Joe Lycett and Robbie Williams were brought together by Instagram. Last August, Williams posted a painting of a small, saintly looking child (not him), and captioned it with an account of how he had once made the mistake of reading the comments below a Mail Online piece. “It was hellish,” he wrote. “The person (me) they were describing was the most horrendous person that ever walked the planet. I was crestfallen.” At this point, Williams thought the best plan would be to read some comments about people who “are good, salt-of-the-earth folk”. So he looked up a piece about Ant and Dec. “Surely to God no one can hate Ant and Dec,” he thought to himself. But no. “The second comment said: ‘I hate these two almost as much as I hate that fat c*** Robbie Williams.’”

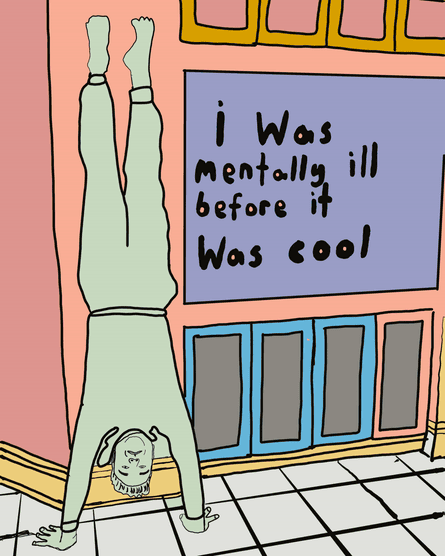

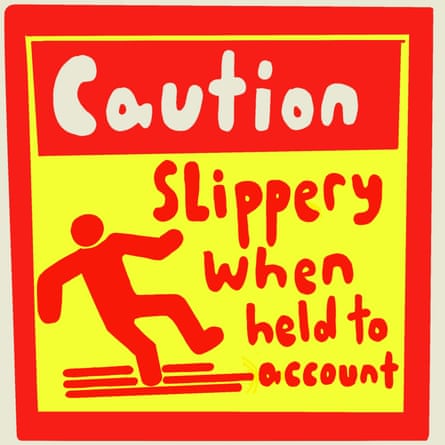

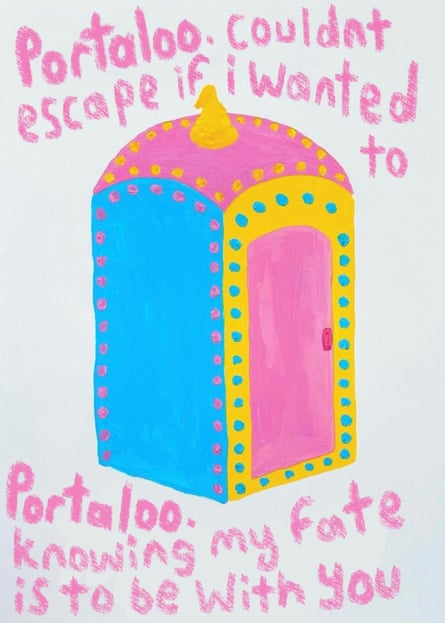

Among those who replied to his post were Alan Carr, Piers Morgan, and Lycett, who said it made him laugh out loud – and so began their (possibly somewhat unlikely) friendship. The comedian also paints and makes ceramics (you can see his “after Hockney” portrait of Harry Styles, a rude vase he may – or may not – have designed for H&M, and several other works on his website); in 2018, his sculpture Chris was accepted by the Royal Academy for inclusion in its Summer Exhibition. By September, Lycett had visited Williams at home in west London, at which point they discovered how well they got on, and how similar their art is. Williams’s Inklings illustrations, like Lycett’s huge acrylics, have a pop art sensibility that pokes fun at celebrity culture and the so-called wellness industry.

For this interview, Lycett and Williams talked over Zoom. Lycett, who is 35, was at home in Birmingham, in a pink room with a big cupboard in which he houses some of his beloved outlandish stage outfits; Williams, 50, was in London, where he lives with his wife, Ayda Field, and four children (one of whom appeared fleetingly on screen). Their conversation touched on dating, artificial intelligence and the nature of fame, as well as some scabrous celebrity gossip that it would probably be extremely unwise to repeat here.

Joe Lycett:

You started posting art on Instagram last May. Is that right?

Robbie Williams:

Yes. I’ve been doing stuff [making art] since 2006, but I hadn’t put anything out there.

But then I had this joke about the Olympics/the Ozempics [the weight-loss drug], and for some reason I was worried. I thought: “I must put this out there now, or someone else will either steal it or think I’ve stolen it.” I wasn’t planning on following it up but I got such nice comments – and that fed my ego. I thought: “I’m going to do some more of these. People are pleased with me.” As of today, that joke has had 15,746 likes. I don’t do photographs of me on tour any more, really. It’s all the art. Before this, I didn’t really do social media. I’ve always been puzzled by it. I exist in a very 90s personality, one who doesn’t get it at all.

