‘He stood in the middle of the party wearing a gas mask’

Keira Knightley, co-star in Pride and Prejudice (2005)

Donald was a giant. When you meet most actors, they’re surprisingly small. But Donald was huge. I remember feeling unbelievably intimidated by his size and reputation when I first met him. He had this clause in his contract that no one was allowed to smoke anywhere near him. Most of the rest of the cast were in their late teens and early 20s, all chugging away.

We used to manically wash our hands and spray ourselves with perfume after, so he wouldn’t know. He’d sniff the air as soon as he came on set and we’d all nervously shuffle about. At some point during filming, he came to a party we all had in a gas mask so we could all smoke. I will always remember him standing in the middle of that party in a gas mask.

He was terrifying and impish and generous. He gave us all gifts and invitations to visit him on his lake in Canada. I wish I’d gone. He was full of stories and mischief. Strange and wonderful and loved by all of us. He will be greatly missed.

‘He was hurt to have never been nominated for an Oscar’

James Gray, director, Ad Astra (2019)

It’s impossible to talk about Donald without acknowledging his perfect timing. That such a person could become a movie star is a testament to what a wonderfully fertile time the mid-60s and 70s were for the cinema. He could have only happened in that moment. Donald was a true contradiction, a rare talent. He could convey great presence and tragic awkwardness at the same time. His genius was his ability to lay bare a wounded soul at war with himself. Unlike the superheroes with whom we are now obsessed, he played heroes: tremendously complex figures whose lapses allowed for transcendence and beauty.

I think the ending of Fellini’s Casanova – in which his character is dancing with the doll – is one of the most moving things I’ve ever seen, mostly because of his tragic and anguished vulnerability. In Klute, his character solves the crime, but what moves us is his self-loathing and tenderness.

It’s very hard to act an emotionally repressed character – a performer without a lot of moments of explosive and declarative scenes necessarily must rely on the depth and quality of his thoughts. In fact, our celebrations of great performances often involve ones with a lot of yelling, but Donald allowed the richness of his inner life to speak for itself, and his work looms large.

In that way he’s a beautiful symbol – maybe even the apotheosis – of the 70s actor. What we love and remember most about those movies might well be their conflicted leading characters: Al Pacino in The Godfather, struggling so deeply with profound moral and ethical conundrums. Robert De Niro in Raging Bull. Gena Rowlands in A Woman Under the Influence – a person ever in turmoil. Donald’s work was all about a mature confrontation with our internal schisms, and he seemed utterly unconcerned with “likability”. His haunted face conveyed a deep well of sadness and longing.

But he wasn’t like that in person. In fact, he was quite joyous. I wrote Donald’s part in Ad Astra with him in mind, and made a lot of adjustments to the shooting schedule to accommodate him. During the shoot, we became very close. He was the perfect combination: an actor who comes with ideas but also understands that it’s a dictatorship, not a democracy. He really revered directors he respected, and his choices always surprised and excited me. He had tremendous energy and would always put up a fight for things he cared about. I almost always let him win because his arguments were better than mine.

Donald was very aware of how cameras would respond to his physicality and how various lenses would treat his face. He was also one of the great listeners of all time, and that would always inform his reaction in a scene. Over multiple takes he’d give you beautifully different things. And then, if you gave him an adjustment, he’d be great in a whole new way: the sign of an extremely trained and accomplished actor.

On set, I like to play a lot of classical music and Donald always knew the piece, no matter how obscure. Even, once, some early electronica by Éliane Radigue – a drone, lasting several minutes. He knew it right away somehow.

So we really vibed. After the shoot, we talked with some degree of frequency until he got sick. He liked to discuss history, art, politics, literature. During the early lockdowns, I called him up and said I wanted to finally get round to Goethe’s Elective Affinities, which of course he had read. So as I was reading it, I had a sort of personal book club with Donald Sutherland. It was fantastic.

He was extremely learned and had an informed opinion on virtually everything. He reminded me of the German actor Maximilian Schell – the two had very similar dispositions; they shared a kind of resigned wisdom.

Donald was aware he’d made his mark as an actor. But I know he was deeply hurt that the Oscars never thought to nominate him for anything. I would tell him how silly it all was, but it had made him feel not fully part of the community. Who knows, maybe it made the work richer.

He was also very conscious of the degradation of cinema. Most artists who lived through the 60s and 70s are now in a kind of extended feeling of mourning – not just for the people who created some of that beautiful work, but for a system that no longer accommodates it and for the cultural guardians who no longer seem to want it.

Donald knew he wasn’t a movie star by business decision but rather due to the caprice of history – and he played a significant role in a mature culture willing to embrace complexities. I’m not sure he’d be a star today. So much of bad art is about the external fight without any acknowledgement that we are all haunted by our riven souls. We oversimplify ideas of identity and look at the world with a very black-and-white, Manichean approach.

