. Sometimes, someone who needs guidance finds the person who is OK with saying: ‘I see who you are and that’s why I love and trust you.’ That was the dynamic with Mim. I’m just an engine; she steered.”

Even without his wife’s guidance, Sparhawk has kept busy creating music since 2022. Encouraged by Lambchop’s Kurt Wagner – “a friendly hand reaching out to say: ‘Hey, I know you’re in the middle of a process, but we have some shows …’” – he began gigging again. He played music with his daughter, Hollis, and formed Derecho Rhythm Section, a punk-funk outfit, and Damien, making funky electronic experiments with his son, Cyrus. “I’d been playing a little bit with Hollis and Cyrus at home and music had been continuing, especially through my son,” he says. “It felt like music was still there, you know, and I was even able to write songs, surprisingly, that seem to feel like they’ve come out of this experience, or at least from a certain stage of it.”

He is also finishing off a second solo album, this time in collaboration with fellow Duluthians Trampled By Turtles. “It’s kind of the opposite, acoustic, but I didn’t set out to go in that direction. These are just things I did with friends.”

When we emerge from that initial phase of grief and shock, friends can give us permission to be who we were again, I say. “I can look back at multiple incidents and, yeah, everybody was trying to extend their love,” says Sparhawk. “Some friends simply said: ‘Why don’t you come hang out with us for a while?’ Others invited me to California to sit in the sun for a couple of days.”

Would Sparhawk ever play Low’s songs again? There is a pause as he reflects. “So far, it feels most appropriate to be doing new things. I was always trying to push forward, finding a new challenge. Maybe down the line there might be the right moment, but it feels like Low is still very sacred. For now, I will just have to trust what’s coming out of me, because that’s what I’ve always done.”

Faith, belief and trust – the latter a title of a Low album from 2002 – loom large in his life. In November 2022, Parker’s illness caused Low to cancel a headlining slot at Le Guess Who festival in Utrecht; she died the week before the festival. Sparhawk, billed as a solo artist, accepted a return invitation 12 months later. I was there, impressed by his fortitude, yet concerned it could be too soon for him. “I didn’t consciously decide I needed to get back on the road,” he says. “It was more: hey, this is what you do.”

Midway through the show, Sparhawk’s emotions appeared to boil over, as he hurled unrestrained rage at the high ceiling of the 13th-century Jacobikerk. Songs such as Don’t Take Your Light Out of Me and Screaming burned with self-evident agonies; JCMF (Jesus Christ Mother Fucker) seethed with fury at the unfairness this lifelong Mormon had had thrust into his world. None of these songs are on the new album, however. “I had a handful of songs that I’d written while things were going on, a few old songs that I’ve never recorded that, for some reason, felt right to play at that point, plus a few songs that I was starting to work on that, essentially, became this record,” says Sparhawk.

How does Sparhawk reconcile with his faith today? “It was very much a strength when Mim was passing,” he says. “Since she died … I don’t know that I’m angry at God, or disappointed, or disillusioned. I am surprised. Maybe this is a test, or maybe it’s just the way it is. With grieving, you lose your sense of spirituality and your sense of the universe and they take time to return.

“I’m having to accept the possibility that maybe the universe is different from what I thought, from what I was taught about our spirits being eternal. Maybe there is nothing – and this has been the first time I’ve had to look at that possibility. But just in the past couple of months … I’m starting to believe again that there’s an eternal nature to our beings, that we somehow are more connected with magic and mysticism in the universe than we realise.”

Given he believes his spirit may yet spend eternity with hers, I ask what his relationship with Parker is like today. I can feel Jacqui walking alongside me and even sitting on my shoulder; I talk to her every night before bed.

Sparhawk looks a little alarmed: “How soon were you able to do that?”

I wonder if I have gone too far into a private realm; Sparhawk takes time to process his next response. “It’s only recently that I’ve been able to see Mimi’s face. I’ve been seeing her hand in things, seeing her sense of humour and her joy. In the beginning, I really had a hard time feeling her there. I thought I would feel something and I was shocked that I didn’t. A friend of ours sent me a letter, in which they said they felt they had received a message from Mim. I read the message and … it was so alive. I’m not sure how much I believe that stuff, but I have to trust my feelings.”

Sparhawk perks up considerably, as if he has just had a revelation. “There are things going on in life right now that she’s really happy about. I think part of her message is: ‘I’m sorry this took so long.’ Sometimes you have to go through the process, and this is just the beginning. You say you can feel Jacqui beside you, and now I feel Mim’s hand on my shoulder or even like this,” he says, putting his hand on the back of his head.

Messages are a strange phenomenon, I suggest. Sometimes I’ll find something Jacqui wrote and it resonates. Often, I’ll hear a song she didn’t know and imagine she is speaking to me through it – Tracey Thorn’s Dancefloor, for example, which portrays a woman looking back on adventures she had in her youth. Thorn has the wisdom to – that word again – celebrate them and wish they had never ended: “Where I want to be is on a dancefloor / With my friends all beside me …” Now, Sparhawk has recorded an album where I hear the same impulse. So, is he a dancer?

“Yeah, but it’s very primal for me, and very childlike, so I’m private about it.” He is beaming now. This is how grief works: you remember and you smile and laugh. Happiness may be out of reach, but contentment is attainable. Then something triggers you – a song, a picture, a smell – and emotions spill out. You lean into the tears because you know they have to win. But would you want to stop crying, or missing the love of your life? Don’t you want to feel something? Do you believe in life after love?

“If you can get your body to let go, you’ve let your mind go,” he concludes. “It’s the ultimate stage of surrender. Dancing doesn’t solve everything, but it acknowledges: ‘Yes, well, here we are.’ I don’t know what the truth is, but I know that if you keep dancing you’re going to get a lot closer to it.”

Source: theguardian.com