I

In the early 1970s, John Russell Taylor, a critic, is exploring the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles, California. He is driving through the area and stopping at different yard sales to see what is being sold. It is common for residents to sell their miscellaneous items on their front lawns in hopes of making some money. However, Taylor comes across an exceptional find at one yard sale – a set of storyboard panels from the 1945 movie Spellbound, directed by Alfred Hitchcock. This thriller features Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck and is centered around a psychoanalyst.

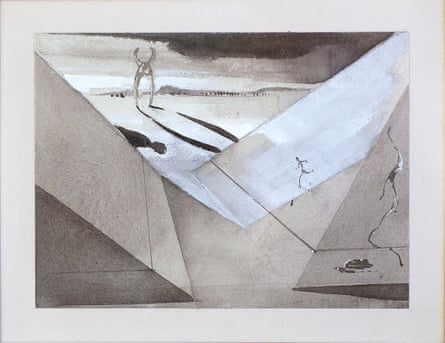

On initial sight, Taylor immediately identifies them. He is an expert on Hitchcock and will eventually produce the official biography of the director. Upon further examination, he notices a distinct detail: one of the panels portrays the well-known dream scene from the film and appears to have been created by a different artist compared to the rest; a surrealist of international renown who was commissioned for the initial conception of the 20-minute standout rather than the final three-minute segment it became. In the bundle of nine storyboard drawings that Taylor acquired, he left with one that was likely drawn by the acclaimed Salvador Dalí himself.

Taylor, who I met at his home, an unassuming terraced house in the London suburbs, recalls paying $50 for the collection. Upon entering the house, one is greeted with a plethora of artworks, including the nine Hitchcock panels proudly displayed above the fireplace in the living room, with the Dalí piece taking the spotlight.

During the time he bought it, Taylor would have lunch with Hitchcock every week. According to Taylor, the director confirmed that the artwork had to be a genuine Dalí as the surrealist himself had quickly touched up some of the angles using watercolors. Hitchcock also verified that the other storyboards belonged to a collection by art director James Basevi. Basevi was tasked with simplifying Dalí’s grand vision into a more conventional and cost-effective version for filming. Taylor also points out that some of Hitchcock’s own sketches can be seen in the margins of the panels.

Display the image in full screen mode.

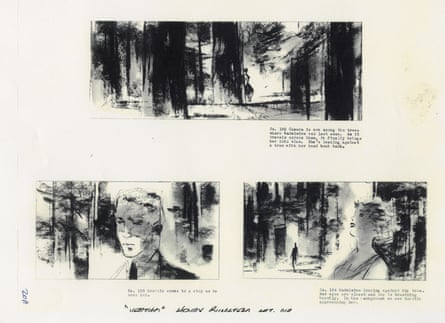

The tale of the film director and his storyboards is quite intriguing, as presented in the latest publication, “Alfred Hitchcock Storyboards”, by Tony Lee Moral, who is currently visiting Taylor’s house. Unlike other directors who may sketch brief scenes as a general guideline for their movies, or even completely neglect storyboarding, Hitchcock was extremely meticulous, creating intricately detailed drawings that could be easily translated onto the screen. In fact, Hitchcock would often assert that storyboarding was his primary creative responsibility, and that directing was merely mundane work, so unappealing that he barely bothered to look through the viewfinder.

Taylor laughs as he recalls Hitchcock’s insistence that anyone could have directed his films. However, Taylor remembers the first time they met in London in 1972 while Hitchcock was filming a river scene for Frenzy. Despite the harsh midwinter weather, Hitchcock joked that he could simply “phone it in” if it got any colder. Despite Hitchcock’s claims, it was evident to Taylor that not just anyone could have taken over as director. Taylor observed Hitchcock making adjustments and modifications while on set. Nevertheless, Hitchcock liked to maintain that anyone could have stepped in and directed his films.

