In increasingly turbulent times for the music industry, one aspect has remained steadfast: its passion for stats. At the start of the decade – with YouTube a strong metric of success after the collapse of CD sales – you couldn’t move for mind-bending figures being trumpeted about music video viewership. In 2021, for example, K-pop boyband BTS’s Butter video amassed a staggering 108m views in 24 hours, breaking a record that appeared to be eclipsed on a weekly basis. Butter now sits on a not-too-shabby 950m views, a figure dwarfed by Katy Perry’s jungle-based Roar (3.9bn), Mark Ronson’s retro fantasia Uptown Funk (5.1bn) and Luis Fonsi’s Justin Bieber-assisted 2017 smash, Despacito, which has 8.4bn views.

The two dominant global forces in recent years have been K-pop and Latin music, and their big-budget music videos still rule the roost (Shakira and the Colombian singer Karol G’s TQG video was viewed more than a billion times last year). For Anglo-American pop in 2024, however, a seismic shift has occurred: music video viewership has plummeted, Beyoncé and Drake have stopped releasing videos altogether and pop’s A-list are struggling to make a dent on a platform they previously dominated.

Since its release in November last year, the video for Houdini – the long-awaited lead single from Dua Lipa’s third album – has been viewed 93m times, making it only the 27th biggest of her career. Ariana Grande’s Yes, And? clip is only on 51m views after two months; she has eight hits with over a billion. Ed Sheeran’s 2023 Eyes Closed video, meanwhile, is stuck on 77m views. Even Taylor Swift – who essentially is the music industry – isn’t immune, with Anti-Hero, the lead single from 2022’s Midnights, on a so-so 192m views. No one is suggesting any of these artists are flopping – Anti-Hero’s Spotify streams stand at 1.4bn, while each of the songs mentioned peaked at No 2 or higher in the UK – but tricky questions remain: is the music video dying out? And if so, what’s killing it?

“Asking people to stay on one page for the full length of a track in an era of scrolling is really difficult,” says Hannah T-W, an artist manager and the former head of music videos at production company Somesuch. “It’s now not a normal viewing practice. People are used to much shorter clips and devouring things really quickly.” Those “much shorter clips” proliferate due to the music industry’s latest obsession, TikTok, where songs provide backing music to user-generated clips, or as #content performed by pop stars almost through gritted teeth. Gone are the halcyon days of making a single, getting it to radio, chucking it on MTV and sitting back to watch it fly. “We’re living in a media consumption age where you have to compete with everything, everywhere, all at once,” says the creative director and music video director Bradley J Calder. “You’re not just up against other music videos, but Netflix, Spotify, TikTok and your own camera roll on your phone.”

There’s now a ripple effect: the drop in viewing figures has meant a drop in video budgets, which in turn can squeeze creativity. “The kinds of briefs I’m seeing now are mind-blowing,” says the director and photographer Olivia Rose, who has worked with Anne-Marie and Jorja Smith. Five years ago, she says, £30,000 would have got you a decent video, but now directors are being expected to use that money for “three visualisers” – the looped images or clips used as placeholders on YouTube – “for three tracks, plus TikTok content and some stills, plus the video”. While creativity can still thrive with tighter budgets, quality can suffer as directors’ skills are stretched. “The music video historically has been, and still is to this day, an art form,” Rose says. “And we’re losing it.”