JL: Hang on. Aren’t you on Twitter?

RW: No, I’m not on Twitter [now known as X]. It would ruin my career. The last time I was on it, I did a tweet that said: “I quite fancy getting into shoplifting. Has anyone got any good suggestions for shoplifting?” The person who runs Gail’s, the bakery, said: this is awful. This is a pop star who lives in a bubble. How dare he? I saw the backlash, and I was, like: “I don’t think Twitter is for me.” I got my fingers burned.

JL: But that’s increasingly what it’s like out there. It’s weird for me because when I was starting out as a comedian, before I had any recognition, I had maybe a few hundred followers, and I would use it to try out jokes. It was a kind of writers’ room, all these half-baked ideas. But looked at retrospectively, with a few more followers, it’s a writers’ room full of danger. But the shoplifting stuff, that’s interesting. Are you familiar with the artist Foka Wolf [the Birmingham billboard prankster ]? He has a whole strand of work about shoplifting; he says it should become more normalised. You’re in a similar space.

RW: I’ve just had a look at his Insta page, and I already like it. But I’m Robbie Williams, so I’m in a certain box. I’m in a pop star box, and if the pop star starts acting differently from the way a pop star should, then it causes confusion, which I like, but it might also get me cancelled.

JL: One thing I’ve noticed about your art is that nearly all of it is funny. Is that something you feel you can’t do through your music? I mean, there are elements of humour in your lyrics, but they’re more amusing observations than punchlines.

RW: OK, so when I was 10, and at primary school, we camped in north Wales for seven days. At the end of the holiday, we were allowed to go into town and some people had some pocket money and some people didn’t; I didn’t. Anyway, we were in the shop, and I saw this poster on the wall. It was of a train that had crashed because a bridge had collapsed. It was the 1890s or something, and there was this man with a big top hat on, and he was looking at the scene, and it just said [what he was thinking, which was]: oh shit, oh shit. I thought it was the funniest thing I’d ever seen, and I stared at it for ages and ages. There was also this book, again when I was about 10, of funny things people had written on walls. I guess both those inspired me to do what I’m doing now. I don’t know if there’s something about not being able to be funny in my music; it’s not like I’m burning to do more funny lyrics. But in this medium, I’m still that 10-year-old.

JL: Even in my world, if you’re a musical comedian, people roll their eyes a bit. Music isn’t the place for funny.

RW: It’s kind of like a prop gag, isn’t it? Where I peaked with this (funny lyrics) was my song Rudebox [from 2006]. It was meant to be whimsical and silly, but it was just deemed silly and was vilified.

JL: It’s sort of what you were talking about before: about being in your box. Doing something different isn’t allowed.

RW: I’m a big fan of surreal, of whimsy, and I don’t think the music world takes to silly very well. It’s either Barbie Girl, which we all get is silly, or it’s not understood or appreciated.

JL: Comedies never win Oscars.

RW: Neither do action films. But I enjoyed the last Mission Impossible way more than I enjoyed Oppenheimer. It was incredible escapism. But it won’t get anywhere near the Oscars, because action is deemed a lesser art form – which is why I went on my Instagram with one of my signs on a stick outside the Beverly Hills Hotel that said “Give Tom Cruise an Oscar already.” Just give him the frigging Oscar, you pretentious clowns.

JL: Do you think he was appreciative of that?

RW: Well, I haven’t heard from him. But I really meant it, and I will forgive Tom Cruise anything because he’s amazing. So it’s all good.

JL: At what stage did you decide to get in touch with me? What was the trigger?

RW: The trigger was seeing you on television and liking what you do, and then it was to do with my art, and me thinking: “Oh, Joe’s doing this too.” So I reached out. People do reach out on social media, don’t they? It’s the artistic equivalent of sliding into someone’s – what’s it called? – DMs. I missed the whole sliding-into-DMs-phase, because I’ve been in a relationship with my wife for 18 years. Thankfully, I’ve never had to deal with that.

JL: It is dangerous. I’m also, as you know, in a long-term relationship now, so I don’t need to worry about it. But when I was [single], I didn’t slide into people’s DMs. It was using Hinge and Grindr and those apps, and people would screenshot and then post the chat you were having with them. I’m not a good flirt, so people seeing my blurts was…

RW: Yeah, that’s abusive and unkind.

JL: So, the art…

after newsletter promotion

RW: Yes. I’ve got these Inklings that I do. I’ve got 2,500 of them, but not all of them are Instagram grid-worthy. I post every day, and now I’ve got slight anxiety that I’m going to run out of good ones to put up, but I am enjoying the process. I’ve got to draw some more, or come up with other things to put on the grid, and since I am an addict [Williams has struggled with drugs, alcohol, food and prescription drugs], I guess I’m addicted to social media right now. There’s your headline.

