Kathleen Byron and David Farrar were unforgettable presences in the 1947 Powell and Pressburger classic Black Narcissus, playing a hysterical nun and the taciturn colonial agent with whom she is peevishly infatuated. The film-makers reunited these remarkable performers two years later for this intimate, intense wartime drama thriller; brilliant on the emotional misery, low-level dread and petty office politics of wartime government. It takes place mostly in London’s noirish darkness and rain, except for the sensational final sequence in the bright sunlight of Chesil beach in Dorset.

Adapted from an autobiographical novel by military scientist Nigel Balchin, The Small Back Room is a work that shows the film-makers pushing – brilliantly – at the conventions and constraints of a regular wartime period drama. Any number of British directors might have wanted to take on this story. But the Powell and Pressburger authorial flourishes are irresistible.

Farrar plays a role not so very far from his Mr Dean in Black Narcissus, moody and saturnine. He is Sammy, a civilian scientist, or back-room “boffin”, working for a Prof Mair (Milton Rosmer) in 1943 in an ad hoc research department set up by the war office. Sammy is depressive and an alcoholic, driven to despair by incessant pain from a prosthetic foot which, through vanity and stubbornness, he refuses to take off in the presence of his girlfriend, Susan, his boss’s secretary, radiantly played by Byron.

In truth this is not as interesting a part for Byron, who is more softly and gently shot and lit than in Black Narcissus, but she brings warmth to a saintly role. Susan lives next door to Sammy, and part of the poignancy of his refusal to remove the fake foot lies in the implication that, for all their quasi-domestic intimacy, they may not yet have slept together – or if they have, the experience has been as tense as everything else in their relationship. Certainly, office politics mean that they cannot openly acknowledge that they are together.

The story begins when a personable young officer, Capt Stuart (Michael Gough), asks Sammy for his help in finding ways to deactivate sinister new booby-trapped devices that the Nazis are dropping during their air raids. And in this quest lies the film’s subtle, brilliant tension: how did Sammy lose his foot? No one ever says. But by the story’s end, the answer is plain enough. So far from being a back-room boy, Sammy is a courageous man of action. He may have lost his foot, but not his nerve.

Set against the clarity and urgency of the military mission is a backwash of pettiness and intrigue, a series of insidious problems as dangerous but innocuous-seeming as the Germans’ nasty little unexploded bombs. Sammy loathes the civil servant in charge, RB Waring (Jack Hawkins), a time-server trying to push through a new kind of artillery gun in the face of military scepticism and Sammy’s own research indicating that the weapon is ineffective. Prof Mair’s own position is dependent on the continued existence of a certain pompous War Office minister (Robert Morley), whose imminent sacking may herald a top-down change of personnel. Sammy is too grumpily self-pitying and proud to fight for his department’s existence, or indeed to jockey for the top job himself.

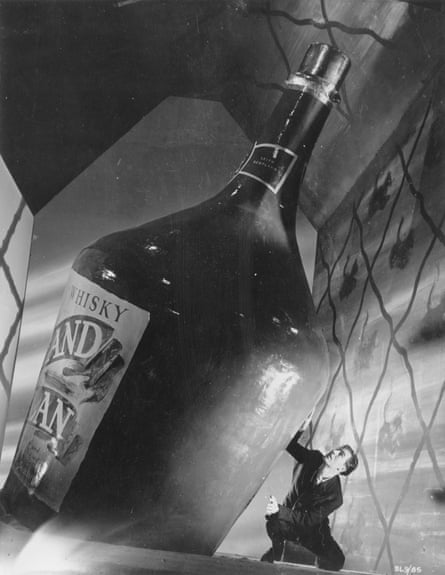

This all comes to a head in an extraordinary committee room sequence in which the top brass and the civil servants have an ill-tempered discussion in the presence of a framed photograph of Winston Churchill, the statesman who of course famously tried to scupper, on patriotic grounds, the Powell and Pressburger satire The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. The wretchedly formal and conceited waffle is almost inaudible against the background of drilling and construction work taking place outside. We absorb the incompetence and absurdity of all this as the camera tracks along the stuffy faces. It is an almost surreal scene – although the really surreal moment, perhaps inspired by Hitchcock’s Spellbound or Wilder’s The Lost Weekend, comes when Sammy has a near breakdown trying to resist the lure of whisky.

The final scene is notable for a vivid new character: a gutsy, forthright and kittenishly beautiful ATS corporal (Renée Asherson), who has to relay on a radio headset all of Sammy’s debonair commentary as he crouches all alone on the beach, defusing a bomb. It is a character to compare with Kim Hunter’s US air force radio operator talking to David Niven at the beginning of A Matter of Life and Death. The strength and confidence in Powell and Pressburger’s film-making is a pleasure – as is their distinctive love of adventure and romance.

Source: theguardian.com