Even before March this year, when gun-toting gangs overran the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince, dictatorships, poverty, health crises and earthquakes had defined the country in the eyes of global media. It passes for the archetypal failed state, a place where Unicef has declared that 3 million children urgently need humanitarian aid. Yet there is an alternative to this narrative of disaster and chaos: the beauty of Haitian culture. Music and visual art remain enduring symbols of hope.

Over the years, the population and its diaspora in North America have been extraordinarily creative. In the 80s, Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose father was Haitian, took the art scene by storm with his outre graffiti, otherworldly painting and barbed political commentary, while today Haitian-born artists Myrlande Constant and Frantz Zephirin are producing exhilarating canvases. Between the 1950s and 80s, musicians Nemours Jean-Baptiste, Coupé Cloué and Boukman Eksperyans excelled in genres such as compas, manba and rasin, which all have entrancing dance rhythms derived from Africa and provocative lyrics in the Creole language born of contact between French settlers and enslaved people.

Then, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, a major name in hip-hop was the Haiti-born, New Jersey-raised rapper-producer Wyclef Jean, who made his breakthrough as a member of the Fugees. Quite audaciously, he ran to be president of Haiti in 2010, though his candidacy was rejected because he had not been a resident for more than five years.

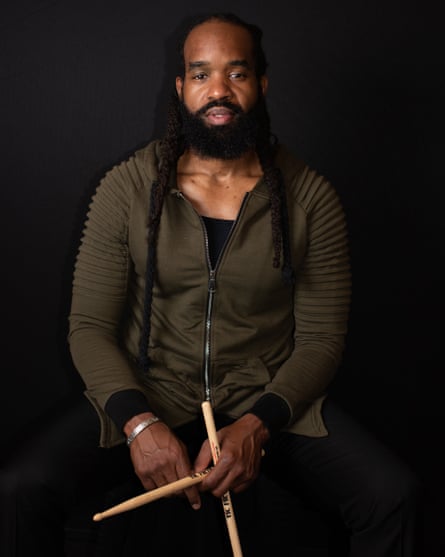

Today, the talent pool continues to flow through cities such as Miami, birthplace of Obed Calvaire, a jazz drummer who draws greatly on Haitian rhythms in his music. “I raise my head high, saying that I have Haitian roots!” he declares. “When you hear great African artists like Richard Bona say there is a distinctive Haiti sound in the way we play guitar or drums that’s like no other place in the world you’ve got to be proud of that. You got to be proud of all the music that has come out of our country.”

Calvaire’s new album, 150 million Gold Francs, is a highly political work. Its title refers to the sum sought by imperial France in “reparations” from the enslaved African people in Haiti, after they staged a revolt in 1791 and created the world’s first black republic.

Its release is timely given the longrunning tentacles of financial exploitation and corruption from inside and outside the country that form a backdrop to Haiti’s current plight. “We had the dictators Papa and Baby Duvalier,” says Calvaire. “But when he was president of America, Bill Clinton flooded the country with cheap rice and local farmers couldn’t survive, so we depend on the States for things we could grow ourselves. The US has a lot to do with the appointment of leaders; they didn’t want another Cuba. There’s still a bit of the slave mentality, we’re still in shackles.”

Yet there was a more positive side to Haiti’s relationship with the US. New Orleans, the cradle of jazz, was greatly influenced by Haiti’s ex-slave population, while the revered jazz drummer Max Roach went to Haiti in the 40s to learn its complex rhythmic traditions. One of his significant students, Andrew Cyrille, born in New York to Haitian parents, has been an indefatigable presence in avant garde music since the mid-60s and is still recording and performing at the age of 84. In 2011, he released an album, Route De Frères, that emphatically celebrated his heritage.

On the album, Cyrille recorded original music but also highlighted the beauty of Haitian folk songs and the spiritual practice of vodou, which, far from the western stereotype of dolls, pins and spells, is predicated on transcendence and healing by way of drumming, chanting and dance. Other modern Haitian-American jazz artists, such as Cécile McLorin Salvant, a singer and painter, whose brilliant 2023 album Mélusine notched up two Grammy nominations, see the importance of these cultural foundations.

“I am learning more and more about vodou and feel extremely drawn to it,” she says, also recognising the richness of the iconography that accompanies the faith. “I think I am connected to these images, even without knowing them.” Obed Calvaire, who appears on Mélusine, explains how Haitian spirituality shapes his work. “My rhythms are from vodou ceremonies, I just play them on the different parts of the drum kit.”

Haitian-Canadian saxophonist Jowee Omicil’s album SpiriTual HeaLinG Bwa KaYimaN FreeDom SuiTe is notable for its ingenious blend of vodou and the history of revolution on the island. The music, which also has echoes of American and Caribbean avant garde artists such as Ornette Coleman and Jacques Coursil, was spontaneously composed during a rehearsal in which horns, keys and percussion blended together in a suite that ebbs and flows through abstract soundscapes and taut grooves.

The music has the engrossing ambience of both timeless ritual and redemption song. “All the ceremonial rhythms I use have a deep meaning,” says Omicil. “In Haiti, slaves came from Guinea, Togo, Congo and Benin … they came with their rhythms. They had to unite and fight for their heritage. The sounds of freedom are what people were afraid of. We have all these traditions that are used to open different doors for us to uplift each other through music and ceremonies. They are sacred for us.”

Needless to say, Omicil, like all members of the Haitian diaspora, is greatly concerned by recent events on the island, where he has family, and is intent on performing there when possible in order to provide solace to the population. He is keen to use his music as a counterweight to the prevailing image of his heartland as an irredeemable modern-day disaster zone, but he also points to machinations unfolding behind the scenes that would keep it thus.

“The question is, who is benefiting from what Haiti is going through?” he asks in emphatic rhetoric. “It’s not the Haitian people. We don’t make the weapons that are coming into the country. Two Canadian gold companies have just signed contracts to mine on the island because there’s so much gold. Who benefits? It makes me so sad, which is why I fly the flag for Haiti even though I was born in Montreal. I have everything to do with Haiti. I have to take care of my roots; that’s what the music is doing, because we’ve been oppressed. That’s why my music is about coming together to uplift and heal, I’m not a politician but I feel I can impact people through music.”

“L’union fait la force”, the motto on the Haitian flag, translates from French into English as “Strength in unity”, and that resonates with many Haitians at this point in time. Still, Obed Calvaire sounds a note of caution. “Yeah, I feel the idea,” he says. “It would be great if we could all do something together, maybe raise some money for the cause, but then you go back to the earthquake [of 2010], and we raised how many billions of dollars? Where did that money go? Is there an honest leader to use it well?”

For all these misgivings, Calvaire welcomes the prospect of artists joining forces for the good of Haiti. “We could still form a collective, and make some beautiful music for the people.”

Jowee Omicil plays Ronnie Scott’s, London, on 30 May; Obed Calvaire’s 150 Million Gold Francs is out now on Ropeadope; Mélusine by Cécile McLorin Salvant is out now.

Source: theguardian.com