Donald was not that. On screen, Donald was fucked-up. But fucked-up is the core of drama. And Donald was its heart.

As told to Catherine Shoard

‘We had such a deep, sublime chemistry’

Elliott Gould, co-star, M*A*S*H (1970), Little Murders (1971) and S*P*Y*S (1974)

Donald was the best partner in movies I ever had. We were brothers and we loved each other. We had such a deep, sublime chemistry. There was nothing intellectual about it, just this amazing natural harmony. I first met him in the commissary at 20th Century Fox when Robert Altman told us to have lunch together after I’d been cast in M*A*S*H. At first I thought: I don’t think this guy likes me. But it was just the opposite. The thing was: we were such opposites. I’m a Jew from Brooklyn and he was a Canadian from Nova Scotia. But it was perfection: never any conflict, just bread and butter – a relationship that felt like a miracle.

Making M*A*S*H made us immediately close because while everyone else was working with Bob Altman, we worked for Bob Altman. He kept us a little segregated. We were both really unsure about the improvisation, the direction of the movie and Bob’s approach in general.

Donald was hired well before me, but once I signed on we had the same deal: no less than second billing, and the same money. Later in production, Richard Zanuck, who was at that time running 20th Century Fox, said they wanted to give me first billing. I thought: “Oh that’s a nice honour. But Donald is my friend! I’m not going to be opportunistic – he was here first and should have first billing and I’ll stay in second place.” That’s what Donald meant to me. I never told him about that.

A few years later, I turned down the screenplay for the movie that became S*P*Y*S, about two bumbling CIA agents. Then Donald called and said: “Would you do it with me?” And I said: “Oh that’s a different story. Of course!” On the first day of shooting in London, we drove to work together and he said: “What do you think of the script?” I rolled the window down, threw it out and said: “It’s a piece of junk. The only way this will work is if we swap parts.” But the producers could not digest that, so we just did the picture. Yet we did bring some of our own ideas to the table. There wasn’t an ending, for instance – so Donald and I agreed that we would just walk up the road with our backs to the camera and sing Side By Side.

We worked together and we succeeded together, but we didn’t socialise very much – though having the opportunity to develop a relationship with some of his family was a total joy. Once, Donald was making a movie in the Bahamas and I came to visit because I had a week off from making The Long Goodbye and was interested in his leading lady, Jennifer O’Neill. Kiefer, his son, was five or six and Donald introduced us. Kiefer wanted me to stay, so when I said goodbye, I said: “Kiss me, Kiefer.” He had an ice cream cone in his hand and put it on my face – he kissed me with his cone.

Donald was a true human being – and not all of us are. He could identify with any of us. His presence and his nature, his life and his mind are an asset for everyone. We all come and go physically, but as a being, he was really special and unique.

I don’t put anything in the past. With me, it’s all in the present. My feeling is that for as long as I am living, Donald will be with me. I have no doubt about that, and I’m not being sentimental. I can see Donald now. I will see Donald for ever. CS

‘He’d get sick with nerves before the first day’s shoot – even after making 120 films’

Francis Lawrence, director of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013), The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 (2014) and The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2 (2015)

I first met Donald in 2012, when I’d signed on to direct the second Hunger Games film. He wanted to meet on 4 July – a public holiday in the US, which I thought was strange. He chose a steakhouse at 9am, which I thought was stranger. I was intimidated because he had such gravitas. I remember he came into the Pacific Dining Car restaurant, sat down and instantly became conspiratorial: if I ever met his wife, he said, I was not to tell her we’d had giant New York steaks for breakfast, because he wasn’t supposed to eat them any more. That totally disarmed me and I instantly fell in love with him.

When we were on set, he’d call me “Governor” and sometimes hold on to me as we walked along. One day he seemed sad and I asked him why. He said: “Because this is almost over.” I was like: “No! We still have a few days and it’s not even the last movie.”

That evening, he wrote me this hilarious email blaming his sadness on a handful of bad grapes he’d eaten. As soon as he got back to his trailer after our walk, he wrote, he’d blown a hole in the lavatory. Now they’d need to burn down the trailer and he hoped that didn’t disrupt the shoot. It was great fun and it was written really beautifully. Now I’ll have to frame that email.

Donald was very politically engaged and that’s why he wanted to do The Hunger Games. He loved that we were smuggling these ideas about the consequences of war into a pop cultural phenomenon. He certainly didn’t give a shit about being a celebrity. It was all about the work and craft and collaborators.

A lot of people see the character he played, President Snow, as the villainous antagonist of those films. And he is – but we needed to find out what his belief system was. Snow believed in the Hobbesian idea that everybody in this world is savage and therefore needs to be ruled with an iron fist. So Donald and I talked a lot about that, on a core thematic level.