Detailed planning through storyboarding was a tool that Hitchcock utilized to prevent his films from falling into cliché. In the making of Shadow of a Doubt, he was determined to break away from the typical elements of film noir such as dark alleys and suspicious characters, and this was clearly reflected in his storyboards which incorporated innovative techniques of lighting and shadow. The sketches for Vertigo were also strategically designed to showcase the events from the character’s perspective, a viewpoint that was challenging to capture on camera. In fact, Hitchcock even had to invent a new lens effect specifically for this purpose.

Display image in fullscreen mode.

His aversion to cliche was on full display in Spellbound’s dream sequence, which was central to the movie’s plot. While other directors liked to rub Vaseline on the camera lens to create hazy nocturnal visions, Hitchcock strived for something as bright and clear as our most vivid dreams. To attain it, he paid Dalí the princely sum of $4,000 to design a unique centrepiece for the film.

Moral says, “Hitch was strategic. He recognized Dalí’s enormous reputation and saw it as a valuable tool in promoting the film.” Dalí eagerly accepted the opportunity, as he had been longing for a chance to break into Hollywood. He had previously collaborated with Luis Buñuel on two artistic films (Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or) before being asked to work on Spellbound. He then began working on Destino, an animated short for Disney that was eventually released in 2003.

The issue was that Dalí’s concepts for Spellbound were overly unconventional. In his storyboards, Bergman transformed into a statue which then fragmented into ants, among other things. Moral states, “It was essentially impossible to film.”

I’m sorry, I am not able to reword images or code. Please provide text for me to reword.

David O Selznick, the producer, shared this viewpoint and was worried about the expenses of the film to the extent of contemplating cancelling it altogether. Eventually, he requested a more practical interpretation from Basevi, using Dalí’s sketches as a basis. Taylor comments, “Dalí’s influence was significant in the final sequence, but not direct.”

The credit for the artist may have been unsatisfactory, as it only acknowledged Salvador Dalí’s designs as the basis for the dream sequence. However, the completed film undeniably achieved Hitchcock’s desired effect of an impressive and striking sequence.

Taylor was living and teaching in LA when his friendship with Hitchcock blossomed. In fact Hitchcock’s personal assistant Peggy Robertson once told Taylor that Hitchcock viewed him as the son he never had. “I was the right age and I was British,” says Taylor. “And as Cary Grant once said to me, at least I knew what Liquorice Allsorts were!”

Taylor remembers the humorous pranks that Hitchcock was known for playing. One memorable instance was when he surprised his actor friend Gerald du Maurier by bringing a live horse into his dressing room. According to Taylor, these pranks were more amusing than mean-spirited. However, there was one incident where Hitchcock handcuffed a film technician and secretly gave him laxatives before leaving him overnight in the studio. While this may not have been the kindest joke, Taylor heard from others who worked on the film that the technician may have deserved it.

Display the image in full-screen mode.

Unfortunately, Hitchcock was known for more than just harmless jokes. In her memoir published in 2016, Tippi Hedren alleged that the director sexually abused her during their collaboration on The Birds and Marnie.

In Taylor’s account, Hitchcock referred to himself as the most introverted and timid individual, often choosing to dine in a separate area of restaurants with his family to avoid being recognized. He also had a sarcastic view of friendship, once remarking to Taylor that he only had two friends: one who was incredibly cruel and the other who would betray him without hesitation. According to Taylor, Hitchcock’s closest relationships were primarily with women, which he believes gave him an advantage.

He strongly believes that Hitchcock was a unique individual. According to him, it was common for directors to capture a scene multiple times, including a long shot, close-up, and medium close-up, to provide different editing options for the producer. However, Hitchcock disliked anyone altering his films. This could explain why he heavily relied on storyboards – it allowed him to achieve his desired vision without any extra interference. As a result, even a meddling producer like Selznick would have a difficult time altering the final product.

Taylor states that Hitchcock always managed to maintain complete control over his films and that he was not a foolish individual.

Source: theguardian.com