JL: [Laughing] Well, I concur. Because I think Instagram has made me more prolific as an artist. You get that dopamine hit from the response, and you want more of that, so you make more art. There was a piece – the one I spent the longest time on. It was a painting of Jenny Beavan [the Oscar-winning costume designer], who I live with when I’m in London. I spent ages on the folds in her jeans and it got much less engagement than stuff that had taken me 10 minutes. I found it frustrating. It was annoying. But still, without Instagram I would probably make a lot less art than I do.

RW: I also spend a lot of time on my captions, which have become diary-like, and what I noticed was that nobody was talking about my Inklings. They were responding to what I’d written. I was feeling like my Inklings were being ignored! I put a PS on one of my captions: can someone say something about my Inklings please?

JL: Yes, I’ve been writing silly blocks of text – flights of fancy essentially – about where the paintings come from, and you’re right, they become bigger than the post itself. But when you’re making art, is there a mental health benefit too?

RW: I was with Vic Reeves in, probably, 1995, and he told me that he creates something every day, and I remember thinking: “If only I was talented, I’d do that.” And now I find myself creating something every day, and escaping into creation in my mind, and the more time I spent doing that, the less time I spend self-sabotaging, or thinking about all the anxieties of life, the foibles of being me and inside my brain.

JL: I read somewhere that one art experience per month can add up to 10 years to your life – and it doesn’t have to be good work; there is no correlation between the quality of the work and the benefits.

RW: Wow. In that case, I’m going to live until I’m about 130. But it’s so gratifying and I’m so lucky to have the time to do it. It gives me dramatic purpose and I feel very, very fulfilled. I don’t know how I existed without doing this. When I was trying to put an album together, you have a couple of days writing songs, and then you might do nothing for a couple of months, and I don’t know what I did with myself in between. I got on the plane back from Hong Kong recently, and it was a 14-hour flight, and I spent 12 hours of it creating this jacket [a patchwork garment he’s designing]. I didn’t switch on the TV.

JL: The art changed for me when I had a chat with Mr Bingo [the illustrator and artist]. He gave me the idea of selling prints of my work in lockdown, and now it has become another revenue stream for me. It’s a bit of a machine, rather than the mental health thing it was.

RW: I’m addicted to the win – and how is the win measured? Eventually I will make my Inklings available to buy. It’s not just the money going into my bank account; it’s more to do with people liking them. I don’t suppose you’re allowed to say that as an artist. But if I’m not going to be lauded as a credible artist, I’ll choose to be a commercial one instead.

JL: I haven’t asked you about your exhibition in Amsterdam. How’s it going?

RW: Really well. It felt really good. Instead of having an existential crisis, which is what usually happens, I just thought: I don’t know what this means, but it’s nice.

JL: I did an exhibition last year with my mum [Helen, a retired graphic designer], and what was strange about it was you have all the build-up, like you have for a gig, the same kind of nervousness, the build-up of adrenaline. But there’s no performance. The showing-off has been done already.

RW: I didn’t have any nervousness. The exhibition isn’t going to facilitate the future of my children and our lifestyle. I did read some comments from the museum, and they were all very nice, apart from one that said, ‘People spend years studying fine art and they can’t get anywhere and Robbie Williams does some doodles and he’s in a museum.’

JL: We’ve got to finish this in a minute, and we should talk about Birmingham before we do. You grew up in Stoke, I know, but I am wondering if you have any links to Birmingham, especially to do with art in the city.

RW: Well, the only thing that comes to mind is Miss Moneypenny’s, the club. It was pivotal for me. I went from being this good boy in a Catholic school in Stoke to being this person who had just bombed a gram of speed and had three E’s in my pockets, dancing in my Vivienne Westwood bondage trousers and shirt with a high collar and tie that had the same gingham pattern. I went with a bunch of people from Warrington who would rent a van, and they would pick me up at a service station, and off we would go.

JL: Wow! I’ve literally never heard of it. I can’t believe I don’t know it… it’s got its own Wikipedia page.

RW: I remember spending a lot of time in gay clubs. For the first 18 months of Take That’s existence, we did gay clubs. I had the best time, because you weren’t in fear of your life. The love and acceptance that I found there, I will always be grateful for it.

JL: I feel the same. Any city I go to, they’re a safe space for me: a haven.

RW: Anyway, I’m away for two weeks, and then I’m back in London. I’d love to see you then, Joe. I do really enjoy your company – and hopefully neither of us will be cancelled after this appears.

JL: Yes. Fingers crossed!

-

Robbie Williams’s first solo show, Pride and Self-Prejudice, is on at the Moco Museum in Amsterdam until 8 July

-

Late Night Lycett airs Fridays at 10pm on Channel 4. The book Joe Lycett’s Art Hole is published later this year and is available to preorder now

Source: theguardian.com