He was surprisingly fragile and vulnerable. He’d get very nervous – sick, even – before the first day of shooting, despite having made 120 movies. And yet he seemed so relaxed on screen. Anyone who rises to his level has a kind of magical charisma that’s hard to pinpoint. And Donald was full of complexities: a man of immense power, intelligence and dignity who also had a childish irreverence and a wicked sense of humour. He was very easy to love. But I certainly wouldn’t have wanted to be on his bad side. I think those contradictions are what made him so interesting. A lot of people don’t have any of those attributes. He had all of them. CS

‘I remember that bear hug and its warmth’

Ralph Fiennes, co-star in Land of the Blind (2006)

I worked with Donald on a little-seen film called Land of the Blind, set in a dystopian, futuristic, slightly Orwellian world. He played a leftwing revolutionary imprisoned by a rightwing regime. I played the prison officer who helped to release him and witness him become, in turn, an autocratic and ruthless dictator.

The first time I met Donald was before a rehearsal on set. My father had just died and I suppose someone must have told Donald because as I walked towards him he put both his arms out and enveloped me in a huge bear hug. That said everything. I remember the warmth of it very strongly.

What impressed me about him was his hunger, his enjoyment of acting and his love of discovering the scene. He had a benignly competitive quality – he wanted to challenge you with his performance in the best sense. He wanted to go toe-to-toe with you but with a frisky relish of sharing the scene.

He was full of wonderful jokes, dirty jokes, irreverent jokes. He had a fantastic twinkle in his eye, a mischievous twinkle. He couldn’t bear smoking and I know he had strict rules about not being within so many metres of anyone who smoked. Like a lot of actors of a certain age (he must have been in his late 60s at that time), he had very precise requirements about the conditions in which he would work.

He was alive with a delight for acting, with a wonderful thirst to refine a moment, refine a shot. I remember his generosity of spirit and I’m only sad I didn’t have the opportunity to work with him again. What a loss it is. What a great actor.

‘He learned the name of every crew member. What a gent’

Kevin Macdonald, director, The Eagle (2011)

Tall and imposing, with those distinctive hooded blue eyes and a hawkish profile, Donald was quite scary on first meeting. Ridiculously well read in history and literature, with that distinctive accent poised between patrician and farm boy, he gave off a “don’t suffer fools” vibe. But it didn’t take me long to realise that the forbidding exterior hid a kind, sensitive, sometimes insecure and endlessly curious man. An utterly distinctive life force.

He was already well into his 70s when I worked with him, and his schedule was extraordinary. He was flying around the word doing cameos and supporting parts at a rate that was exhausting to behold. Being a star didn’t interest him any more. He just loved to act.

As a director, one worries that an actor like that is going to turn up and just phone it in. But that wasn’t Donald. He would be on set before anyone else and stay there all day no matter what time his call. He learned the name of every member of the shooting crew and on his final day he personally distributed a thank you card to everyone. What a gent.

He sent me endless notes fretting over upcoming scenes, written in his distinctive ink-pen scrawl. When I commented on them, he ordered me a giant box of the disposable ink pens he favoured. I still use them and think of him when I do.

For a man who on the surface felt like the ultimate pro, he was touchingly nervous and a little superstitious about his performance. His only non-negotiable demand was that we shoot his first two appearances in the film late on in the schedule, once he had found his way into the character. “You only have one chance to show the audience who this character is,” he said, “and I don’t want to fuck it up.”

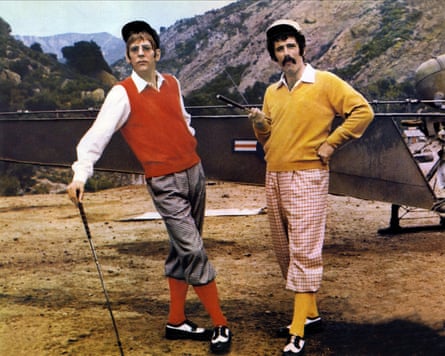

We went out for dinner a few times and he never seemed to resent my endless nosy questions about his oeuvre and the array of brilliant directors he had worked with: Roeg, Fellini, Aldrich, Pakula, Sturges. I mean the list goes on and on. He even indulged my childhood passion for Kelly’s Heroes, in which he played Oddball, a crazy, proto-hippy second world war tank commander, merrily telling stories of the mayhem he caused driving around drunk in his tank in a little village in Yugoslavia.

At the last dinner we had together, before he flew home to his farm in Canada, Donald gave me a copy of John Maynard Keynes’s seminal analysis – and evisceration – of the Versailles treaty and told me it would make a great film and he wanted to play Clemenceau. It’s a great regret that I didn’t take him up on it.

Source: theguardian.com