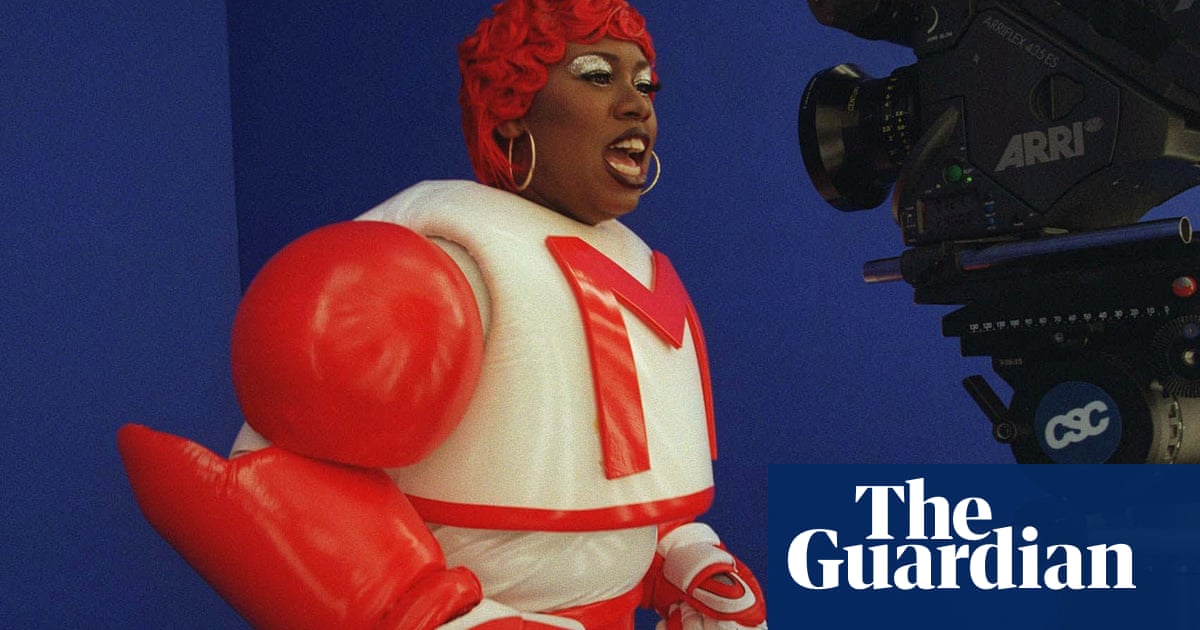

It is an art form that has the ability to create instant visual iconography (think Smells Like Teen Spirit or … Baby One More Time), cement artists as visual innovators as well as musical ones (see Björk’s mind-bendingly outre aesthetic or Missy Elliott’s splashy, DayGlo surrealism) and create such anticipation that video premieres become watercooler moments. (One office I worked in came to a standstill so everyone could watch the YouTube premiere of Lady Gaga’s Bad Romance, a pricey visual feast of white latex, Thriller-esque choreography and bed-based incineration.) It was also an art form that was amplified by 24-hour music channels. Many of those are now long gone or going – Kerrang! TV, Kiss TV and The Box will all be axed this year, owners Channel 4 announced in January – and YouTube algorithms seem to favour the company’s own shortform platform and TikTok rival, Shorts.

One man who has seen the rise and fall of music videos before is Mike O’Keefe, vice-president of creative at Sony. “Music videos have been my career for the last 35 years and I still think it’s an important part of what an artist does,” he says, while admitting that there has been a drop off in numbers. TikTok, he says, is great at helping to share songs, but he is less enamoured of its ability to create visual worlds. “Tracks on TikTok can be successful with user-generated content visuals – it’s not representative of the artist in that sense.”

Lil Nas X has released four videos that have been watched more than 500m times. But despite teasing his controversial new single J Christ – a broadside against the US religious right – for weeks on TikTok, the single bombed and the video plateaued at 18m views. The very online rapper will be au fait with another way to signpost a video’s existence, via memeable moments. O’Keefe confirms these are now being written into the briefs sent out to directors in the hope they will catch tired eyes and turn casual scrollers into fans. As Hannah T-W explains: “You do think about these things when you’re going into those massive music video moments: what’s the money shot of the music video, to use a horrible term?”

after newsletter promotion

Sarah Boardman and Joceline Gabriel, who represent a host of music video directors through their company Hands, cite both general “oversaturation” of visuals and the fact that views are now being split across lyric videos and visualisers [simplified teasers for songs] “and the main video itself” as factors affecting music videos today. They also touch on perhaps a more concerning issue for the industry at large, one involving the “rarity of seeing a new artist with real charisma and hearing a really good track that doesn’t just follow a trend”. With thousands of new songs and videos being uploaded each week, cutting through the noise has become more and more important.

“We’re hungry for greatness right now,” agrees Calder, whose work on the Canadian pop star Tate McRae’s recent album campaign – including sleek and stylish performance-based visuals that recall 00s Britney and look like, according to Calder, they “belong on MTV, not on TikTok” – has bucked the trend of diminishing returns from videos, and elevate McRae beyond pop’s mid-tier. “I don’t think the music video is dead; we just want it to be better,” he continues. “We’re living in a pop desert right now where nothing feels too exciting.”

So what’s the solution? How can the music video survive a fractured ecosystem that’s being bombarded with snacky visuals? “It’s about readdressing the music video as the art form it is,” says Rose. “So making fewer of them, with more quality.” Calder, meanwhile, thinks the creative bandwidth of a new artist should be split equally between music and the visuals: “In this day and age every artist should be a visual artist.” Perhaps it’s as simple as ignoring play counts altogether and focusing on more engaged viewers, suggests O’Keefe: “We’re obsessed with views, but the actual numbers are misleading: it’s about engagement. Music videos are important to the artists and the fans, but possibly less important to the casual viewer.”

For the cautiously optimistic Boardman and Gabriel, this is all part of the cycle of an industry recalibrating itself after the explosion of a new medium. While we may never see such a heavy bombardment of record-breaking YouTube stats again, a great music video can live on well beyond those first 24 hours. “To be a blue plaque artist you will always need [music videos]; the TikTok stuff won’t stick in people’s memories for 40 years, that’s for sure. Maybe a day if they are lucky!”

Source: theguardian.com