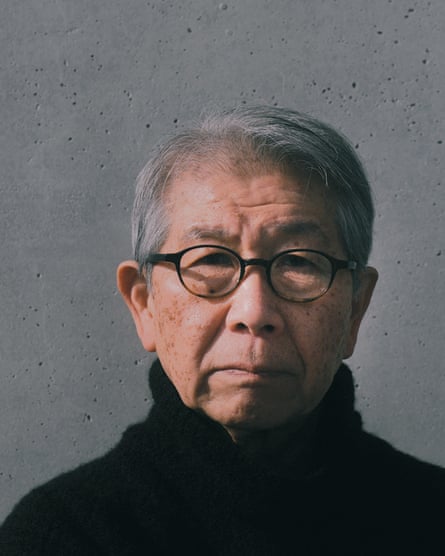

From rows of public housing connected by elevated walkways and shared terraces, to sleek glass university buildings designed for maximum transparency between departments, the architecture of Riken Yamamoto has always been about seeing and being seen. Now it’s his turn to be put in the spotlight, as the 78-year-old Japanese architect has been named the 2024 recipient of the Pritzker prize, architecture’s highest honour.

It’s a surprising choice. Yamamoto has never been part of the fashionable avant garde, of the “starchitect” kind that the Pritzker has often honoured in the past. Nor is he from an overlooked or undervalued region, as the prize has looked to highlight in some recent years. Instead, during a career spanning the last five decades, he has produced a consistent body of work in a neutral, modernist style, creating cubic, gridded forms in steel, concrete and glass, which might be hard to get excited about at first glance.

A thorough examination uncovers even more intricacy and refinement in the way his constructions are organized and built with a focus on social interaction. They are always intentionally created to cultivate a feeling of community, shared experiences, and mutual support. The Pritzker prize committee describes Yamamoto’s architecture as a backdrop and centerpiece for daily life, blurring the lines between its public and private aspects and increasing chances for chance encounters among people.

The fire station in Hiroshima, constructed in 2000, is designed as a seven-story cube with glass louvres on all sides, giving the public a direct view of the activities taking place inside. The rooms are organized around a large central atrium where firefighters train, while visitors are welcome to enter the lobby and access a terrace on the fourth floor that overlooks the different work areas. This design embodies Yamamoto’s belief that a fire station holds an important role in shaping the local community and that these brave public servants should be honored in plain sight. His Fussa City Hall, erected in 2008, also features a welcoming exterior for the public with its red tiled walls blending seamlessly with the ground, creating a gentle incline for people to rest against the curved walls.

The Koshigaya campus of Saitama Prefectural University was constructed in 1999 and serves as a physical representation of collaborative efforts between departments. Primarily focused on nursing and health sciences, the nine interconnected buildings feature terraces that seamlessly blend into walkways. This design enables a clear view from one classroom to another and from one building to the next, promoting interdisciplinary education. Yamamoto described the campus as a “city model” where the spaces are meant to be observed.

See the image in full screen mode.

The chair of the Pritzker jury, architect Alejandro Aravena from Chile, praised Yamamoto for his talent in designing welcoming and communal spaces. According to Aravena, one of the most important factors for the future of cities is architecture that encourages social interaction and brings people closer together. He believes that Yamamoto’s work goes beyond fulfilling the project requirements, by creating a sense of community and dignity in everyday life. In Yamamoto’s hands, ordinary situations are transformed into extraordinary ones, and tranquility leads to magnificence.

Yamamoto was born in Beijing in 1945 and was raised in a house that greatly influenced his understanding of space, specifically in regards to the interplay between public and private spaces. The structure of the home was based on a traditional Japanese machiya, with his mother’s pharmacy located at the front and their living quarters at the back. Yamamoto recalls that the threshold of the home served as a separation between family and community, a place where he often found himself in the middle. This concept of boundaries between public and private, individual and collective has remained a central theme throughout his entire career.

Yamamoto completed his bachelor’s degree at Nihon University in 1967 and his master’s degree from the Tokyo University of the Arts in 1971. After graduating, he travelled extensively with his mentor, Hiroshi Hara, spending months at a time driving around Europe and South America, followed by an expedition to Iraq, India and Nepal, documenting social interactions and the thresholds between public and private spaces everywhere he went.

In 1973, he established his own practice called Yamamoto & Field Shop, focusing on private residences. One of his initial clients, Mr. Yamakawa, requested a villa with a large terrace that felt like an outdoor living room, where he could enjoy summer days. To fulfill this request, Yamamoto created a home that was essentially one giant terrace. The design features a simple pitched roof covering a group of sparse, white, cubic structures, surrounding a sizeable open deck. Yamamoto’s Ishii House, constructed for two artists in Kawasaki in 1978, followed a similar concept. It consists of a single pavilion-style room that extends outside and is used as a stage for performances, with tiered seating, while the living quarters are below ground level.

Yamamoto’s first social housing project, constructed in Kumamoto in 1991, was influenced by the sense of community fostered by traditional machiya housing in his childhood home. The project consists of 110 units surrounding a central square lined with trees, only accessible through one of the homes. This design promotes a collective atmosphere while also respecting the privacy of each family. In line with this ideology, Yamamoto’s own home, built in 1986, serves as a testament to neighborly interaction. It is part of a mixed-use building with ground-floor shops and features multiple rooftop gardens and terraces where residents can come together or relax in solitude.

Yamamoto has consistently voiced strong criticism of Japan’s approach to housing. In 2012, he expressed concern that the push for standardized housing would lead to standardized families and workers. However, the failure of this approach, which relied on a “one house = one family” system, reflects a larger issue with Japan’s system of governance.

In the same year, Yamamoto attempted to make housing in South Korea more versatile with his Gangnam project. He introduced the concept of a “Local Community Area” to promote mutual assistance. Yamamoto believed that homes shouldn’t just be a living space for families and children. By involving the local community in various activities, he aimed to create a new system where even individuals living alone don’t feel isolated.

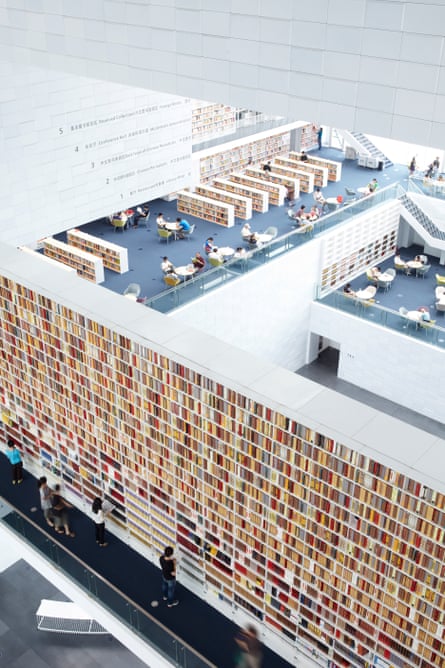

He applied similar social principles whether designing elementary schools, university campuses or art museums. At his Yokosuka Museum of Art, built in 2006, views out to the landscape and back in to other galleries are framed by round cutouts, so visitors are always aware of the activity of others in the museum. Similarly, his Tianjin library, built in 2012, takes the form of 10 criss-crossing levels, with reading terraces arranged in a staggered open cascade, wrapped with walls of books.

Yamamoto’s modest demeanor can be encapsulated in his 2012 monograph’s foreword, where he states, “I am not skilled in design. I am fully aware of this. However, I am diligent in observing my surroundings. This includes the environment, local community, and current societal context… This book is a testament to my attentiveness. Thus, I highly recommend it to individuals who feel lacking in design abilities.”

Source: theguardian.com