All documentaries celebrating artistic geniuses face the challenge of how to recognise their talent without coming across as pure puffery. The dynamic is different in the rare event that the film-maker is personally related to the subject, as is the case in Revealed: Otto by Otto – a portrait of the great Australian actor Barry Otto directed by his daughter Gracie. She flips a potential downside – being so close to the person documented – into a virtue by crafting an emotionally rich film that truly could not have been made by anybody else. It is filled, like Otto’s performances, with light and shade.

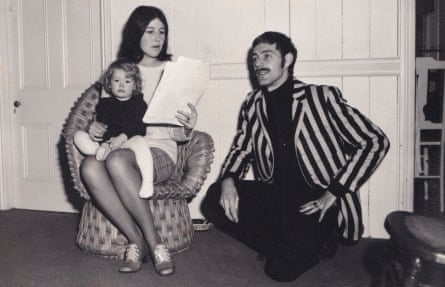

Otto by Otto (which premiered at this year’s Sydney film festival and arrives on Stan on 16 June) begins unassumingly, with grainy home videos and footage of the now-retired actor hanging out with his cats in his cluttered Petersham home among books, paintings and curios. Gracie takes her father to Brisbane to retrace and discuss aspects of his childhood, growing up in a poor home, eating tripe obtained by his abattoir worker father. This leads into his early stage career, relocation to Sydney and his cinematic work, starring or co-starring in several classic Australian films including Bliss, Strictly Ballroom and Cosi.

Due to the ephemeral nature of theatre, Otto’s film performances are the ones people return to year after year, despite not necessarily being his best. If movies are moments sculpted in time, to paraphrase Russian auteur Andrei Tarkovsky, theatre cannot be bottled or stored. It instantly vaporises, living on only in the memories of the audience (even when recorded by a camera, which cannot capture the magic of live performance). Otto starred in many plays throughout the 70s, 80s and 90s, including some held in the now defunct Nimrod Theatre, which, as the film recounts, disbanded and reformed as the Belvoir St Theatre.

We see clips of the subject performing in stage productions, including Welcome the Bright World, Cosi and The Tempest, starring in the latter alongside Cate Blanchett. Her recollections, like other interviewees, are heard but not seen, their commentary laced over archival footage – a strategy that works well to keep the film visually focused. Others include Baz Luhrmann and Ray Lawrence, who directed Otto in Bliss, a film where he brings an indescribably strange magnetism to the sad sack protagonist: a middle-aged madman who drops dead from a heart attack then finds himself in a bizarro half-reality or kind-of hell, where his wife has sex with his business partner in plain view and his children share an incestuous relationship.

Initially, Otto by Otto feels a tad stock standard but the film evolves into something quite special and distinguished, making a melancholic point, never directly spoken, that not even the greatest storytellers can control the narratives of their own lives. One chapter details how Otto was working on a highly anticipated one-man show, The Kreutzer Sonata, in 2013, which ended very sadly: after completing two preview performances he had a nervous breakdown and pulled out. “We tried to talk him round but he couldn’t do it,” recounts his wife, Sue Hill, adding that afterwards, “his depression really ramped up”, he “withdrew inside himself” and “it just broke him”.

Otto was later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, which Gracie doesn’t mention at the outset, reasoning perhaps that doing so might emphasise this aspect of his story over others. It’s a delicate balancing act: to reflect the essence of somebody’s character, their personhood and self, incorporating such things as life-changing illnesses and diagnoses without suggesting they’re defined or necessarily limited by them. Another point never spoken: this is the kind of film the Otto of old would surely have wanted made about him – rich with nuance and unafraid to acknowledge life’s many troubles and troughs.

Ultimately it’s inspiring: a very memorable documentary about a one-of-a-kind talent who has long danced to his own beat – in one instance almost literally. The film contains vision of a surreal moment from Strictly Ballroom in which Otto – playing Doug Hastings, the father of Paul Mercurio’s protagonist – dances by himself in front of a blackened tableau, moving and swaying to some sad and beautiful rhythm, as the actor himself has done in so many ways over so many years.

Source: theguardian.com