The biannual Journal of Beatles Studies was launched by Liverpool University Press in October 2022. The peer-reviewed publication aims to “inaugurate, innovate, interrogate and challenge narrative, cultural historical and musicological tropes about the Beatles”; as such, it is a natural byproduct of the MA in Beatles studies also offered by the university.

No doubt one strand of that course, in the manner of “What were the causes of the great war?”, will necessarily be devoted to: “Seven-year itch: was the Fab Four breakup inevitable?” If so, this collection of interviews, apparently locked away for more than 40 years, will be required reading.

Co-author Peter Brown has all the necessary credentials of a key witness. He was hired by Brian Epstein in 1961, first to run his record shops, then to look after the day-to-day management of the Beatles. He became a close friend of all four – he introduced Paul to Linda and was best man at John and Yoko’s hastily arranged wedding in Gibraltar; he was also there in all the increasingly rancorous contractual meetings that, after Epstein’s drug-related death in 1967, made the end of the group inevitable.

Brown told this story, with the help of music writer Steven Gaines, in the 1983 book The Love You Make (at the time characterised by Beatles fans as “The Muck You Rake”). Reportedly, on receiving a copy from Brown, the McCartneys ceremonially burned the book, Linda photographing the remains. This volume is something like the director’s cut of that book – the transcripts on which it was based, interviews not only with the principals in the drama but with 30 or more walk-ons in their personal and business dealings.

The interview with McCartney, conducted a month before the murder of Lennon, is instructive not only about the former Beatle’s state of mind a decade after the breakup, but also of the motivations of Brown and Gaines, whose lines of questioning are a clue to some of their preoccupations: the promiscuity of band members and their drug use, the behind-the-scenes tragedy of Epstein, the effect of the arrival of Linda and Yoko on John and Paul’s creative marriage – and above all the extreme acrimony over contracts and Apple business.

McCartney, with that familiar chummy candour, seems drawn into saying a little more than he might have been advised to by the presence of Brown, his old confidant. Here he is on Yoko, for example: “We didn’t like her at first, and people did call her ugly and stuff, and that must have been hard for someone who loves someone…” Some of his misgivings about The Love You Make were no doubt its focus on the sense of betrayal he expressed about Lennon at this point, which looked callous after Lennon’s death.

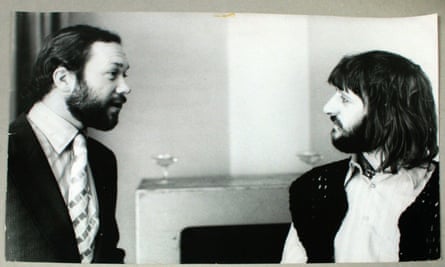

On this evidence, Gaines had little interest in understanding the pair’s magic, only their personal disharmony, which came to a head with Lennon’s efforts to impose Allen Klein as the band’s new manager. The interviewer seems keen to goad McCartney into revelation. “How come I never met a girl in America who said: ‘I had a great time with the Beatles?’” There is, too, a good deal of interrogation about how the band felt about Epstein being gay – “Were the guys put off by him at all?” – and about a two-week holiday Lennon took to Spain with Epstein, which fuelled persistent rumours about their intimacy.

The authors’ interview with Epstein’s mother, Queenie, is also brutally blunt about what is called “Brian’s problem”. Questioning her outright about whether she thought Epstein’s death was an accident or suicide, Brown suggests: “I don’t have any doubt that particular occasion was a mistake.” Gaines immediately counters: “Freud says there are no mistakes.”

That kind of inquiry sets the tone for much of the material here. Reading the pieces back to back you have the sense of Brown and Gaines jetting between London and New York, like hardboiled crime investigators, in search of evidence of ever more rancour between Klein and John Eastman or Cynthia Lennon and Yoko, all of them proxy battles in the primary war between Lennon and McCartney. The epigraph for this book is a 1972 quote from Lennon: “I’ve read cracks about, ‘Oh the Beatles sang, “All you need is love” but it didn’t work out for them’. But nothing will ever break the love we have for each other.” The cumulative weight of evidence here seems determined to prove that latter sentiment a lie.

In among Ringo’s stalwart loyalties (“I didn’t want to fight Paul ever”) and George’s attempts at deflection, by responding to direct questioning with freewheeling discussions of karma (“it’s like… when you are born you’ve got a bit of string with all these knots in it, and what you’ve got to try to do before you die is undo all the knots”), one of the more memorable exchanges is with Bob Wooler, a Liverpool DJ whom Lennon reportedly beat up because he “cast aspersions on John and Brian’s trip to Spain”. After being grilled at some length on exactly why “John Lennon punched you on the nose”, Wooler turns the inquiry around: “Peter, do you think you will still be friends with the Beatles [when this book comes out]?” You won’t need to be a close reader of the Journal of Beatles Studies to know the answer to that one.

Source: theguardian.com