In the Jordanian town of Tafilah, a six-year-old boy softly hummed a song. His family were astonished, and his 82-year-old great-grandmother, Jawaher Al Ahmad, overheard and began to cry. She asked the child who had taught him the “hajini”, or Bedouin folk song, and said: “The last time I heard that song was at my wedding.”

Her great-grandson, Ahmad, had learned the tune as part of the I’m My Voice project run by Tajalla for Music and Arts, a cultural organisation founded by Russol Al Nasser.

“Singing has always been an integral part of our daily life, closely intertwined with agriculture,” says Nasser. “Our grandparents sang while planting, cultivating and harvesting. We had folk songs for weddings and others for mourning.” However, according to Nasser, rural-to-urban migration, and the diminishing role of agriculture, has meant “altering our rituals, causing us to lose pieces of our heritage”.

Tajalla’s projects are based on the idea that arts and culture play a vital role in daily life, creating a connection with the environment. The I’m My Voice project began in 2018, establishing children’s choirs in different cities across Jordan to preserve oral heritage.

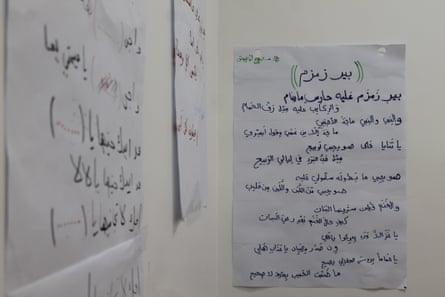

The first stages involved field research. Tajalla volunteers sought folk songs from diverse regions. “We searched for ladies over 70 in the communities and visited Bedouins in the south. We sat, had tea, chatted, recorded what they shared and sang,” says Nasser. As a result, 43 songs were collected, including Ahmad’s great-grandmother’s wedding song, Beri Zamzam.

The research extended beyond Jordan’s borders, disregarding the British and French colonial boundaries that divide the fertile crescent. The 43 songs came from the Hauran valley, spanning parts of Syria and northern Jordan, as well as Badiya, the desert and semi-desert that spans southern Syria, eastern Jordan, northern Saudi Arabia, and western Iraq.

However, the lyrical complexity and sophistication of some folk songs had their challenges for modern ears. “We were not expecting it to be difficult to understand some of the songs’ lyrics and follow the rhythm,” says Nasser.

Tajalla’s team proposed minor tweaks and developed a child-friendly curriculum, while preserving as much as possible of the oral heritage. Nasser says: “Our priority is to be inclusive. We don’t hold auditions, and possessing a melodious voice isn’t a prerequisite to join our choirs.”

Yaqeen, 14, from the town of Wadi Musa, has been part of the weekly choir for three years and loves learning the old songs. “She reminds me of my childhood,” says Yaqeen’s mother, Um Mohammad, who says: “This project has bridged a generational gap; youngsters now sing along to our heritage songs at weddings with their grandmothers.”

Rand, a 10-year-old from Karak, is another keen singer. “We went on a family picnic to the Dead Sea once. I sang in front of the whole family: my grandmother, grandfather, uncles and aunts. When I started singing the Beri Zamzam song, my grandmother was surprised, but then she joined in, and we sang together.”

More than 170 children have taken part in performances. Tajalla members have also been crafting online content merging original audio of elderly voices with children’s singing.

One sad aspect has been losing grandmothers who played a crucial role throughout the project. Since it began, three of the older women have died. “We had plans to revisit these ladies with the kids,” says Nasser. “Allowing them to sing the songs they taught us. Their absence has highlighted the urgency in preserving our oral heritage as swiftly as possible.”

Rawan Baybars is from Amman, Jordan, and is part of an ifa.de programme assisting civil society journalists around the world

Source: theguardian.com