Nearly six years after it was engulfed by a devastating fire that inflicted incalculable damage on Brazil’s cultural heritage, the country’s national museum has received an important donation of more than a thousand fossils as part of a campaign to help rebuild the collection lost to the flames.

The fire, caused by an electrical short-circuit on the night of 2 September 2018, consumed the former imperial palace which housed the 200-year-old museum in a park just north of Rio de Janeiro’s city centre and destroyed about 85% of its archive of 20m artefacts.

Losses included Egyptian and Greco-Roman relics acquired by the Brazilian imperial family, a large dinosaur named Dinoprata, and invaluable records of Indigenous life and culture in pre-colonial times.

Efforts are now under way to rebuild the collection ahead of the museum’s planned reopening in April 2026. Reconstruction works on St Christopher’s Palace began in 2021. The restored facade and front courtyard were unveiled a year later, but works continue on the rest of the building.

“It was an enormous tragedy but we need to look ahead and rebuild the institution. Brazil needs its national museum back,” Alexander Kellner, the institution’s director, told reporters on Tuesday, celebrating “this magical moment of the [fossil] donation”.

It is the most important donation of fossils received by the museum in recent history and of vital scientific significance, he said.

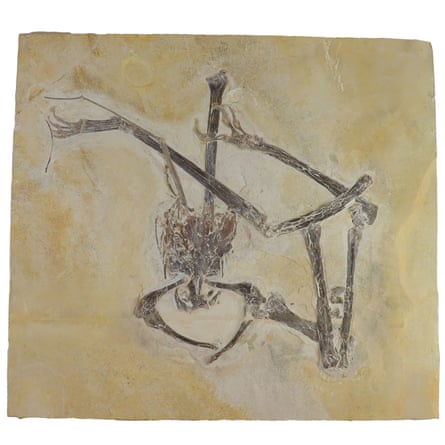

The 1,104 fossils donated by the Swiss-German collector Burkhard Pohl all originate from the Araripe Basin, an area spanning the states of Ceará, Pernambuco and Piauí in north-eastern Brazil where two geological formations contain palaeontological material from the Early Cretaceous period.

The donated specimens include two unique dinosaur fossils, a Tetrapodophis – possibly the earliest snake fossil – and two unstudied pterosaur skulls. They will be on display in future palaeontology exhibitions as well as contribute to scientific research at the museum, which is part of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

As part of a collaboration between the museum and Pohl’s Swiss-based Interprospekt Group, UFRJ palaeontologists and students are taking part in excavation expeditions in Wyoming and Montana in the US, in the hopes of discovering dinosaurs which could later be displayed in Brazil.

The fossil donation was mediated by the arts patron Frances Reynolds, who is spearheading a campaign to mobilise the public and private sectors, and rally collectors and enthusiasts to contribute to rebuilding the National Museum’s vast archive.

“You can have a great building but without a collection, a museum is nothing,” said Reynolds, who is president of the Instituto Inclusartiz cultural foundation.

The aim is to have gathered about 10,000 objects for exhibition by the time the museum reopens, Keller said, about twice the size of the display before the fire. He estimates the museum currently has about 2,000 pieces.

Digital versions of destroyed pieces will also be included, although their loss is “irretrievable”, said Keller.

“We can’t recreate what was lost, but we can show new objects. Various people have already made donations,” he said, citing the gift of an original portrait of Maria Leopoldina, Empress of Brazil.

Last year, the National Museum of Denmark announced that it would return a Tupinambá mantle, a rare Indigenous red-feather cloak that has been housed in Europe since the 17th century, and donate it to Brazil’s National Museum.

The institution’s Indigenous ethnology section suffered particularly severe losses and researchers are working closely with Indigenous Brazilians to ensure the reconstructed collection includes their perspective.

Reynolds, an Argentinian national but Brazilian “at heart”, said she was in constant discussions with governments, public and private museums, and private collectors to source new artefacts through donations or long-term loans.

“It’s just the beginning, this is the first chapter of many years of work in many parts of the world. It’s a legacy that we’re building for future generations,” she said.

Source: theguardian.com