The browbeaten striker looked forlornly to the floor, the whistles of derision ringing in his ears. The stadium may only have been partially full of travelling England fans but the seething frustration was unmistakable as their emotion poured on to the pitch.

Lining the sparse terraces draped in union flags, the ragtag collection of supporters – many of them shirtless – got as close to the pitch as possible to spew their thoughts at their own players.

England’s raucous band of followers had proudly sung about backing their team “over land and sea” only two hours earlier, but the tide had turned after what they’d witnessed.

The excesses of earlier in the day were now in plain sight. The vitriol normally saved for rival fans and players was raining down on their own countrymen instead, like volleys of friendly fire. Nobody was spared. Least of all the normally sharp-shooting marksman whose run without scoring for his country had stretched to yet another match.

He was pouring with sweat, white shirt and tight blue shorts drenched as a sign of his efforts, but Gary Lineker hadn’t seen any fruits for his labours. Neither had his teammates, much to the ire of the England contingent in the stands. The next day’s newspapers would describe the performance as a “disaster”, a “disgrace”, a “day of shame”. England had been tepid. Toothless. Benign.

Two matches into the 1986 World Cup and England had failed to win a game or even score a single goal. If that run stretched into a third match, then a talented squad would be on the next plane home. There, they’d be greeted by the ferocity they’d lacked so far in Mexico; an unforgiving crowd of fans would make their dissatisfaction known.

If the several thousand angry supporters in Mexico were making their feelings heard, the millions more at home watching grainy images that proclaimed “Inglaterra 0” for the second match running would be even louder.

The postmortem had started even before Bobby Robson’s men were dead and buried. If they got a win against Poland in England’s final group game, they’d still progress to the last-16 of the competition, but listening to the pundits on TV, radio and in newspapers, you’d think that another underwhelming display was a foregone conclusion.

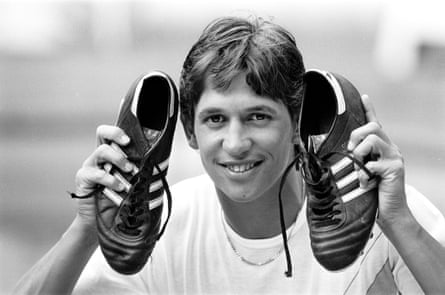

Questions were coming and Lineker knew some of them would be about him. The striker had been in irresistible form domestically all season, but his latest blank in an England shirt had meant he’d now gone six international matches without a goal. How could a forward who had plundered 40 goals for Everton in the past season look so impotent when playing for his country?

It wasn’t an unusual phenomenon. In recent years, England had a series of forwards whose careers had followed a similar trend, scoring freely in the First Division but never quite cutting it when they stepped up. It was starting to look as though Lineker might be the latest cab off the rank, another goalscorer who couldn’t hit the levels needed to succeed internationally. Perhaps it was time to go in a different direction.

England’s 0–0 draw with Morocco had been a low point. Lineker had tirelessly run the channels, fought for flick-ons from striker partner Mark Hateley, attempted to find pockets of space. There was no questioning his industry, but all he had to show for it was a first-half run into the box before being hustled to a tight angle away from goal and seeing his shot charged down by goalkeeper Badou Zaki.

It had been a similar story in the tournament’s opening match a few days earlier. A 1–0 defeat to Portugal had offered little in the way of goalscoring opportunities for Lineker. He’d toiled and scrambled, bumped and barged, but had cut a frustrated figure as the Portuguese stifled England’s attacking efforts.

When an opportunity did fall to the No 10, he squeezed his shot beneath the goalkeeper only to see the ball cleared by the desperate covering run of defender António Oliveira. The images of Lineker’s hands on his head and resting on his hips, blowing out his cheeks, were becoming all too common.

It’s true that the Leicester-born striker had hardly been swimming in a conveyor belt of chances supplied from the players behind him, but his trend without scoring had stretched back longer than just England’s disappointing start to the World Cup. He hadn’t scored in the four games leading up to the tournament, meaning he hadn’t netted since the previous year.

That hat-trick against Turkey, paired with a brace against the USA a few months earlier, papered over the cracks of Lineker’s early international efforts. Six goals in his opening 15 England matches was a respectable return, if not hugely prolific, but he’d only scored in three of those matches – failing to find the net on 12 occasions.

It was all well and good adding to his numbers against the weaker nations, but he needed to show he was more than simply a flat-track bully.

There were some pundits out there who thought Lineker should be one of a number of changes that Robson made to rescue his side’s ailing Mexico ’86 campaign. England’s 1966 World Cup-winning manager Alf Ramsey was one of them, using his Daily Mirror column to call for a new-look frontline that “would offer England a variation in their attacking ideas”.

Being dropped at this stage of his career would be damaging for Lineker. So when the team was revealed for the crucial final group game with Poland, it was a relief for Lineker to hear his name still in the starting XI.

after newsletter promotion

His strike partner for those opening two matches, Hateley, had made way for Newcastle United’s jinky creative Peter Beardsley, who – along with a handful of other changes, including Steve Hodge, Peter Reid and Trevor Steven – was expected to change the way England played. More speed and ingenuity should create a higher frequency of better chances for Lineker.

As he stepped on to the Estadio Universitario pitch in Monterrey, Lineker must have been aware of how important the ensuing 90 minutes would be for his England career. The sense of occasion must have been huge, even if the setting itself wasn’t.

Those same supporters who had been bubbling with resentment against Morocco were back again, gathered together to make the most noise they could muster in the vast, open-aired stands – creating a monophonic sound that echoed around the partly empty space.

England and Lineker couldn’t afford for the unusual atmosphere to impact the performance on the pitch. If they failed to score again and the Three Lions crashed out of the World Cup without getting out of the groups, then the criticism would grow, and the striker’s goal drought could be one of the reasons cited.

A match against Poland was no gimme, though. On paper, the Eagles posed much stronger competition than Portugal and Morocco had in the previous two games. They’d finished third at the 1982 World Cup four years earlier, only losing to eventual winners Italy, and had topped their qualifying group to be one of the top six seeds for the tournament.

After a win and a draw in their opening two matches in 1986, they only needed to avoid defeat to progress at England’s expense. The allowance for error couldn’t be thinner.

A little over half an hour after that career-defining match with Poland kicked off, Lineker was surrounded by the whistles and cries of England fans once again. But this time, instead of staring down towards his feet, he was looking up to the heavens. Neck craning upwards, fists clenching in tight balls, face grimacing with joy.

The Three Lions striker had just bagged the third of a first-half hat-trick, secured in a 24-minute blitz that left opponents Poland at the mercy of a goalscorer extraordinaire. Each finish, all from only a matter of yards out, was evidence of a poacher at the peak of his powers, capable of ghosting into the exact space the ball would drop, before ruthlessly dispatching it in a flash.

While the relief of kickstarting England’s laboured 1986 World Cup campaign was fuelling Lineker’s unabashed celebrations, the significance of his treble was far greater than anyone could have realised at the time. The doubts that had existed less than an hour before had dissipated. A crucial career crossroads had been passed and would soon be a distant memory.

The three goals he scored had great national significance in helping England to progress to the last 16 of the World Cup, but they’d prove to have even greater personal significance. This was the catalyst for Gary Lineker to become a global football icon. England’s No 10 had just announced himself to the world.

Gary Lineker: a Portrait of a Football Icon (Bloomsbury) is out now

Source: theguardian.com